PictureTime: The Balloon And The Box Office

How Sushil Chaudhary used inflatable cinema theatres to build a backroad to Bollywood, bringing the magic of movies to the Middle of India

Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 395 new subscribers who've joined Tigerfeathers since our last piece.

Last time out we published a deep dive on the upcoming IPO of Urban Company, a start up that almost 100% of our readers in India will be familiar with.

This time around we're featuring an interview with the founder of a company that closer to 0% of you will have heard of.

Next time we’re aiming for exactly 50% awareness, then 25%, then 75%, because nothing says ‘professional editorial strategy’ like a random sequence of brand recognition.

Subscribe below for more hot tips on how to build an Internet-first media company👇

This edition of Tigerfeathers is presented by…Dhan

Five years ago, if you were a serious trader or long-term investor in India, you likely felt that the tools at your disposal weren’t keeping up with your requirements. That's exactly what Pravin Jadhav noticed when he was building India's largest mutual fund investment platforms from the ground up over the latter half of the 2010s.

He left his last role in 2020 as one of the most pedigreed fintech product specialists in the country, deciding to focus on a single question for his next venture, namely - "Why had India’s brokers stopped innovating?" That led to the founding of Raise Financial Services and their flagship product, Dhan.

Unlike other platforms chasing first-time speculators, Dhan builds for experienced traders who need speed and precision, and thoughtful long-term investors focused on compounding wealth. That translates to advanced charting with TradingView integration, lightning-fast execution, and real time portfolio analytics to help users make better decisions.

Outside of their product features, what makes the company different is their approach. The team is constantly on the road, travelling across 15+ cities talking to traders and investors, running an active online community, and shipping updates based on real feedback rather than assumptions. Every feature comes from a real problem.

Today over 10 lakh traders and investors use Dhan to manage their capital and make better investment decisions. As more Indian enter the country’s capital markets over the coming decade, Dhan wants to be the platform powering their confidence.

If you’re looking to level up your investing toolset, consider joining the Dhan community here, or check out the platform below:

And if you're interested in sponsoring a future edition of Tigerfeathers, hit us up on Twitter/LinkedIn or by replying to this email. With that, let’s get to it.

Three years ago we heard about a company that was pinning its post-pandemic hopes of survival on the performance of S. S. Rajamouli’s barnburner of a film RRR.

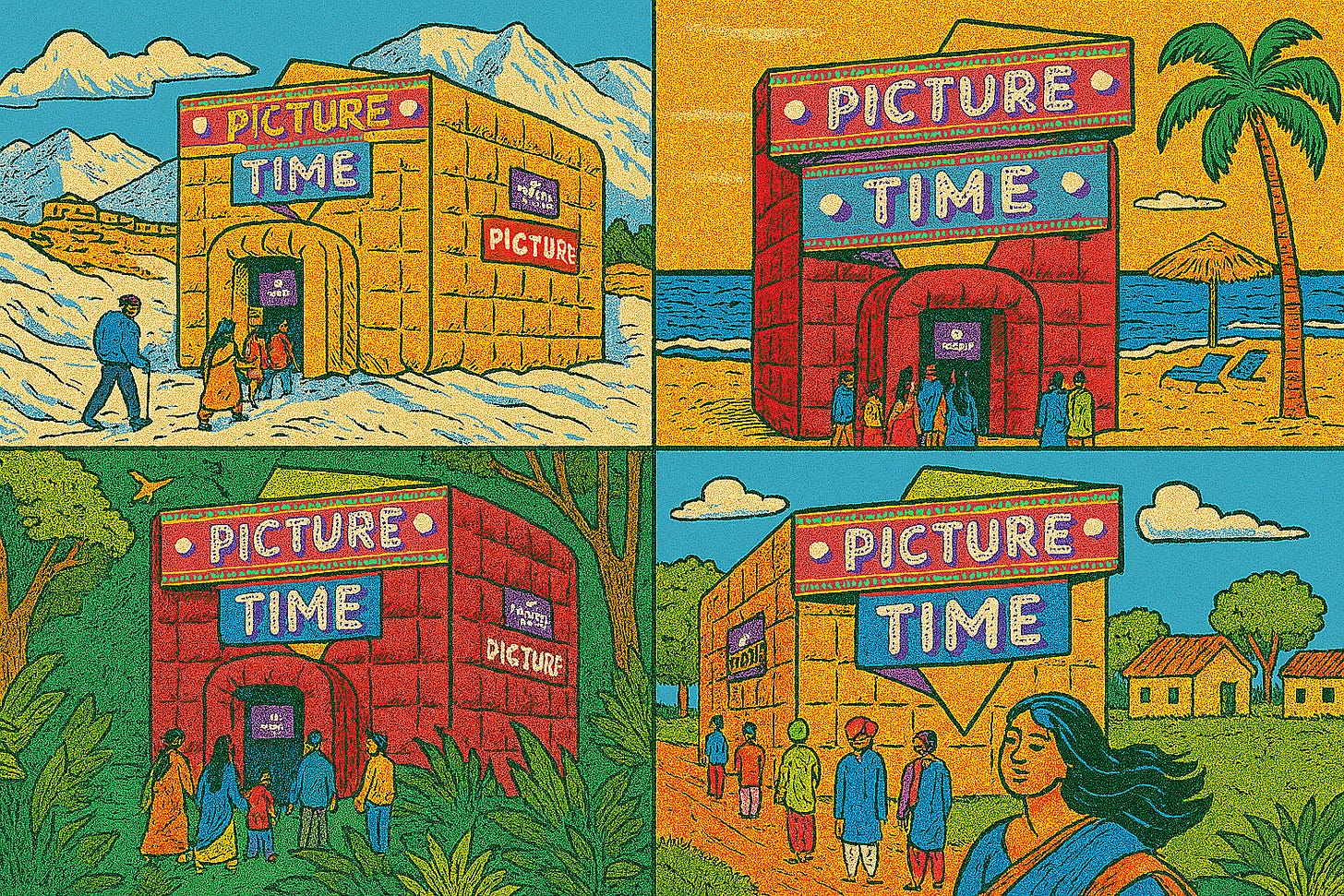

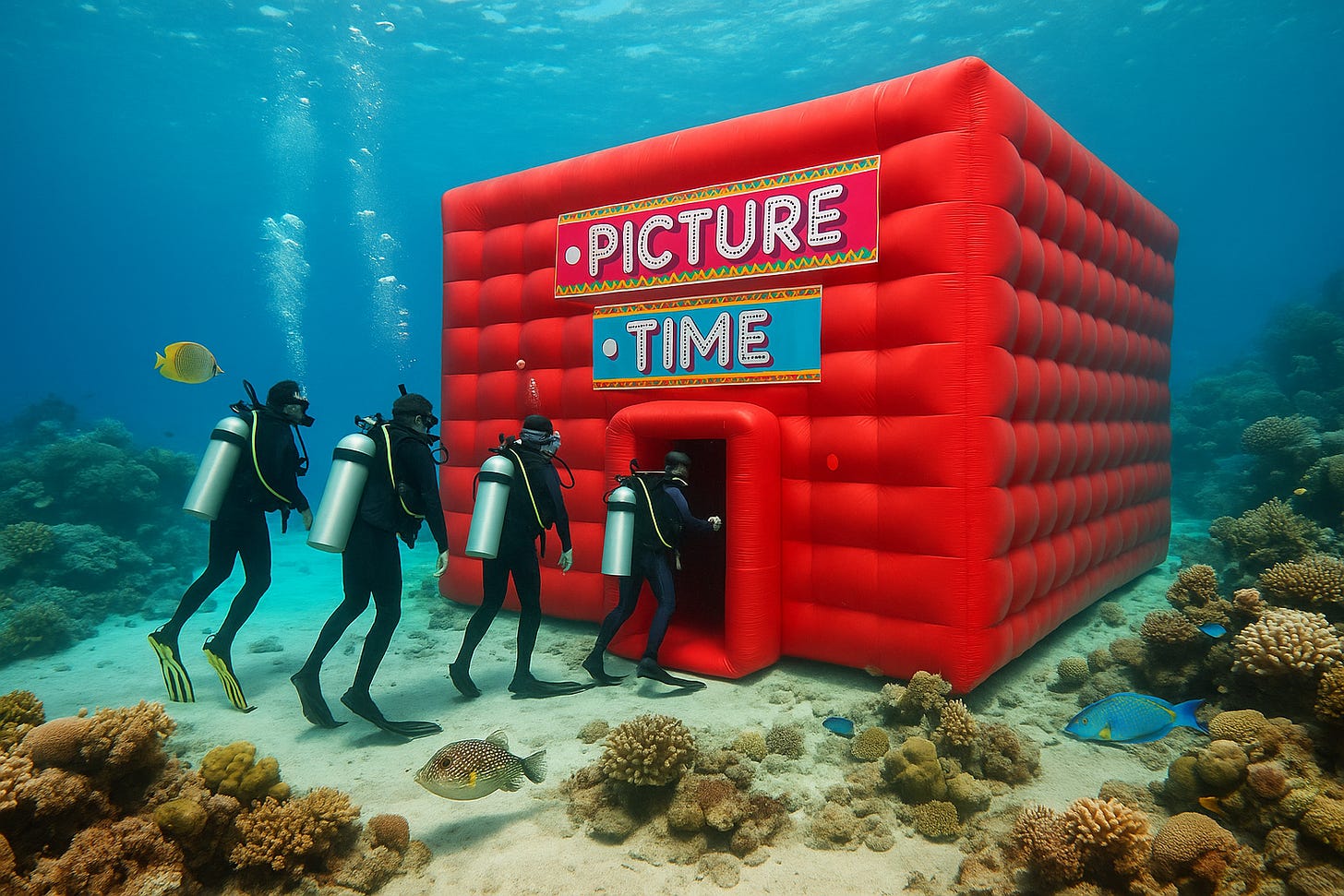

This company - PictureTime - was in the business of making and operating an entirely unique set of products - inflatable movie theatres.

By 2022 they were more than seven years into a journey that began with a goal to transport the magic of cinema into the hinterlands of India.

It was founded by a veteran of the early-2000s Indian IT services wave - Sushil Chaudhary - who realised that India’s chronic lack of theatre screens outside of its metros was strangling the performance and potential of its film industry, that should have been rivalling Hollywood in terms of global scale and soft power.

Sushil, an unabashed cinephile, started the company because he believes that after people’s basic needs are satisfied, everyone should have a fundamental right to art, beauty, and, most importantly - cinema.

If you’ve raised your eyebrows at any point in the last five sentences, it should come as no surprise that PictureTime has been on our Google Doc of ‘Indian companies to cover’ for a long time. A few weeks ago it became apparent that it was the right time to bump it up the list. Why now? We’ll have to briefly rewind back to the first week of May 2025.

From the 1st to the 4th of May this year, Mumbai played host to the inaugural edition of the World Audio Visual and Entertainment Summit (WAVES). Organised by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (Government of India), WAVES was intended to be a landmark global event that cemented India’s arrival as an entertainment and media juggernaut. It brought together the heavy hitters, the usual suspects and the upstarts making headway in different corners of the country’s creative universe. We assume the invite for the ‘Tigerfeathers Delegation’ must have gotten lost in the mail.

Anyway, as perhaps the most visible and formidable bastion of the country’s storytelling prowess, Indian Cinema was a major theme at WAVES. In particular, considerable time was spent trying to diagnose the confounding current state of Bollywood.

Depending on your penchant for hyperbole, India’s Hindi film industry is either in a rut, a reset, or a recession. A quick Google search will tell you that Bollywood is stuck in a malaise of lacklustre scripts, a sluggish box office, dwindling occupancy rates, a loss of market share to other regional powerhouses, and economic pressures provoked by the rise of AI and OTT.

You could spend a lot of time debating the various causes and effects at play here, but at WAVES, two of Bollywood’s silver-screen titans both attributed this to the same cause that Sushil has been championing for over a decade.

Shah Rukh Khan, responding to Karan Johar’s question on how Bollywood can be ‘saved’ said “I still believe the call of the day is simpler, cheaper theatres in smaller towns and cities so that we can showcase Indian films in whichever language to a larger majority of Indians for cheaper rates. Otherwise, it's becoming very expensive, only in big towns”.

Later adding to the chorus, sitting alongside Ajay Bijli (CEO of PVR INOX), Aamir Khan declared that “…we need to have a lot more theatres in India and theatres of different kinds. There are districts and vast areas in the country which don't have a single theatre. I feel that whatever issues we have faced over the decades are just about having more screens. And according to me, that is what we should be investing in. India has huge potential, but that can only be realised when you have more screens across the country. If you don't, then people won't watch the films.”

Both statements would accurately fill in as shorthand for the PictureTime business case. In fact, Sushil himself was later asked for a response during his own panel titled ‘Decline in the Theatrical Industry and Sparse Cinema Distribution’, a panel that was relatively devoid of starpower, so much so that not a single news outlet bothered to upload it online, and I had to ask a friend at Netflix to fish it out of their Slack channel.

“I was happy to hear what Shah Rukh said regarding the need for more cinemas and cheaper tickets,” he responded. “Cinema is all about affordability, accessibility, and entertainment. After roti, kapda, aur makaan, cinema is a basic need. When we build our cinemas, the focus is on keeping the capital cost under Rs. 1 crore and the operational costs under Rs. 2 lakhs.”

From what we understand, all three comments reverberated in India’s film circles long after WAVES. Given the encouraging re-entry of PictureTime into the mainstream cinematic discourse - and the apparent arrival of a clear ‘Why Now?’ for his solution - we reached out to Sushil and asked if he would sit down with us for an interview. He was kind enough to give us three hours of his time a couple of weeks ago, taking us through not just his own journey and product, but the history of film in India, the state of play in the industry today, and how his company is trying to help the cause.

It’s turned into one of our favourite stories, because:

Like many of our most compelling Tigerfeathers topics, this one is a little bit further out on the ‘Wait, what?’ curve - like asteroid mining or temples on your phone;

It allowed us to learn about the past, present, and future of an industry we had no clue about - cinema🍿;

And, as you’ll find out, it’s one of the most fascinating and curiously under-covered Indian ‘start up’ stories - stranger because it involves a genuinely innovative technical product that’s been built around a clever business case, one that’s solving a pernicious problem that’s confounded one of our most celebrated industries for several decades.

If we’re being honest with ourselves, we should have probably reached out sooner. But as Sushil told us, after a decade of building, pivoting, and engineering, PictureTime is finally ready for real scale - bringing movies to the "other 98% of India" that multiplexes forgot. In other words, it was the perfect time to tell their story.

Anyway, enough blathering. We hope you - like us - will enjoy this conversation with PictureTime’s Founder and CEO, Sushil Chaudhary.

I] Origin

Perhaps a simple one to set the table here – how does someone get into the business of setting up inflatable cinema halls in remote parts of India? What were the personal or professional steps that led you to the idea?

So, before starting PictureTime, I was running a tech services company called Mann-India Technologies for a long time. I had co-founded the company with three other friends in the year 2000. Two of them were my batchmates at the National Institute of Technology, Tiruchirappalli, where I had gone to college to study engineering. At the time the Indian IT services wave was picking up steam in the West. But most of our peers were focused on Europe and the US. We decided to focus on South and Latin America, where we were able to capitalise on an early mover advantage.

That experience was magical. We did a lot of pioneering work in the region helping local enterprises and governments grapple with the Internet and computers and software for the first time. Our model was to establish local software development hubs for the region and to really embed ourselves in the local economy and culture. A bit of historical trivia is that we had the distinction of building Latin America’s first USSD-based mobile payments system out of Panama.

Anyway, I spent several years living in Latin America too. I spent significant time in Colombia, Peru, Venezuela, Panama, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and a few other places because our operations were spread across nine countries. I loved it, but being away from home, the thing I used to miss most was Indian films. I’m an unabashed cinephile, and I love Indian films more than anything.

The thing was that in our little community, we always split into two camps whenever the topic of Indian cinema was brought up. One group would always turn their noses up at Indian films. They would say ‘We have access to Hollywood movies, Western movies - why waste your time on the same reductive stories, the same buffoonery, the same romantic plots?’. I never agreed with that.

Sure, parts of Indian cinema are mass-y. But to me there’s so much more than just the stereotypical Bollywood blockbusters. I grew up on the films of Hrishikesh Mukherji and Satyajit Ray - real, respected artists the world over. I never agreed with that perception. And to be honest, I was always curious about why Western movies were known the world over, but so much of great Indian cinema was ignored not just by the rest of the world, but by Indians too.

How did that curiosity lead to PictureTime?

When I left Mann-India around 2011-2012, I was thinking about what to do next. I didn’t want to just jump back into tech, I wanted to do something I was passionate about. My interest kept coming back to films, and particularly around digging more into this perception that India was good at making entertaining films, but not necessarily great films. On the other side of things, I was curious about why Hollywood had become “Hollywood”, attracting this reverence as the global leader of cinema. So I started doing some research, first on my own, then with a team of analysts that I hired. A few things stuck out to us.

The first was that India is neither bad at cinema, nor new to it. If your readers don’t mind, maybe I can give a brief background about some of the major milestones in the history of film in India to set some context.

I think our readers are used to it. Please go for it.

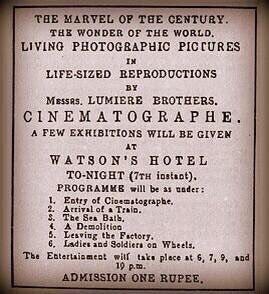

So the first film that was ever screened in India was in 1896 by the Lumière Brothers - these two French pioneers who had invented the cinematograph a year earlier. This was the technology of ‘motion pictures’. They screened a series of short films at the Watson Hotel in Mumbai, showing scenes like workers leaving a factory and a train pulling into a station. These were black and white, soundless clips that lasted less than a minute each but absolutely captivated Indian audiences.

Seventeen years later, in 1913, came India's first full-length feature film - Raja Harishchandra. This was directed and produced by Dadasaheb Phalke, now known as the 'Father of Indian Cinema'. This 40-minute silent film was based on the legend from Hindu mythology about a noble king who sacrifices his kingdom, wife, and children to honour a promise to a sage. Phalke scripted, produced, directed, and distributed the film himself, and it was a huge commercial success that laid the foundation for India's film industry.

The casting call published in various newspapers said:

"Wanted actors, carpenters, washermen, barbers and painters. Bipeds who are drunkards, loafers or ugly should not bother to apply for actor. It would do if those who are handsome and without physical defect are dumb. Artistes must be good actors. Those who are given to immoral living or have ungainly looks or manners should not take pains to visit."

Interestingly, because of social taboos around women acting professionally back then, Phalke had to cast men in all the female roles. In fact, the film business as a whole was considered taboo, so Phalke had to advise his cast and crew to tell people they were employed in a factory owned by a man named Harishchandra.

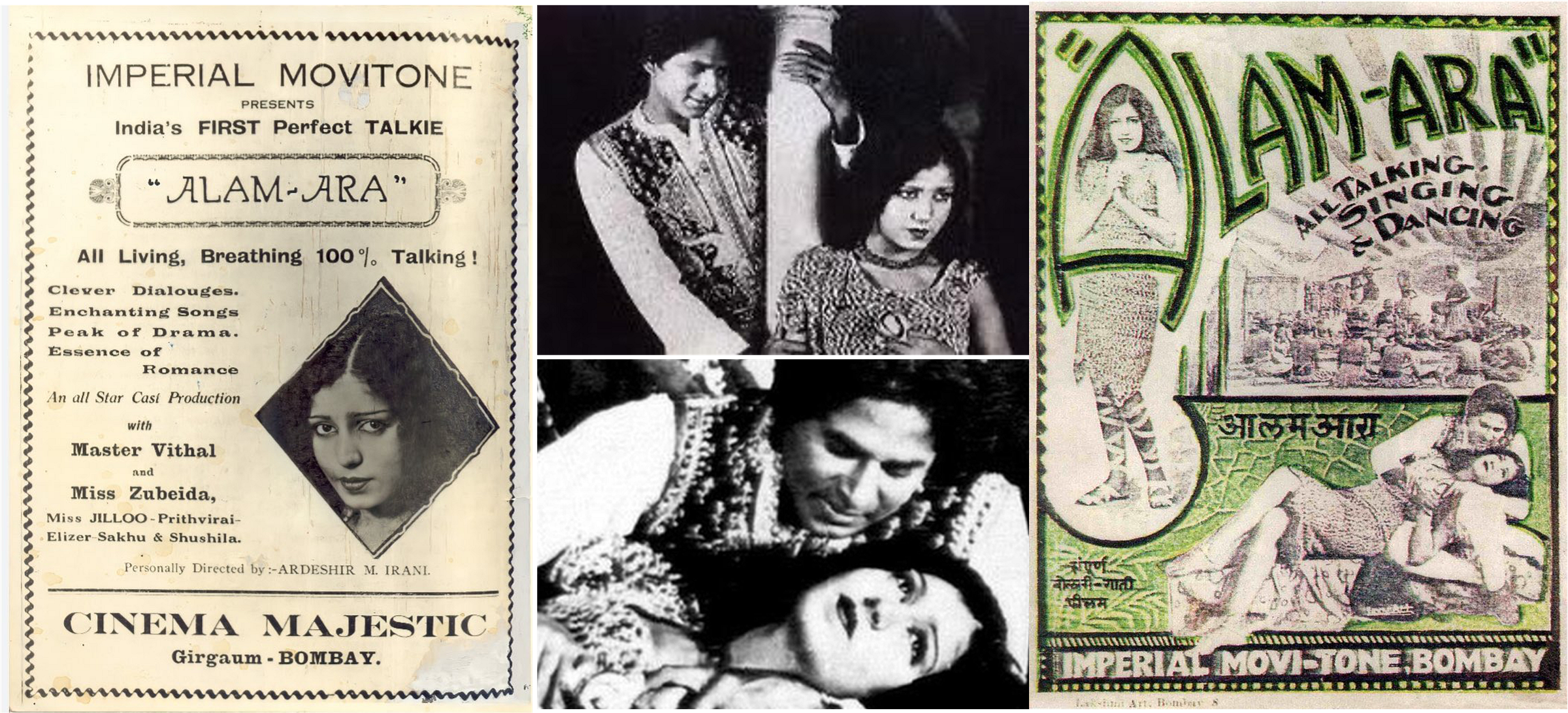

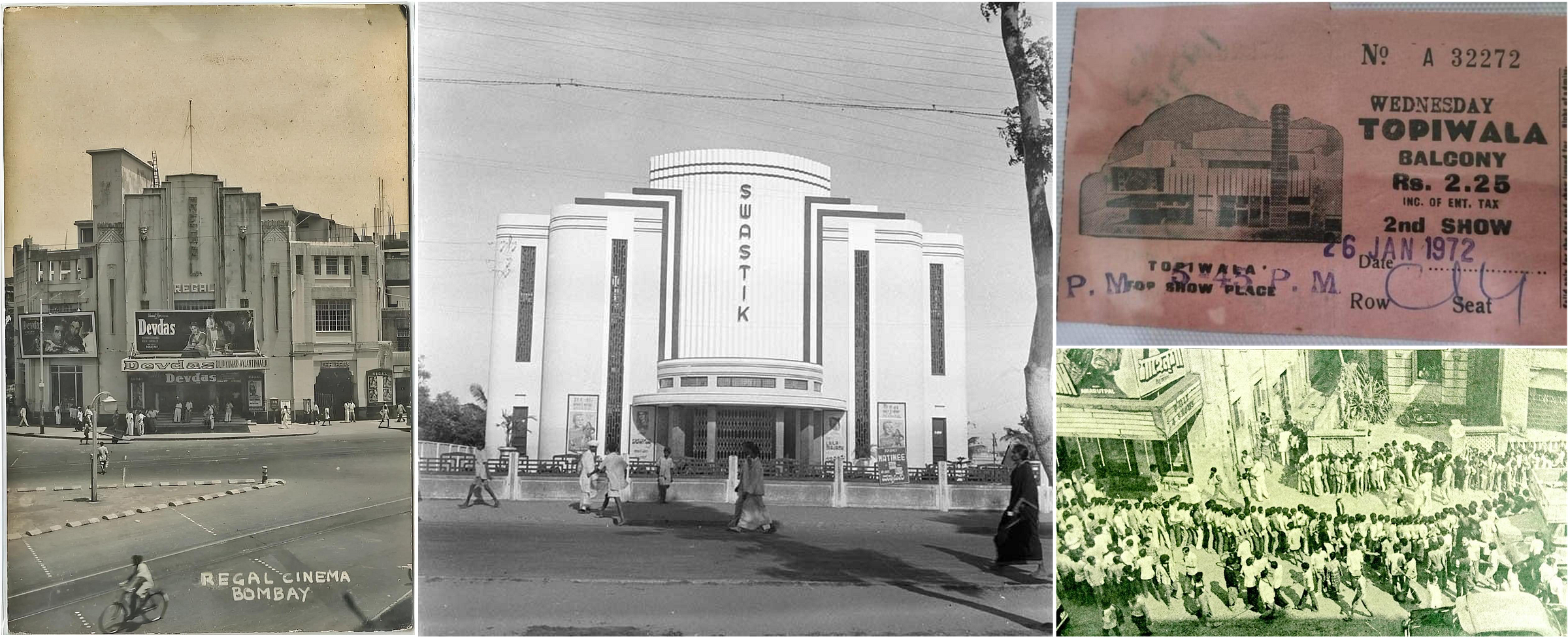

Then in 1931 we had Alam Ara, directed by Ardeshir Irani - India's first 'talkie' or sound film. It was released at Majestic Cinema in Bombay, and caused such a sensation that police had to be called to manage the crowds, and tickets that normally cost 4 annas were selling for 4-5 rupees in the black market.

By this time lots of film-loving pockets were emerging all over India, particularly in the South. People were importing equipment to set up film studios, others were setting up single screen theatres as small business ventures. It meant the rise of regional cinema culture that had its own individual flavours.

By the end of the 1930s, Indian cinema had tasted global appreciation too. Regional language films like Sati Savitri (1933), Seeta (1934), and Sant Tukaram (1936) had been screened at international film festivals. The latter - a Marathi film - was judged as one of the three best films of the year at the Venice Film Festival in 1937. It broke box office records at the time and was still playing in Indian theatres one year after release. These kinds of films set the template for ‘devotional’ films that would become common in the culture of Indian entertainment.

My point is that India’s foray into the world of film goes back more than a hundred years. By Independence, it was already a popular form of entertainment, especially so because tickets were very affordable. After 1947, things really took off. We entered the ‘Golden Age’ of Indian cinema, roughly the 1950s and 1960s, where, by some accounts, we became the second largest film industry in the world by revenue. The major change post Independence was the emergence of Bollywood - i.e. Hindi-language films. The Indian film industry in many ways became remade in the image of Bollywood because the language was more accessible across different parts of the country.

Many of the biggest stars of this period - like Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor, Dev Anand - and many other important directors, cinematographers and writers migrated to Mumbai as a direct outcome of Partition, to escape the turmoil of the North-West. They hailed from places like Punjab, Peshawar, and Lahore, which meant that much of post-1947 cinema was a reflection of the sensibilities of North India. Many of these guys became international superstars, in places like the Soviet Union, China, America etc.

The term ‘soft power’ wasn’t popular then, but it is inarguable that the image of India in the 20th century - via its most popular films - was a reflection of Bollywood, which was in turn shaped by the values and ethos of Punjabi culture. [Bollywood is a portmanteau of Bombay and Hollywood. It became the home base of Indian film post Independence].

This period is when cinema became a real binding force. This is when the ‘Masala’ style of films - that combined song, dance, romance, action etc, building upon Indian traditions of natya (drama) nritya (pantomime) and nrrita (pure dance) - became heavily associated with Indian films and film culture, as India became more confident in expressing its traditions.

On the other side, you had this Parallel Cinema movement that was also emerging in the 1950s. This was led primarily by Bengali filmmakers like Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, and Mrinal Sen. This movement rejected the song-and-dance spectacle of mainstream cinema in favour of more ‘serious’ content. It was based on realism and social commentary, and pulled heavily from contemporary Indian literature. Films like Panther Panchali, Malliswari and Mother India were genuinely pioneering. They received multiple international awards and were greatly appreciated by foreign audiences. It was almost as if India had split its cinematic identity in two - one face for the masses and export of cultural soft power, another for artistic credibility and intellectual discourse. In fact we would have probably won some Oscars along the way if we had a stronger lobby (and if we didn’t always send our submissions in late).

This was all new information for me, as I’m sure it was for a lot of our readers. We appreciate the historical detour. How did this research tie back in to your original question?

So from my initial phase of research, the first key realisation that emerged for me was that India was not only capable, but prolific when it came to making world-class films. Even today Indian films are well represented and well received by critics at all the international film festivals. There’s no shortage of independent auteurs in this country.

If you are comparing the abilities and techniques of our filmmakers against their Western counterparts, we are neck and neck with them. However, the thing that stuck out to me as the main difference between India and America, which was at the root of why Hollywood had become “Hollywood”, was commercialisation. When it came to maximising the reach and revenue of their films, there was no comparison. They were miles ahead.

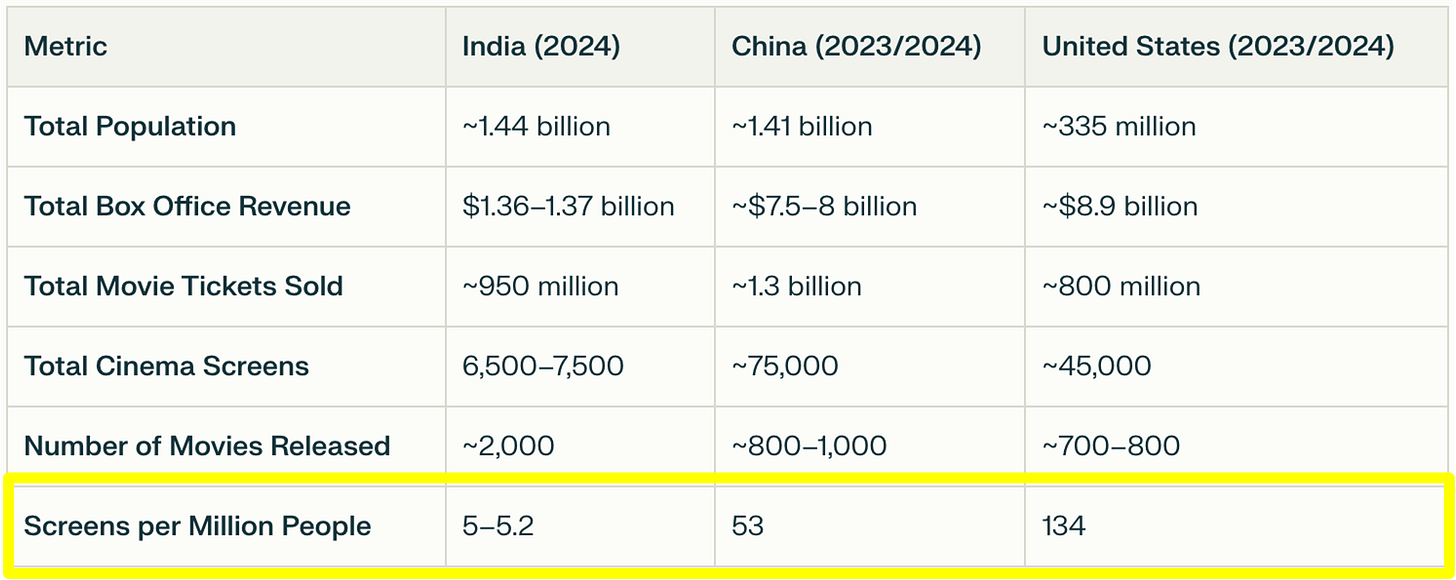

For example, when I was doing my research in the early 2010s, I found that India’s film industry brought in roughly 1/5th the revenue of the American film industry, and this was with thrice the number of movies produced (~2000 vs ~700), and with almost 5x the total population (~300 million vs ~1.3 billion). In fact, this was even worse in the early 2000s, where the American box office was closer to 10-15x bigger than India’s. That felt odd to me. So I started digging further.

A few factors popped out for why that’s the case:

1. Industry Status

- As big and important as film is to India, from a commercial perspective it was basically a cottage industry till relatively recently. There was no regulatory framework, no access to government benefits or subsidiaries. Films weren't given formal ‘industry status’ until 1998, which meant that for the first 75+ years of Indian cinema, filmmakers and producers couldn't access any institutional financing. This forced the sector to rely on informal and illegitimate funding sources, notoriously from Mumbai's underworld, which was a shadow presence in the early days of Bollywood.

- The Industrial Development Bank of India only set up the country's first major film fund in 2002. Compare this to Hollywood, which offered studios access to financing systems and formal capital markets from decades earlier. The result was that we never had the business infrastructure to scale, market, and distribute our films. The industry was mostly a closed group, family-run affair with a few big families dominating each territory and vertical.

2. Industry Dynamics

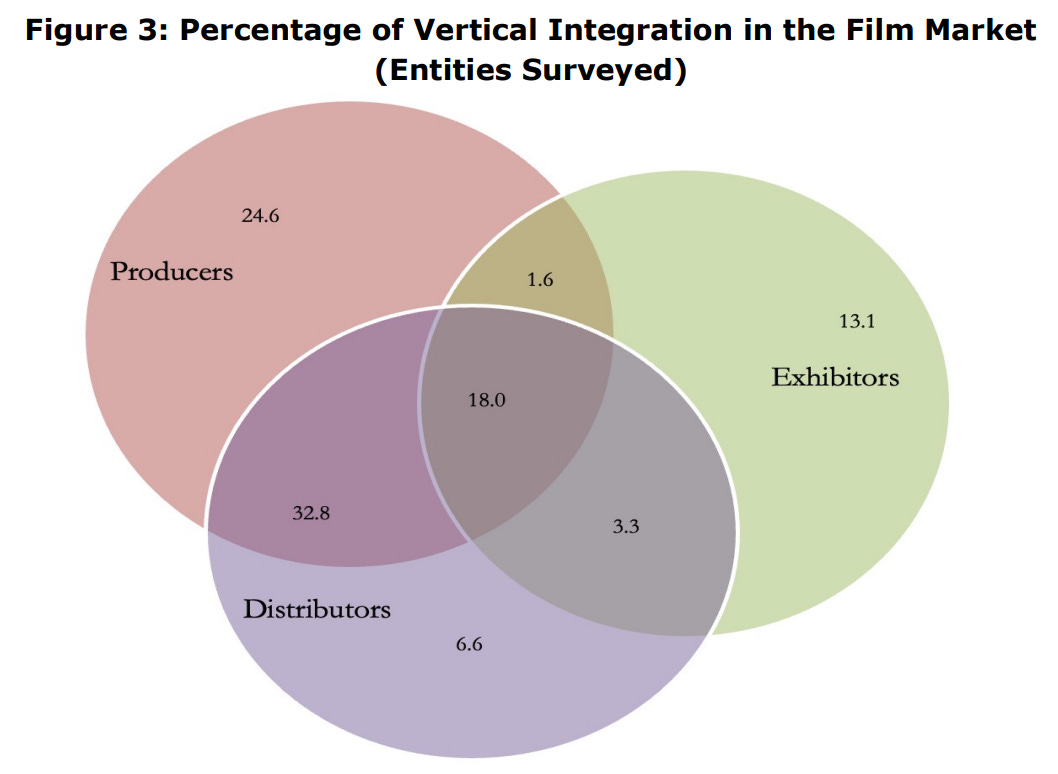

- The other major problem was the industry's distribution system, which was completely opaque and anti-competitive. The value chain has three main entities: Producers (like Yash Raj Films or Dharma Productions) who make films, Distributors (like Eros International or AA Films) who buy territorial rights, and then Exhibitors (like PVR INOX, Cinepolis India, and various single screen operators) who actually run the theatres and buy the rights to exhibit movies from Distributors. In the South it’s common to see companies vertically integrate across more than one role, but it’s relatively rare in Bollywood.

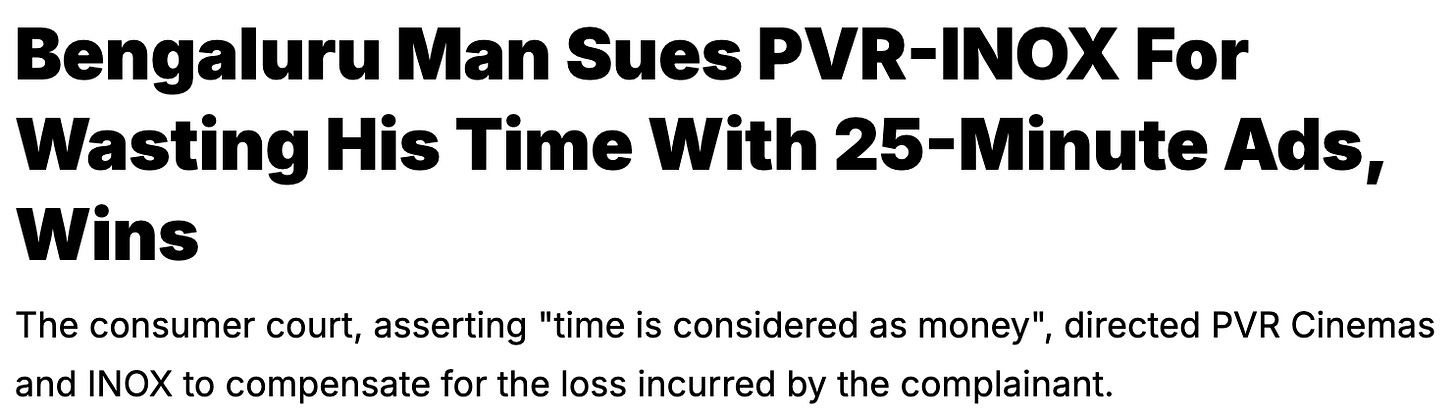

- Over time, distributors have consolidated into powerful cartels who essentially extort smaller exhibitors. For example, if you want the next Shah Rukh Khan blockbuster, the distributor will force you to also take three of their mediocre films as a bundle and commit to running them for minimum of two weeks each - even if they're disasters. Small single-screen operators get the worst treatment. They'll be told they can only get the big film in the third week, after all the multiplexes have had their run, and they'll pay a higher licensing fee for the privilege. Meanwhile, multiplexes get first-day-first-show rights and better revenue-sharing terms because they have more negotiating power. Sometimes the price is so high, or the audience response so poor, that exhibitors have to play excessive amounts of ads to make up the amount, which ruins the experience for everyone.

- This system made some sense in the old print days - like in the time when Sholay released in 1975, there were literally only 100 physical film prints made initially because these were expensive to produce and transport. These prints would travel from tier-1 cities to tier-2, then tier-3 towns over months or years, which is why the film ran for five years straight. The limited supply created natural scarcity and sustained buzz, especially when there wasn’t much television or OTT alternatives. But we're in the digital age now, where you can release simultaneously across thousands of screens with zero additional cost, yet distributors still operate like it's 1975. The result is that despite India producing almost 2,000 films annually, only about 200-300 get any meaningful theatrical release. The rest die in distribution limbo because they can't afford the minimum guarantees or don't have the right connections. A single screen in Bihar might only open for 7-8 weeks a year when big star films come out, because that's all they can access through this antiquated system.

3. License Raj

- The other major issue was with India’s regulatory framework for cinema (or rather the lack of one). Cinema falls under state jurisdiction, not central government, which means that each state has its own rules. Some states like Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh had developed relatively business-friendly policies because they valued cinema as part of the cultural fabric, but others like Uttar Pradesh were still operating under legal frameworks from the 1970s and 80s with no meaningful updates.

- The most damaging aspect was price controls. While both the Central censor board and the state governments exert control over what can be shown - state governments in many cases dictate how much theatres can charge for tickets. Even today, Tamil Nadu has a strict price cap for multiplex tickets (~₹200), and various other Southern states have similar restrictions. Of course, this is great for protecting the cinema culture in India, but for exhibitors [theatre operators], this created an impossible equation: you needed 70+ approvals and licenses to set up a cinema hall, a process that could take 3+ years, but then you couldn't set prices high enough to recover your investment.

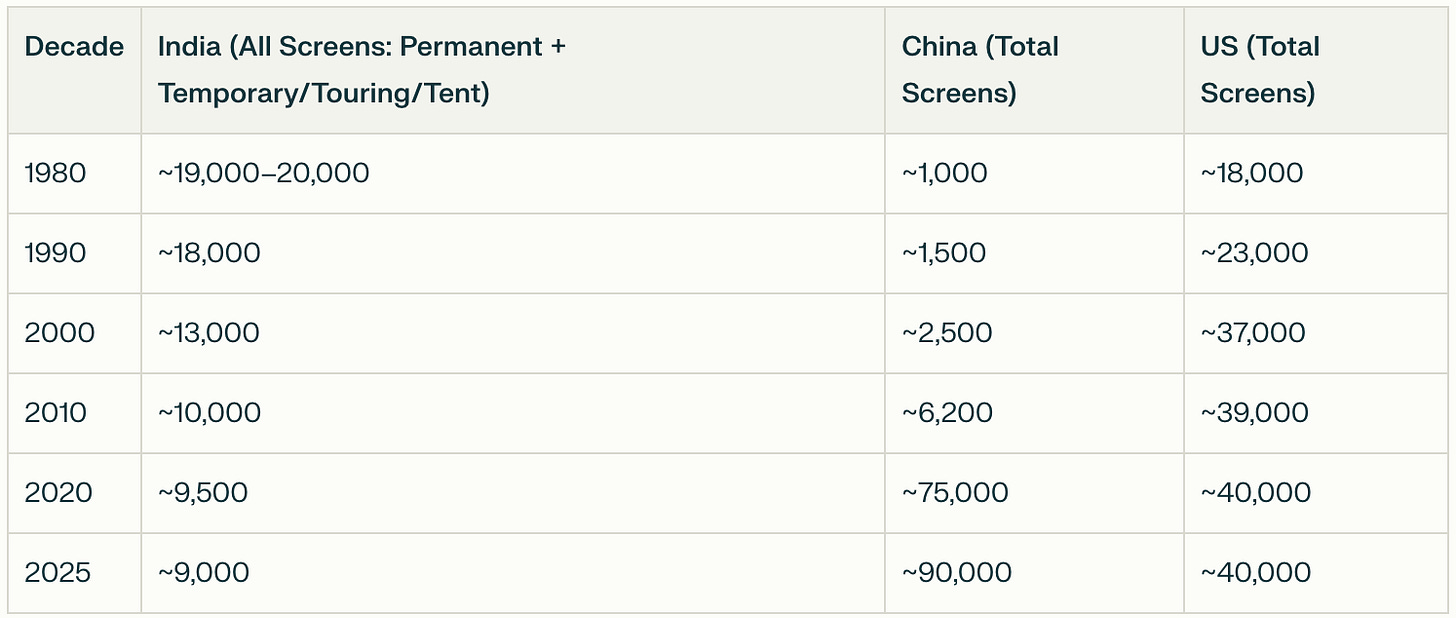

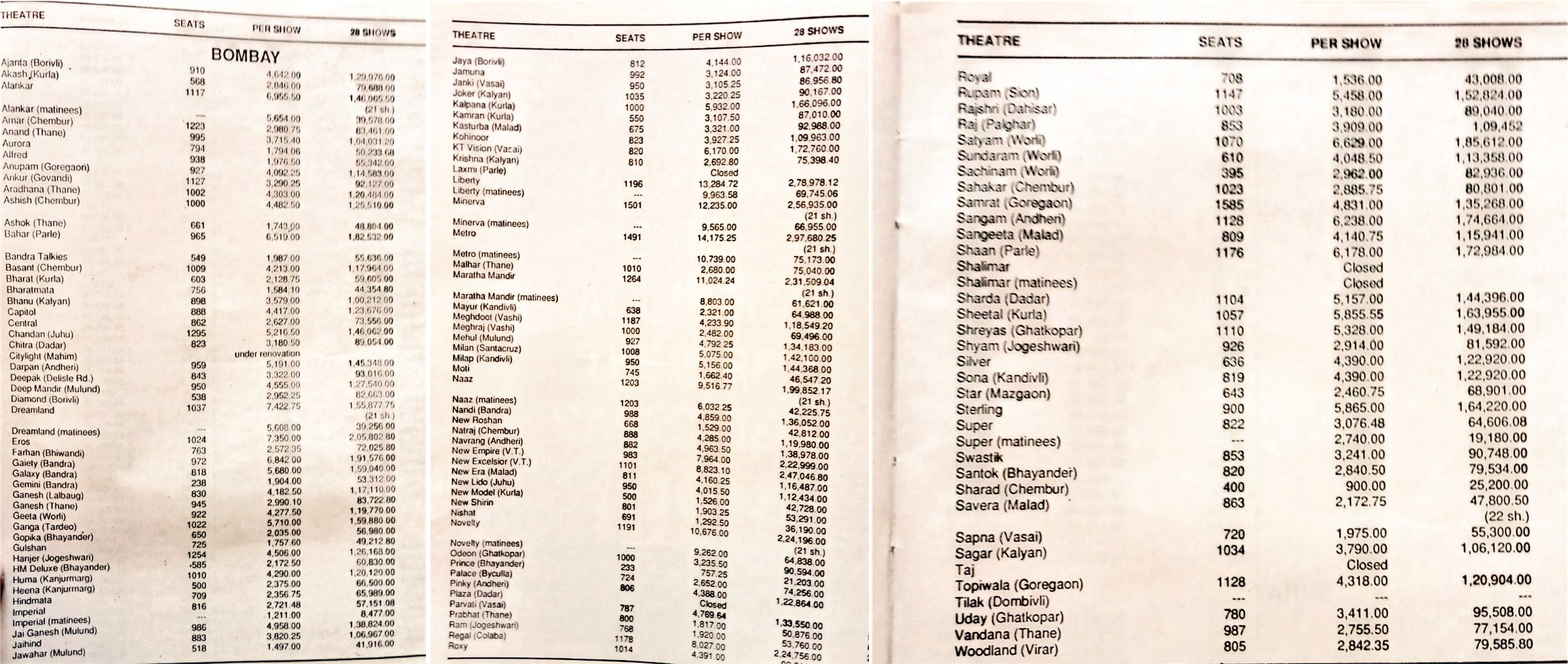

- When you add this to the 50% entertainment tax that some states imposed on tickets prices, and the formidable challenge of film piracy in India, the result was that by 2014, despite having 4x the population of the United States, India had actually lost cinema screens since the 1980s - dropping from over 20,000 to just 12,000 - while China expanded from under 7,000 to 50,000+ screens in the same period.

This state of affairs was actually summed up beautifully by Aamir Khan at WAVES 2025, where he said - “Now, even in this 10,000 [screens], half of them are in the South and the other half is in the rest of the country. So, for a Hindi film, typically, it is around 5,000 screens. Only two per cent of the population in our country, which is recognised as a film-loving country, watches our biggest hits in theatres. Where is the rest - 98 per cent - watching a movie?”

Back in 2015, ten years before WAVES, all of these research threads eventually led me to the root of the problem - that India has a chronic lack of screen density.

Say whaaaaaaaaa? [I didn’t actually say that. I said ‘Can you please elaborate?’, but that looked a little boring here]

India - which you would associate as being a film-mad country where everyone watches movies and cinema surrounds us all the time - is severely under-screened. When you compare the number of screens per person in India vs the United States, and particularly in China, you start to see the problem.

What’s the reason behind this paucity of screens?

So first, again we’ll do a bit of history on the film exhibition sector.

I imagine for a lot of your readers, when they think ‘movie theatres’, they think of a multiplex, and let's be honest, a PVR INOX multiplex. But both PVR INOX and the multiplex concept are relatively recent - about 30 years old. The story of PVR actually begins with Village Roadshow, an Australian company, partnering with Ajay Bijli in the mid-1990s to bring international cinema standards to India.

Before this, the Bijli family was mainly into the trucking business, but owned a single Delhi theatre called Priya Cinema. Mr. Ajay Bijli first took ownership over the operations of that theatre and improved the standard of the experience there. He focused on a more upmarket crowd, among other things offering the latest Hollywood movies.

Before PVR, Indian cinema exhibition was a completely different world. The few premium theatres that existed - like Chanakya in Delhi or Raj Mandir in Jaipur - were standalone palaces that charged different prices for different sections: balcony, box, first class, second class. These prices were often mandated (and capped) by the government.

PVR revolutionised this by creating the concept of uniform pricing and standardised comfort. Suddenly, everyone paid the same price and got the same experience - air conditioning, proper sound, clean facilities. They also came in with smaller individual theatres with reduced seating capacity, but many more theatres located in the same property. It was genuine democratisation of the cinema-going experience, at least initially.

But the real culture of film-watching in India was forged in single-screen theatres. These were often massive 800-900-1000 seat halls, often without air conditioning, where watching a movie was a communal, almost religious experience. People would whistle, clap, throw coins at the screen when their favourite star appeared. Film stars themselves became deities. Films like Sholay and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge would run for years in the same theatre, becoming cultural events rather than just entertainment. The single screen was where cinema became part of India's social fabric - families would make it a weekly ritual, young couples would find their only private space together, and entire communities would gather for big releases.

Even beyond the traditional single screens, India had a rich ecosystem of alternative exhibition formats that I discovered during my research.

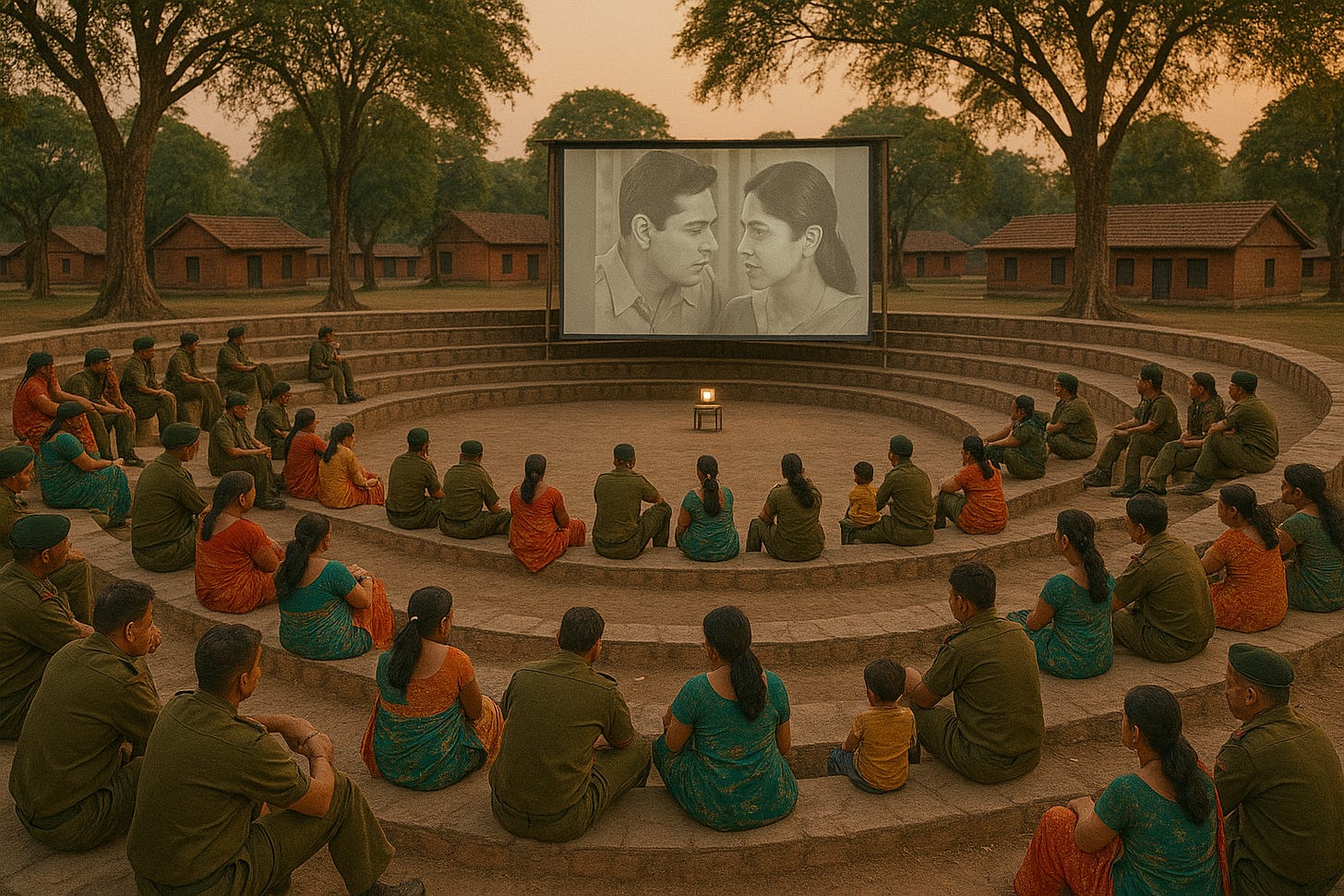

In Tamil Nadu, there were 'Palli cinemas' or ‘tent cinemas’ - temporary structures that would pop up during festivals. There were also ‘Tambu talkies’ or 'touring talkies' where people (and NGOs) would travel with trucks, set up portable screens, and show films in villages. During melas and exhibitions - called ‘Numaish’ in places like Gwalior - temporary cinema structures would be erected. I grew up in Jabalpur and my father served with Signals, so we followed his posting routine all over the country. The Indian army had open-air amphitheaters - where we used to watch films, which gave me some of my most memorable cinema experiences growing up. All of these types of screens served communities that formal cinema infrastructure couldn't reach.

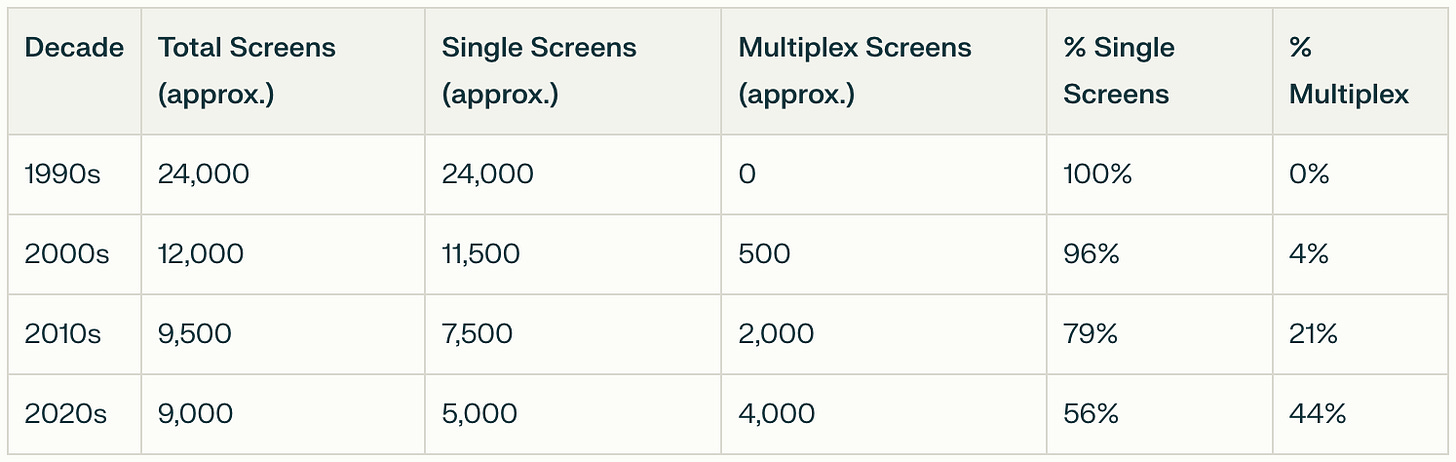

What's happened over the last thirty years is that multiplexes have systematically captured the urban, premium market while single screens have withered away, either being shut down completely or sitting in decrepit conditions because their owners don’t have the funds to renovate and there’s no economic case to modernise. Initially, PVR started at ₹100 per ticket when single screens charged ₹30 - a 3x premium that held steady over time. But what began as democratisation gradually became premiumisation. Today, a family of four can easily spend ₹5,000 for a movie experience versus ₹1,000 at a single screen, when you include things like parking and food and beverage prices.

The result is predictable: people who used to watch four films a month now watch one film every few months. What used to be the cheapest form of entertainment is now prohibitively expensive for many (it’s why South Indian film industry continues to flourish and take mindshare and market share from Bollywood because its still affordable for most).

Ultimately, in most parts of India, we've created a more comfortable but far less accessible cinema culture. Single screens are shutting down at an alarming rate, and this has been accelerating over the last three decades. In some cases they get replaced by multiplexes, but definitely not at the rate required to maintain or increase screen penetration. Because multiplexes need significant investment and regulatory approvals, they can only operate in established urban markets, leaving vast swathes of India underserved.

After PVR and INOX merged during the pandemic, it means India is largely moving towards a single-player system when it comes to film exhibition, which is a troubling situation for the entire industry.

Got it. Maybe we can now bring this home towards your solution. What was it that finally convinced you to step into the fray here?

So, if I told you that the number of single screens are shutting down today, and that people are deciding not to open new theatres, what would you assume was the cause? You would probably say it’s because of the rise of OTT platforms, right? But that’s a simplistic answer. I’ll give you my last bit of historical info and then we can get to my solution.

In actuality, the lack of screen density comes down to two factors, both of which are related to each other - 1. Regulation, and 2. Real estate.

On the first point, what’s interesting is that cinema was actually part of India's original urban planning mandate. When cities were being developed post-Independence, municipal authorities allocated specific land for entertainment - just like they did for schools or parks. Mumbai had its Chandan Cinema, Delhi had Chanakya. Licenses were issued to support the number of cinemas per population cluster in different metro districts. They were seen as integral to how communities were supposed to function.

In 1955, Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru addressed a seminar of leading film artistes in Delhi under the auspices of the Sangeet Natak Akadami and described films as a “tremendous thing”, with an influence in India, “greater than the influence of newspapers and books all combined”, though he did add jocularly that he was not sure of “the quality of the influence.”

- Seema Chishti (The Journey Since 1947-I: Cinema Halls)

But over time, this created a regulatory nightmare. Today, if you want to set up a cinema theatre, particularly in metros, you need 70+ different permissions and licenses before you get started. Fire department, municipal corporation, electricity board, traffic police, entertainment department - water, plumbing, sewage management - each one requires separate documentation, fees, site visits. The whole process takes 2-3 years even if you have money and connections.

As I tell people, if you look at any project where you have to spend 3 years just to get permission, then 2 years building, your project timeline is 5 years. People build car factories in less time. To build one cinema screen shouldn't take that long. By the time you actually start operations, your capital costs are already astronomical because you've been paying interest on loans for half a decade.

And real estate?

This was the final blow. So India's 1991 liberalisation - while it freed up many aspects of the film sector (like removing the mandated cap on ticket prices, which was one of the tailwinds for the success of PVR) - it triggered massive real estate appreciation in urban areas. Suddenly, the prime land where historic cinema halls sat became worth 10-20 times what it was in the 1980s.

So cinema operators faced this impossible squeeze: operational costs skyrocketing due to higher rents and property taxes, but ticket prices were either still capped by state governments or just could not be raised to the point where they could cover costs sustainably. The math just stopped working.

If you've been to Delhi markets like Khan Market or GK1, you'll notice they're not really local markets anymore - they're all restaurants and big brands now. That's because real estate prices don't support traditional retail businesses. The same thing happened to cinemas, except they had additional constraints. They couldn't pivot their business model, and they were stuck with price controls.

This hit single screens the hardest. Unlike PVR, which could leverage scale and access capital markets, and which continued to push their prices up because of their dominant position and their target market, independent family operators found themselves squeezed from every direction. Many just sold to developers and got out of the business entirely.

So if you, Rahul, are an entrepreneur who wants to get involved in film exhibition: given the costs of setting up a new theatre, the rents you’ll have to pay in Mumbai, the 70+ permissions and regulations you need to get, the 3+ years it’ll take you to get started, you would probably want to do something else with your time and money. That was my starting point.

So where did you arrive at at the end of your research?

By 2015, I was convinced there was a need for a certain type of product. My conclusion was:

that if you could build a movie theatre with less than ₹1 crore of set up cost, with a capacity of 120-150 seats, where the operational costs were less than ₹2 lakh per month, as a film exhibitor this wouldn’t just give you a positive ROI but a very lucrative ROI.

if you could find a way around the maze of onerous regulations and the high real estate prices - the two biggest incumbents to single-screen operators - you could get your business off the ground cheaply and quickly.

if you managed to do both those things, you could charge a lower price per ticket, meaning that more people could enjoy watching movies, and one individual or family would be able to come back to watch several movies in a week/month (vs once every few months)

that would translate to your theatre having a significantly higher occupancy than what you’d get at an average multiplex these days (~20% for PVR INOX in FY25), and the Indian film industry would become more inclusive, successful, and sustainable overall.

And that was the business case for PictureTime.

II] Plot Building

Thank you for setting the table for us. How did you start developing the actual solution?

Given the business case, I started my conceptualisation with two main principles in mind - mobility and portability.

First, mobility was important to circumvent the regulatory burden of setting up a ‘permanent cinema’. In the case of a ‘touring’ or ‘temporary’ cinema like the ones I highlighted earlier, most states didn’t even have a legal framework to regulate this, and for those that did, you needed only 3-4 permissions vs the 70+ permission that would have been required to set up a permanent exhibition hall. A mobile solution was the quickest way to get started. Separately (and simultaneously), we also started a decade-long process of lobbying various state and central government officials on the need for a new regulatory framework for a simple theatre set up i.e. a “no frill cinema” that was a lightweight alternative to the full-blown sophisticated multiplex set up (I’ll double-click on this in a bit). We knew this would be a longer fight so the easiest way to get started was to work with a temporary theatre set up.

Anyway, on the ‘portability’ side, I had this vision for a truck that could get transformed into a cinema hall - almost like this inflatable balloon-like structure that could emerge from the truck itself. Ideally it had to be some kind of solution that could be set up and taken down in a few hours by a team of five people - so you could optimise for speed too. That’s what we started with. The first prototype was much simpler than what we have now, it was basically just vehicle-mounted projector set up.

We were mostly developing this product in our office garage in Delhi. We piloted it at the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in Goa in 2015. There was a near unanimous appreciation. Lots of people told us they had never experienced a movie like that, with that kind of sound quality, so it helped to validate some of my ideas.

I knew that I didn’t just want an open-air set up though. To get it to a modern cinematic experience, we needed an enclosed structure, something like a tent. That was the big piece of the puzzle.

That came with its own engineering challenge?

Yes, because in a tent, the question is how do you get the right acoustics? Installing a fully decked out multiplex-level acoustic set up would have added considerable time, cost, and complexity to the operation. That was out of the question.

So I took some time to study sound engineering. We had some great people on the team that helped with this too. We realised that if you could design the interior walls of an inflatable structure using a certain pattern, this would effectively mimic the acoustic arrangement used in a modern theatre in terms of how the sound reverberates off the panels. It worked beautifully. As of today we have three patents for this structure (relating to the design, the set up process, and the system).

Once the sound acoustics were addressed, the other thing I was concerned about was sound proofing. But that turned out to be not a big concern, because we were targeting the interiors of India where there wasn’t much public around to disturb.

Moreso, when we did our research, we found out that not only was it not a disturbance, but in many parts of rural India, people don’t mind where sound goes. Everyone overlaps in everyone’s space and people are happier for it. It’s common to hear the sound of a loudspeaker in daily life. In fact, we heard stories of people putting a loudspeaker on their house, and running the entirety of Sholay in audio form, so everyone could gather and listen! That's part of the culture of film appreciation in India’s interiors.

After acoustics and sound proofing had been addressed, all our focus was on creating the best possible sound experience. It’s no point getting the best films if we can’t exhibit them the right way. That’s why we offer a Dolby 5.1 listening experience [which basically refers to a surround-sound set up with five speakers positioned around the audience and one subwoofer for deep bass, creating an immersive audio experience that matches what you'd get in a premium multiplex]. All together it took us roughly 18 months to get that first prototype together.

I’m curious, where did the inspiration for the actual structure come from?

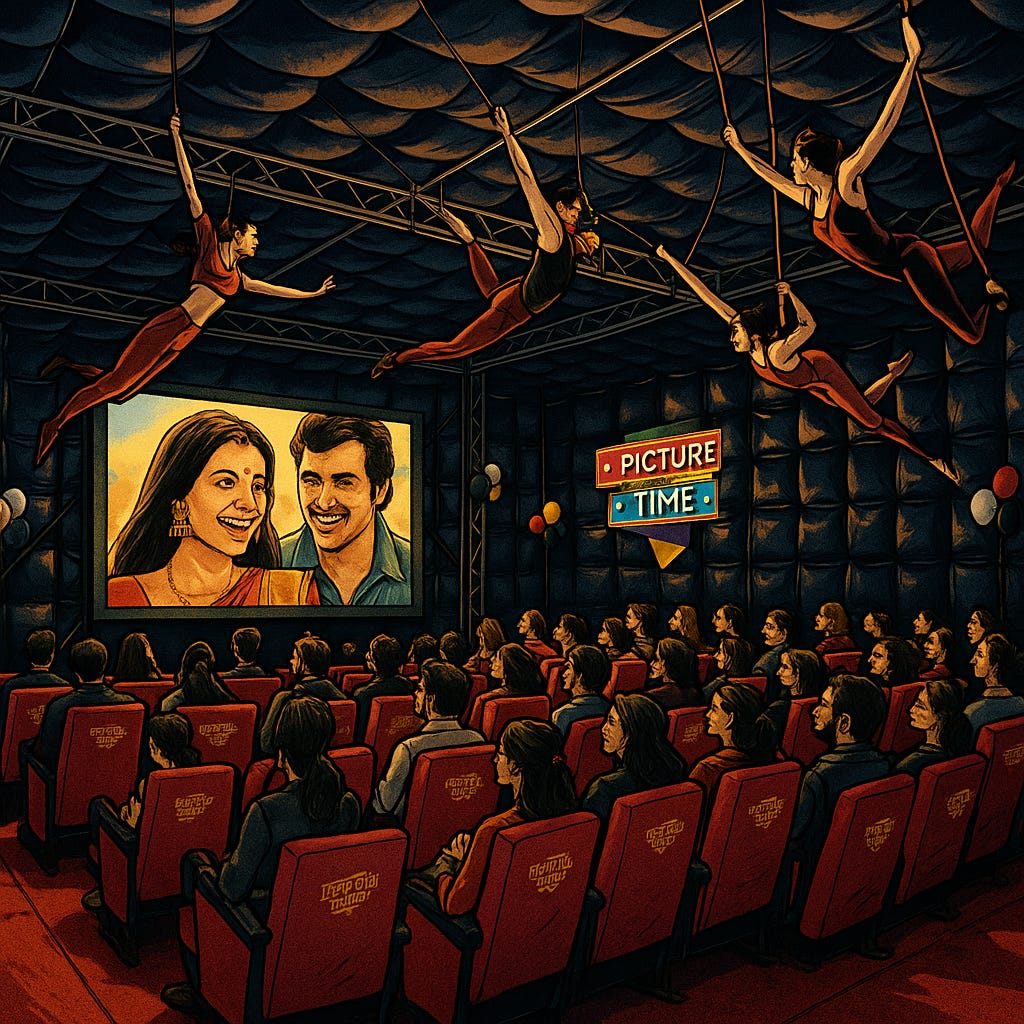

A few places. One, I had grown up around army cantonments where we always had temporary screening set ups in open amphitheatres. I had also researched these ‘Numaish’ portable exhibition set ups that were common during fairs and festivals in North India. And also the circus.

The circus was always interesting because it’s like, the show comes into your town, you visit and enjoy, and then it moves on. It’s a temporary structure that goes from place to place every month. Many circus tents were made of modern materials, they were air conditioned, had comfortable seats, and gave people a good show. So that was a model for mobility and portability.

From each of these examples my main takeaway was that people are more concerned with the quality of the experience than they are about the physical infrastructure. So my focus was in ensuring the best possible temporary cinema experience. That meant air conditioning. It meant global standard sound and video quality. It meant top quality projectors and seats. Essentially we wanted it to be where if you stepped in to one of our theatres, you wouldn’t know it was an inflatable structure that was only erected in the last few hours. You would think it was like any other normal theatre.

And for people that have never stepped into a PictureTime theatre, what’s the actual material you’ve used?

In 2015, when it came to designing an inflatable cinema hall, I realised there were lots of ‘magic’ materials in the world. To create our cinemas halls, we currently use a PVC-like material. In India nobody manufactures this at the right quality at the moment so we have to import the material and then we build the structure here. Today we are looking at upgrading this material so we can create eco-friendly acoustics panels. We’ve also figured out how to make use of recycled plastic panels to create walls, so our new ‘fixed theatre’ set ups will use the upgraded materials vs the current inflatable cinema theatres. I was the original concept designer in the team and of course we then hired the right people. Collectively we had to become experts in material science, understanding how to make this structure safe and stable.

In 2016 and 2017, once we figured out the right material and then the right quality, and we knew it would be an inflatable structure, then it went on to how do we stitch it together, how do we make sure that if someone punctures this ‘balloon’, it doesn’t collapse. We had to test whether it would fall down. We had to figure out how to make it sturdy, how to make it storm-ready, rain-ready - all of these were design questions. That’s again where the patent comes in. And today our structure in Ladakh faces extreme weather, there are extreme storms at our Telangana location, Vizag extreme rain, Rajasthan extreme heat, Tamil Nadu tropical. So our theatre is now an all-weather theatre. We have a world-first patent for this Acoustic Enabled Inflated Enclosure (AEIE).

And the last piece of the puzzle was to figure out how to get all of this into a truck. When we were thinking through the design, we had to optimise to fit everything into a relatively small vehicle. India has a lot of MDRs - major district roads - vs wide-laned highways, which meant we didn’t have the luxury of filling up 40-feet containers. We had to work within the confines of a 24-foot container. The space in the container was optimised in a way that incorporated 120 chairs, a projection room, air conditioning, the inflatable structure, and safety material. All of this was snugly packed into a 24 by 6 by 8 container. It was a unique design. We ran a bunch of experiments in our garage in Delhi to get it right.

Once we sealed the design of the theatre, we contracted an Ambala-based company called JCBL to build it for us. It was faster than doing it ourselves and it means today we can produce 25 such theatres in 30 days, making us the fastest cinema builders in the world!

Got it. So once you finalised the design, what next?

So once we had our working prototype, we started demo-ing it to people from the entertainment industry. We demo’d it to filmmakers like Neeraj Pandey, Sheetal Bhatia, Kabir Khan - they all loved it. We met the Baahubali team, who also loved it. We had a lot of encouragement from the film industry groups, all across India - North and South. Everyone thought it was a clever solution.

We demo’d it with people too. We did a big unveiling at the International Film Festival in Goa in 2016. When we saw the response there we knew we were ready to take the next step, to get this into the market.

So after you had the first prototype and you proved the concept, how did you commercialise the solution? How did you get started?

Our first instinct was to look at the states which had the poorest screen density - places like Chhattisgarh and Odisha. Maybe someone else would have dismissed these as ‘poor’ states, but we didn’t see it that way. For instance, both Odisha and Chhattisgarh have a rich history of arts and culture. For example, there has always been a strong tradition of Jatras in Odisha, where people pay upto Rs. 500 for a ticket to watch a night’s worth of performances.

So it validated my thesis that if we could offer the latest movies in a nice cinema setting, people would happily pay ₹70 to ₹100 for a ticket. So I began reaching out to different state governments.

I should add that there was a positive response even outside of these states. For example, I had a conversation with the then-Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu. She was doing this amazing programme of food subsidisation under the Amma Canteen banner. At the time she had an idea to set up Amma Theatres too, to offer citizens a form of subsidised entertainment. The plan involved setting up 1200 theatres in 1200 clusters of Tamil Nadu at a cost of ₹3 crore each. I showed her how we could eventually cover the same population with 300 movable screens at less than Rs. 1 crore cost per screen. She immediately saw the potential. I remember her talking about how this would help the citizens, the people, the government, and the local film industry. Her rationale was that if someone has ₹30 in their pocket, and they have a choice to buy a peg of alcohol or get an amazing cinema experience, hopefully they would pick the latter, and that would be the best outcome for everyone.

So there were lots of these kinds of initial discussions and I took it as a mission to get these Chief Ministers on our side.

And where did you actually launch?

Our breakthrough came in January 2017 with the Chief Minister of Chhattisgarh, Mr. Raman Singh. I had written to him about our solution, about how it could have an enormous socioeconomic utility in his state. The last line of my email was that it would ‘make people happier’. I think that’s what got us the meeting.

We met in Delhi and told him what we were trying to do. We said our theatres would allow people in his state to watch the latest movies on the first day, first show - in air conditioning too. We said they could use our theatres to do video conferencing, and even to provide people with wifi. And then - I don’t know if this was right or wrong - I wanted to convey the importance of cinema to Indian society, so I remember saying that, respectfully, you could make the case that Amitabh Bachchan and Shah Rukh Khan have been more responsible for improving the quality of people’s lives than any politician! He said ‘Okay. Let’s see if what you’re saying is true. We can give this a shot as a trial. Tell me what you need from me.’

To his credit he actually gave us space in the foreground of his official residence in Raipur to run a pilot. At the time the film Rangoon was just about to release. I was able to reach out to the director Vishal Bhardwaj through my friend Ashok Sharan, and asked if he would premiere it at the Chief Minister’s house in our inflatable cinema hall. He said yes.

Not only that, he even agreed to have an interview with the CM via video conference within the theatre during the screening. Through another connection we managed to reach out to the cast and crew of Naam Shobana, which was also released that year, and we managed to get actress Taapsee Pannu to also join in for a chat on video conference during the interval. It couldn’t have gone better.

So we got Rangoon premiered successfully before its official debut, and we proved that we could set up the entire operation in four hours. Mr. Singh said ‘okay, you’ve done your part, now let me do mine’. He immediately connected us with his secretary, who helped us source two viable spaces for our first inflatable theatres in Rajnandgaon and Pandaria. That’s how our commercial operations started.

It would be helpful to understand here what these types of arrangements look like - does the state pay for the set up? Who manages the operations?

No, we pay for the entire set up. So for these first two theatres, the set up cost was around ₹50 lakh each. The government helped us with things like getting the relevant licenses, they gave us subsidised land rental and electricity costs. They supported us in other ways too. But after that it’s all us - the promotion, programming, ticket prices, popcorn prices, advertising etc.

Our belief has always been to manage the entire operations ourselves, including the set up. The reason is because we never wanted someone else to take advantage of the quick set up cost but then start exploiting the customers with higher ticket prices or compromise some other part of the experience. So all the theatres we’ve launched so far have been self-funded and managed.

That being said, for the next phase of the company we’re looking to get into franchise arrangements with independent operators. So that means we’ll get partners to contribute the financial investment and the human resources, and we’ll provide the training and the Standard Operating Procedures. We’ll still manage the programming, we’ll still dictate the prices etc, but it’ll be more hands off when it comes to everything else. The main thing is for the experience to still be top quality, and to still be affordable and accessible.

What was the actual return on these first two theatres, if you don’t mind sharing?

We basically did around ₹1.8 crore in revenue in the first year from those two theatres. That includes ticket sales, food and beverage sales, and advertising, which was a big part of the turnover. For example, lots of companies that wanted to reach this audience advertised their products in our theatres.

The state government also made major use of it for outreach programmes. They realised it’s a much more effective way of educating and reaching citizens than hoardings or posters. Outside of just advertisements, we could basically facilitate real time video conferencing between government officials with citizens. So state officials would have conversations with attendees during the interval - they could ask them their opinions on a new sanitation scheme, a new clean water scheme, the Ayushman Bharat scheme etc. It was a completely new channel, and those kinds of things made a big difference to our revenue numbers.

The actual profit we made on those two theatres in the first year wasn’t a lot, but it was good validation of the business model.

So once you had your proof of concept, now you have your first taste of commercial action. Was the next step to turn on the afterburners? And was all of this work bootstrapped at this point?

Outside of personal funds we had raised a little bit of external funding from individual angels and friends and family that supported our early work. Towards the end of 2017, on the back of our proof of concept and pilots, we had received a term sheet of ₹10 crore from a local VC fund, which I was hoping to use to open 10 more screens, and then go in for another round. But things played out a little differently.

In December 2017, I serendipitously ran into Mr. Ajay Relan [doyen of private equity in India], who served on a number of corporate boards in the country, notably that of HT Media. I bumped into him along with a common friend, and when he heard I was in the film exhibition business, he said ‘let’s have a coffee’. It was supposed to be just a casual chat, but after listening to my story he asked if we were raising funds. I said ‘yes, we have a termsheet of ₹10 crore.’ He said okay, and took my number, and I went along with my day.

A few hours later he called me and asked how big our boardroom was, and if it could accommodate 20-24 people. I said it can accommodate 16 comfortably but we could add some chairs. That afternoon he showed up to our office with the entire HT Media board, among other people. I gave a presentation to the assembled party. After I finished, he stood up and said to the entire group ‘this is the story to back - this is a product that rural India needs, and this is the future of rural marketing…but Sushil is making a mistake. He doesn’t need 10 crores, he needs 100 crores.’

Was there a real offer?

Very much so. But I said immediately that I didn’t have a plan for 100 crore. I had a plan for 10 crore. We were only 14 of us in the company at that point. My priority was to improve the product and slowly build out the team. I was thinking product, not scale.

But the discussion in the room was about how to push the pace on everything. Everyone was excited about adding rocket boosters to our operations - think fast, move fast, scale fast etc. I ultimately put my foot down and said that the maximum I thought the business could digest was ₹25 crore. Mr. Relan said that amount was too small for HT Media, but he decided to syndicate the entire amount himself. I was leaving for New York for a personal trip in the days right after this meeting, so he told me to cancel the other termsheet I had, and he wired me ₹2 crore before I left for my trip, before doing any due diligence, and before we even had anything signed! He said ‘you’ll have the rest of the amount by the end of your trip’. And he kept his word.

The problem was that the money kept coming! ₹28-30 crore had made its way to our bank account, but I called and said we need to cool it because I didn’t want to dilute our equity any further. The extra amount was returned. We officially announced the ₹25 crore fundraise - we called it a pre-Series A round - in early 2018. It was led primarily by Mr. Relan but also included other HNIs and individual investors, notably also the Hero Family Office. A new board was constituted. We had 10 of our mobile cinema units operational by this point, covering territory on ground in Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. The goal after the fundraise was to expand this roster to 100 mobile units within 12 months.

As it tends to happen, things started out well. But if I was to give any aspiring entrepreneurs advice here, based on my own learnings over the next year, it would be to be very careful about getting greedy about funding, and to make sure you know who you’re partnering with.

As the weeks went on it became clear that we had taken on board too many people with too many differing views on how to build the business, and a few that had no clue about our original mission. It became clear that some had gotten involved to flip the business for a quick profit. There were loud voices calling for the company to do everything all at once. What they failed to understand was that this wasn’t a traditional tech product, this wasn’t some piece of cloud software. It’s the same reason why we haven’t see many VC-backed hard engineering products from India - these ventures need patient capital. If you have patience now you will get your big returns later. And our company had been built on real engineering. Our ‘products’ needed to be carefully nurtured if they were to grow properly.

So six months in I said I didn’t think I was the right person to lead the company in the direction that had been chosen. I had originally suggested hiring a COO or Head of Operations, but ultimately they went and got in another CEO from outside. I took a backseat with respect to executive decision making. I mainly focused on product development. Also I took up running and golf, which was a nice change of pace. I could see the mistakes the company was making, but I stopped sharing my input, which eventually led the company to the brink of disaster.

A year and a half later I approached the board and said I would like to come back as CEO. I couldn’t see my company be destroyed from the outside in. I wanted to take over the driving seat again for the good of the organisation. It helped that there were people from inside and outside the company who were in my corner. For example, [director] Satish Kaushik had become a fan of PictureTime after seeing our pilot in Goa, and he had been voluntarily promoting it all over the country. I invited him to join the company as an advisor, and he was one of the biggest supporters of my plan and vision.

So I made a very tough decision in September 2019 to purchase back shares from several investors, who in my opinion had been a counter-productive influence. I spent most of my savings - ₹12.5 crore of my own money - that I had made with my first venture. I could finally install a board that was aligned on the path ahead. For the six months after, it looked like we were firmly back on track and set for a good phase of growth. Of course, I couldn’t have known that six months later we would be in a pandemic.

III] Reset

I remember it was around this time that PictureTime actually showed up on my newsfeed. From what I had read back then it sounds like COVID had forced your hand in a number of ways. Could you talk about that period, immediately going into the pandemic and how you eventually came out?

My guess is that all the investors who sold their stake to me were very relieved with their decision! Everyone assumed this was the end for us. All our momentum - after finally getting the product where we wanted - was halted. After the pandemic started it was the hospitality industry and the film industry that were immediately placed on life support. We had even received a funding offer of ₹50 crore at the start of the year that was pulled off the table when everything shut down. We had around 37 operational screens going into COVID, and they had to be closed with lockdown too. My team was naturally worried, but I told them that we’ll figure something out.

A few weeks into lockdown, we got a call from the Tata’s asking if we could help them set up inflatable structures that could be used as ICU units. It’s not something we had ever considered but my team was up for the challenge. So in less than 30 days we delivered a temporary support facility for the Tata Cancer Institute at the St. Xavier’s hockey ground in Parel in Mumbai. This facility was used to provide emergency medical care as well as COVID testing, and could accommodate 75 beds in all.

This got the attention of the media. So by the second wave of the pandemic, we had set up more than 30 inflatable hospitals for partners like Apollo Hospitals, IIMS, AIMS Rajkot and others.

Our facilities were being used all over the country, even as far as Shillong, Assam, and Kashmir. These facilities could be bio-contained. They were oxygen-ready ICUs and helped plug urgent infrastructure gaps that the country was dealing with at the time. Many of the state governments that we had relationships with because of PictureTime now called on us to help on the medical side of things.

Many of our actual existing mobile theatres were also converted to ICU units and testing units. All in all I believe we had facilitated 37 hospitals and 1400 isolation wards and ICU wards around India.

That’s amazing. I assume these were commercial arrangements too? Is that what helped you guys navigate that period?

Yes. So we made around ₹22 crore in revenue for the work we did during the pandemic on the medical front. It was not an insignificant amount and it helped us stay alive for those couple of years. In a strange way we were able to prove to ourselves that we were capable of executing quickly, and at scale.

The work was of course very gratifying and we were proud to do our part to help the country. The problem was that people had begun to think of us as a healthcare company. Between the public and private sector, we had received orders worth ₹400 crore for a variety of healthcare facilities coming out of the pandemic. It left us in a conundrum, whether to continue down this path, to take the necessary steps (expand team, hire specialists, do a big funding round etc) to pivot completely, or to get back to our original mission.

There were many conflicting viewpoints here, which was understandable. Lots of people said we would be stupid to turn down these orders - which was tangible, lucrative revenue. As a single founder I was in a conundrum. Ultimately my heart told me that we should get back to our core business. My rationale was that there were lots of companies catering to the healthcare sector, but there was no one looking to preserve the future of cinema in India. I told my shareholders that I had started this company as a film company, and that’s what I wanted to continue.

So how did you get back on track?

One positive thing from that period was that we were able to plough back all our earnings from the healthcare detour back into setting up new theatres. Coming out of the second wave, we expanded our business model a little bit. We would still have our mobile theatre trucks moving from place to place. But we started a new line of business of setting up permanent theatres in remote parts of the country too. The first of these, in August 2021, was set up in Ladakh. I believe it still holds the record as the highest theatre in the world.

We launched it as part of the Himalayan Film Festival which was being inaugurated that year. We had the Ladakh Buddhist Association president Thupstan Chewang and [actor] Pankaj Tripathi present for the launch event. This film called ‘Sekool’, on the Changpa Nomads of Ladakh, was screened at the launch event, but over the course of the festival we were able to feature mainstream films like 83 and Shershaah too.

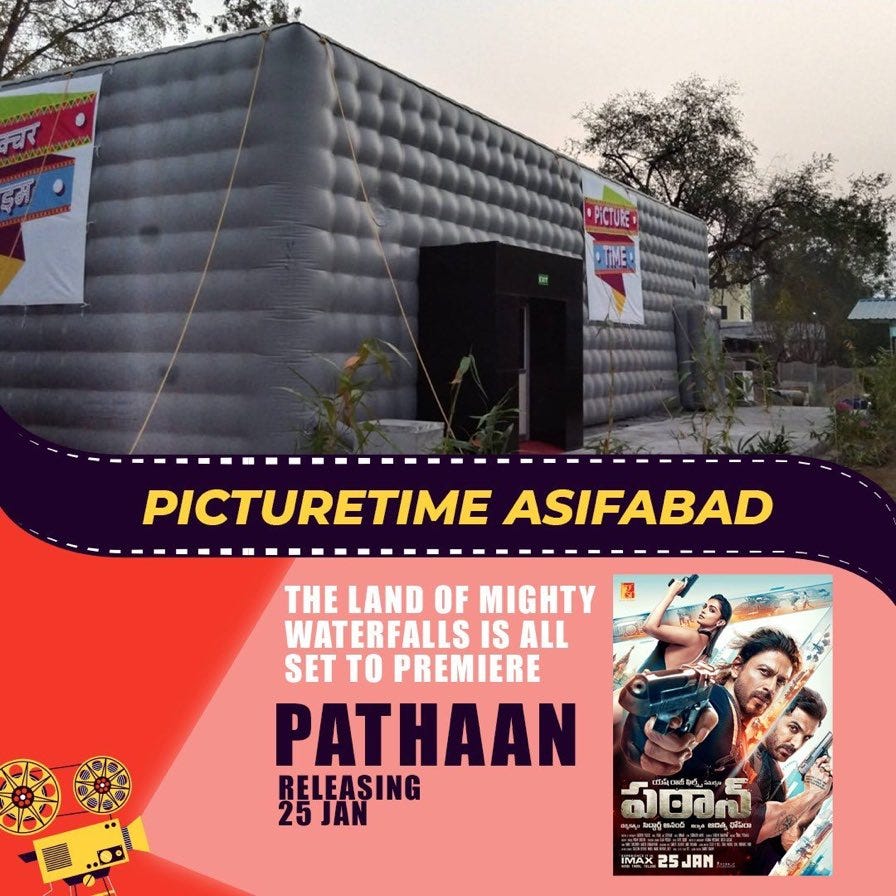

Then we followed that up with the first theatre in Asifabad (Telangana). Here local Self Help Groups (SHGs) contributed ₹30 lakh of the total ₹50 lakh investment so they could finally have a cinema hall in their community, which could generate employment and a sustainable income for the local women-run SHGs.

So slowly and gradually we kept installing these fixed theatres, in Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra etc. In 2021-2022 it was still a tough situation, because some theatres still had 50% seating restrictions. Others had resumed 100% seating but there was still very little footfall.

But when RRR released in 2022, it gave the entire industry hope. Mr. Rajamouli’s film was the kind of spectacle that finally got people back into theatres, and many of our halls - the mobile ones and fixed ones - had 100% occupancy for many weeks. We even opened six new screens just to coincide with the launch of the film. It was one movie that provided some signs of life for the entire film landscape that ‘yes, people will eventually come back’.

2022 was not a great year for the film business but it was one that carried hope. 2023 was a better year. We had a string of crowd-pullers like Pathaan, Jawan, and Gadar 2 that all released in 2023 and made it seem like things were coming back to normal. It felt like we could finally put COVID behind us and start to look ahead. We were back to building screens instead of shutting them down. That year we got another major funding offer of ₹50 crore from one of India’s industrial giants - a mix of equity and debt - that we ultimately turned down. Instead we did another small friends and family infusion to support the new work.

Right, so I’d love if you could bring us up to speed on where the company is at today - maybe we’ll start with the scale?

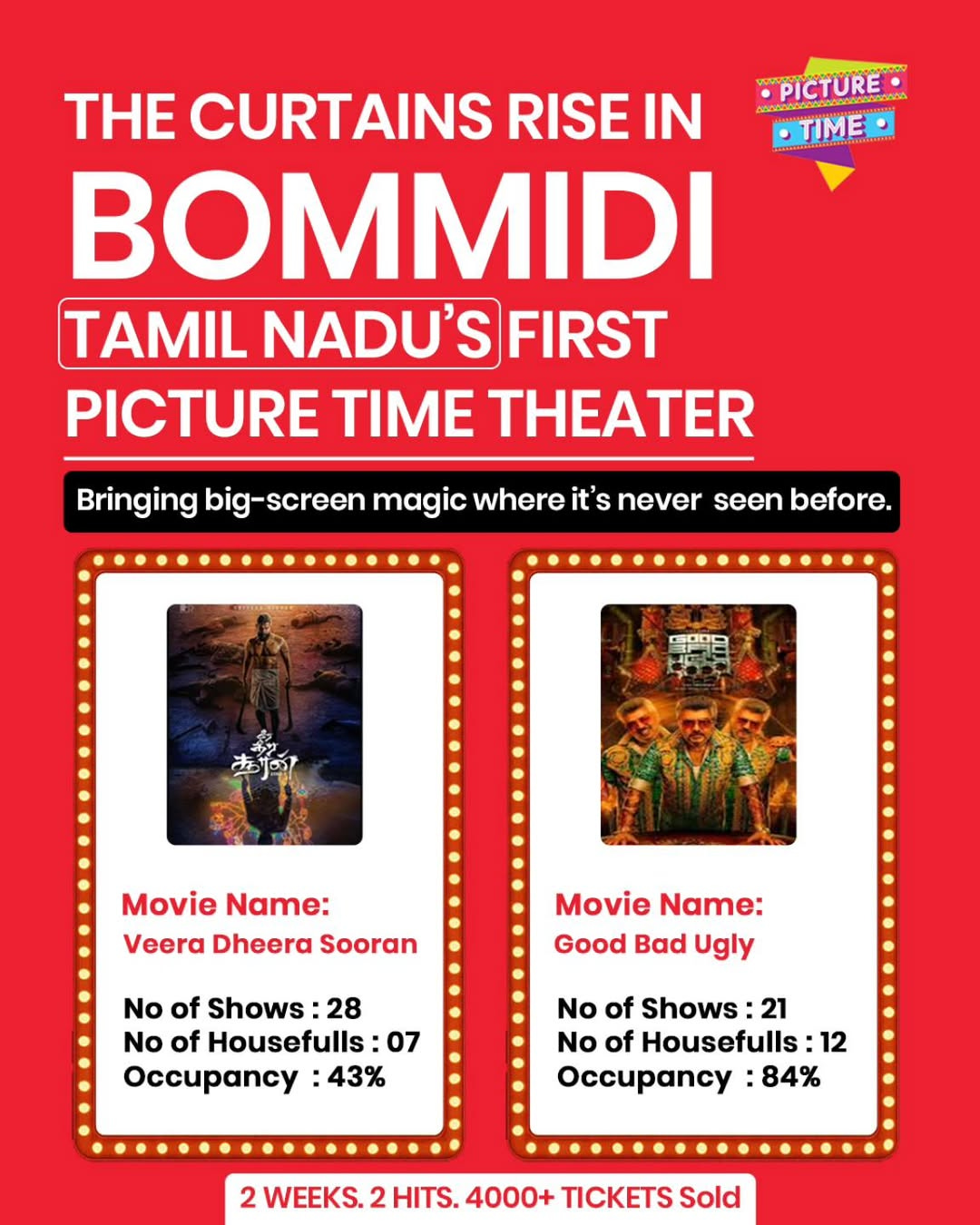

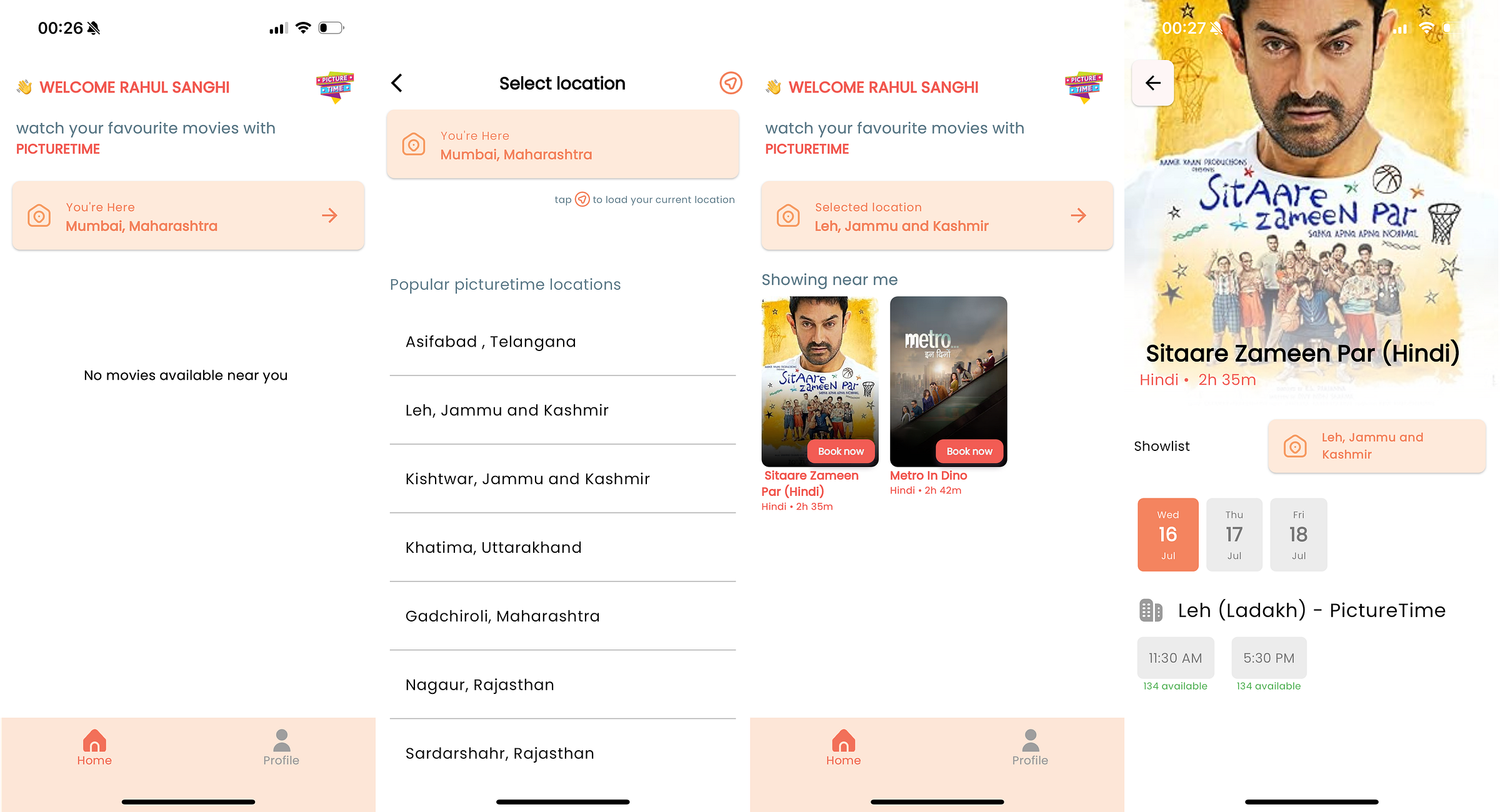

So today we have 21 operational screens - a mix of fixed and roving screens. It’s taken us a long time to get back into rhythm after the pandemic, but it finally feels like we’ve turned a corner. For example, I don’t do much outbound pitching anymore. Now we have state governments, defence bases, local districts, and potential franchise operators reaching out to us, and that’s ramped up in a big way after WAVES. We are much more careful about picking the right partners.

We’ve spent the past two years rebuilding our capability, our team, improving hardware and software on the tech side of things. We’ve ironed out a standard operating procedure. There have been some major wins on the regulatory side that puts us in a great position. We’re now in the market for a $25 million fundraise, ideally with impact-focused investors who understand media and entertainment, and see the world in the same way we do. We are a growth-ready, scale-ready company now, and the unit economics of our theatres would be attractive to external investors.

At this point we’ve actually identified 428 locations in the country that would be good short-term markets for PictureTime offerings. Here’s how we think about this. There are roughly 736 towns and cities in India with over 1.5 lakh people. Right now only 258 out of those 736 have cinema screens. Those are mainly Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities. Tier 3 there’s a general lack of screens. So out of that 736 total figure, we think 428 locations would be ready for us tomorrow. Long term we’ve earmarked around 1500 locations, but we’ll need to approach this step by step. Our current objective is to set up 3000 screens over the next 5-7 years (25-40 per month), which would be a significant scale up from here, dependent on funding, hiring, capacity building etc.

Maybe we can unpack all of those one by one. For starters, could you elaborate on the logistics of each of the two models you currently operate?

Sure. As you know when we started we were mainly focused on the travelling theatres. While I was convinced that there was a latent desire for cinema in remote parts of the country, the idea still needed validation. My thinking was that we could first take our product to different locations and assess local demand.

So we would pick our location and then announce ahead of time (using various social channels, local newspapers, local influencers etc) that a PictureTime theatre would be arriving for a week, for two weeks, for a month etc. We would run the cinema in that town for that period, and then pack up and move on to the next place. The entire set up and dismantling can happen in ~2.5 hours. This requires three key permissions, typically covering venue approval, fire safety clearance, and licensing for public screenings.

Based on the response we got from the local population, the idea was that we would use the data to assess whether that place was a good candidate for installing a permanent cinema later on. For example, we’ve done trials in 8 locations in Chhattisgarh and now they all want us to set up a fixed cinema hall.

Our permanent installations largely mimic the infrastructure of our mobile models with a few key differences. For example, the seats we use are modern recliners - basically the same as you’d get in a multiplex - which mean that we tend to charge upto ₹150-200 to make up for the higher quality experience (vs generally ₹50-100 in our mobile locations). The set up process requires a five-day period for full assembly into a functional theatre. Setting up a fixed unit also involves obtaining four essential permissions, which typically include local municipal approvals, fire safety clearances, electrical compliance, and public screening licenses. This setup is has also been popular for Corporate and PSU project sites in remote areas, where a significant workforce is stationed, often without their families, and where entertainment options are extremely limited.

Until we get in a big infusion of funds we have to be judicious about where we make our permanent investments. We simply cannot set up in all the places that want us to set up. When I told you about those 428 viable sites, before COVID our mobile units had screened at least one film in 500 locations, catering to over 1.5 million total attendees. Now we’re at over 650 locations and over 3 million total viewers. We know the demand is there.

In a lot of cases our temporary theatres have supported the outreach efforts of governments, NGOs, and corporates - which brings in additional revenue. So from an economic standpoint too there’s a clear business case.

And on the fixed front? What have you learned so far? You mentioned that you’re looking to tie up with franchise partners for this - who would be the right kinds of partners?

Look, in India, especially in Tier-3 and rural India, there aren’t that many opportunities for formal employment, especially ones which are considered safe, organised, and aspirational. When we were studying the interiors of India, we saw the popularity of the ‘rural-franchise’ model which is commonly used by the big FMCG players like HUL, P&G, Patanjali etc. This model sits at the heart of the distributor-dealer network that these big consumer companies use to reach small towns and villages.

Essentially, local entrepreneurs become the exclusive distributors/dealers for a specific territory. They invest their own capital to stock inventory, set up storage, and hire local staff. The FMCG company provides training, marketing support, and standard operating procedures. They get market penetration without direct investment while their local partners keep the lion’s share of the revenue. It works because the local population tends to trust people from their own community over any stranger from some big corporation. These networks create a lot of opportunities for local employment and are a big boost to the local economy.

For us too, these local entrepreneurs from Tier 3, Tier 4, Tier 5 India are our ideal partners. Often, like we found in UP for example, it’s the same trusted person or family who runs all the major businesses in one locality. We’re looking to work with similarly ambitious individuals who are serious about doing business the right way, and serious about doing film exhibition the right way.

For them to set up a PictureTime theatre would require less than a crore of investment. One theatre would allow them to earn ₹60-80 lakh in annual revenue, including ticket sales, advertising, sponsorship, food and beverage sales. They can expect monthly profits ranging from ₹1-2 lakhs on average, though this varies significantly - sometimes dropping to ₹70-80,000 during slow periods, and spiking to ₹3-4 lakhs during big film releases. The ROI we’ve calculated is around 3-4 years, which stands up well when compared with other common businesses like an electronic shop (~₹2 crore investment), clothes retail chain (₹2.5-₹3 crores), and government agency petrol pump (~₹5-₹6 crores).

Plus, we’ve found that there’s a lot of local pride with owning a cinema theatre. It’s a ‘clean’ business - not a liquor shop or cigarette shop or a junk food stall. There’s prestige attached to it because of how much joy it gives to people in a community. These days we get 10-15 queries from potential partners every week. It’s important to be careful here, though, because we’ve seen other companies trying to replicate our model who’ve found themselves in trouble because they’ve rushed into partnerships with the wrong parties.

At the current moment we’re confident we have the makings of a great franchise business because we’ve been patient enough to first get the nuts and bolts in the right place.

You also touched on Defence - that must be a full circle moment for you, being able to set up permanent screens in army cantonments having grown up watching films in the open air amphitheatres with your father?

Definitely. Defence is shaping up to be an important vertical for us. What people might not realise is that recreation is an important aspect at any army base. It’s important for the spirit to relax in the down time. In the old days, when I used to watch films along with my father while he was still serving duty, it was never the latest movies. It was always reruns of movies that were 2-3 years old. Even today the newest films only reach army personnel a few weeks after release, because of archaic conditions and costs imposed by distributors.

So our pitch was that we would be able to supply a high-quality film-watching experience to cantonments, and not only that, we would get them the latest films on the first day, and also provide multiple films at the same time. At the moment we have 14 screens in the pipeline, and at any of our sites there’s a lot of happiness from our armed forces and their families.

The way this arrangement works is we put up the costs of installing a PictureTime theatre. The Ministry of Defence will give us a small ‘subscription’ fee to set up, generally depending on the number of seats installed. And then we charge for the price of tickets (generally not more than ₹50). It’s an upgrade on the old way of doing this, in both price and quality of experience.

All of that is so interesting, because someone without your background would have never even known that this was a “problem” worth solving. One thing I wanted to touch on - you had alluded earlier to some ‘major wins’ on the regulatory side of things. What did you mean there?

Remember earlier when I said that along with conceptualising our mobile theatre solution in 2015, we had also simultaneously started a fight - or rather a ‘mission’ - to convince state and central officials that we needed a new regulatory framework around film exhibition in India. Essentially we wanted to make the case that theatre solutions like ours - especially the fixed kind - shouldn’t be required to comply with the same quantum of rules, permissions, licenses and regulations as multiplexes. For example, conditions regarding plumbing or sewage treatment requirements have no relevance to our theatres. It made no sense, to compare our inflatable theatres with a heavy-duty multiplex on a legislative basis.

While we began the process of applying for our patents around 2016-17, we started elevating the regulatory conversation too with various state chief ministers as well as the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MOIB). Everyone was at least receptive to our arguments, because they saw that our goal was basically to spread joy, to take the film industry into the hinterlands, and to contribute to the local economies.

It all changed with the appointment of Mr. Apurva Chandra, who was then the Secretary of Information and Broadcasting at the Government of India [and is now Principal Advisor to the Ministry of Defence]. He came and visited our theatre in Ladakh, and he asked me how he could help spread our solution further, because the government had by then earmarked media and entertainment as a ‘champion’ sector that could do very well for India if promoted properly. I requested if he could write a letter to all the state chief ministers, to tell them our product was legitimate, so we could then get a single window clearance for approval of our theatres. Along with Mr. Armstrong Pame, who was a Director at the MOIB - particularly looking after Films - they were both immensely helpful to our cause.

He wrote this letter of recommendation to the chief secretaries of all Indian states and union territories, telling them about our product, how we were providing high quality but low cost solution for cinema fans, how we would help the government increase screen density in India, and how even the governments would benefit from the outreach capabilities of our theatres. He recommended them to support us with NOC certificates, land leasing, other help. And many state officials have been receptive towards us following that. Some, particularly in the North-East, have even committed funds to partly sponsor the installation of screens in their districts with no cinema availability.

On our end, we continued meeting government officials at every point. We’ve kept on saying that our old Exhibition policies and guidelines are holding the sector back, that they need to be changed. I’ve personally served on several committees (including during WAVES along with top government and industry officials and representatives) on increasing screen density in India. There are now many parts of the official machinery that are seeing the world the same way we do. As of last year it looks like this change is on its way. The Centre is working on a new policy framework that will be recommended to the States. Then it’s on them to decide whether to take up or not.

But what exactly are the changes you’re trying to see?

Essentially the main things we’ve been fighting for, and the main recommendations we’ve made to the Centre, are:

With respect to licensing and regulations - to recognise a new category of cinema halls i.e. Fixed Digital Movie Theatres, which are not made of Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC) like regular cinemas, where licensing and NOC can be issued on an expedited basis in a few days (vs years).

To enable the growth of cinema infrastructure in small towns - for each state to formulate a policy that includes financial support for the setting up of affordable single screen theatres, including certain requirements (eg: to screen regional and local language films, to cap tickets at ₹150-200 etc) and standards (eg: Dolby 5.1, air conditioning etc), along with proposed government concessions (eg: capital subsidies, temporary GST exemptions etc). The idea is to get states that currently only have policies for multiplexes to revise and revisit their mandate to include smaller, economically viable cinema models.