The Infinite Almanac of Writing Wisdom

or The Timeless Treasury of Writing Tips and Techniques (by Tigerfeathers)

Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 343 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece, a 35,000-word epic on the story of Pixxel, one of India's foremost spacetech mavericks.

If you managed to *finish* our last piece in one sitting - congratulations. It means you effectively scrolled the distance from Bombay to Bangalore.

For everyone else, the scenic route is this way👇

Friends, if you are still making it through our last essay, don’t worry. We’re not adding to your load this time around.

This week is more of a palate cleanser between the Pixxel piece, and our next featured edition on the story of ‘Indian Fintech’s Golden Child’🍯. That one should be out in the next couple of weeks, followed by the second edition of our year-end review. I’m also working on the story of Mumbai’s leading hospitality company, but that might have to wait till early next year.

Right, so what’s on the menu this time around? Two quick notes on what you’re reading, and why it exists.

1. The Infinite Almanac of Writing Wisdom

Since launching Tigerfeathers in the summer of 2020, I’ve rearranged much of my life to accommodate this newsletter at the centre of my professional solar system. Along the way I’ve collected countless nuggets of wisdom on the creative process; on the tenets of good writing; on building an audience and the realities of the creator economy; on idea generation and storytelling; on research, editing and distribution; and so on.

Much of this has been so far marooned across an archipelago of documents, files, notebooks, and notes folders on my phone and laptop. This is my attempt to compile the best bits from that collection in one place.

Some of this is from books, tweets, newsletters and podcasts. Some of it I’ve learned by doing. Some of these are just examples of great prose from my favourite authors. Some of this isn’t even writing advice - they’re maxims on company building or creativity that I’ve repurposed to suit my own agenda.

There are 100 entries on the initial version of this list. We’ll keep adding to it in ‘drops’ of 25 every couple of months. You can think of this as an infinite journal on writing, one that we’ll continue to maintain as long as we’re still working on things here at Tigerfeathers. The goal is that this eventually becomes the most valuable, richly populated resource on the creative process that you can find anywhere on the Internet.

2. Okay but why does it exist

As longtime Tigerfeathers readers know, we've been trying-and-testing our way to building an independent internet-first media company based around the written word for four years now. That’s meant a lot of experiments with types of content and potential business models (both of which are likely to continue).

If you’ve read our stuff this year, you know that we’ve been partnering with sponsors for each edition of the newsletter. In fact, we’ve been very fortunate to work with some of our favourite start ups and investors, who’ve helped to keep our writing free for anyone to access. That will always be the case.

This piece, however, was intended to be a one-time experiment with a paywall. It’s been in the drafts since June. This was the concept - an initial compilation of 100 entries to this ‘diary’, 20 of which would be free to access, and the rest behind a paywall, with a one time payment for lifetime access to the article. The idea was that every couple of months we would scale the pricing up as we added to the list, turning this into a perpetually refreshed and perennially valuable resource. (It’s not an entirely original idea - David Senra from the Founders podcast has been doing something similar with his Founders Notes).

But we’ve abandoned that plan.

Why? Because in May of this year, our newsletter provider - Substack - effectively cut off Indian writers from running paid publications when their payment provider Stripe ‘pulled back’ from the Indian domestic market. We've reached out to the Substack team multiple times since then to ask when this is going to be resolved. They’ve responded each time with the customer service equivalent of a shrug emoji.

The bottom line - I got tired of watching this gather dust in our drafts folder, so we published it on Twitter earlier this week, with no plans for an email edition. As another indication that we have no idea what we’re doing, it's gotten more shares and responses in its first three days than anything else we've done this year.

So here it is, delivered straight to your inbox.

You don’t have to read this in one go. The idea is to scroll through this list if you find yourself stuck or struggling for inspiration, if you’re bored, if you’re just starting out, or if you have a bunch of time on your hands and you’re looking for something that’ll make your brain feel warm and fuzzy.

If you know someone who might find this useful, feel free to spread the word.

And if someone shared this with you and you enjoyed reading, get more of the same stuff here👇

1. David Fincher on introductions

“The first scene in a movie should teach the audience how to watch it.”

2. Anne Lamott on taking it one step at a time

“E.L. Doctorow said once said that 'Writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.' You don't have to see where you're going, you don't have to see your destination or everything you will pass along the way. You just have to see two or three feet ahead of you. This is right up there with the best advice on writing, or life, I have ever heard.”

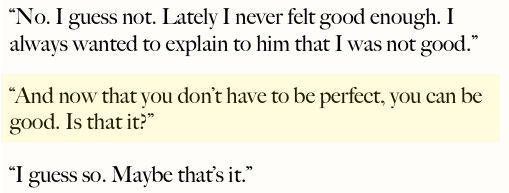

3. John Steinbeck on ditching perfection (via East of Eden)

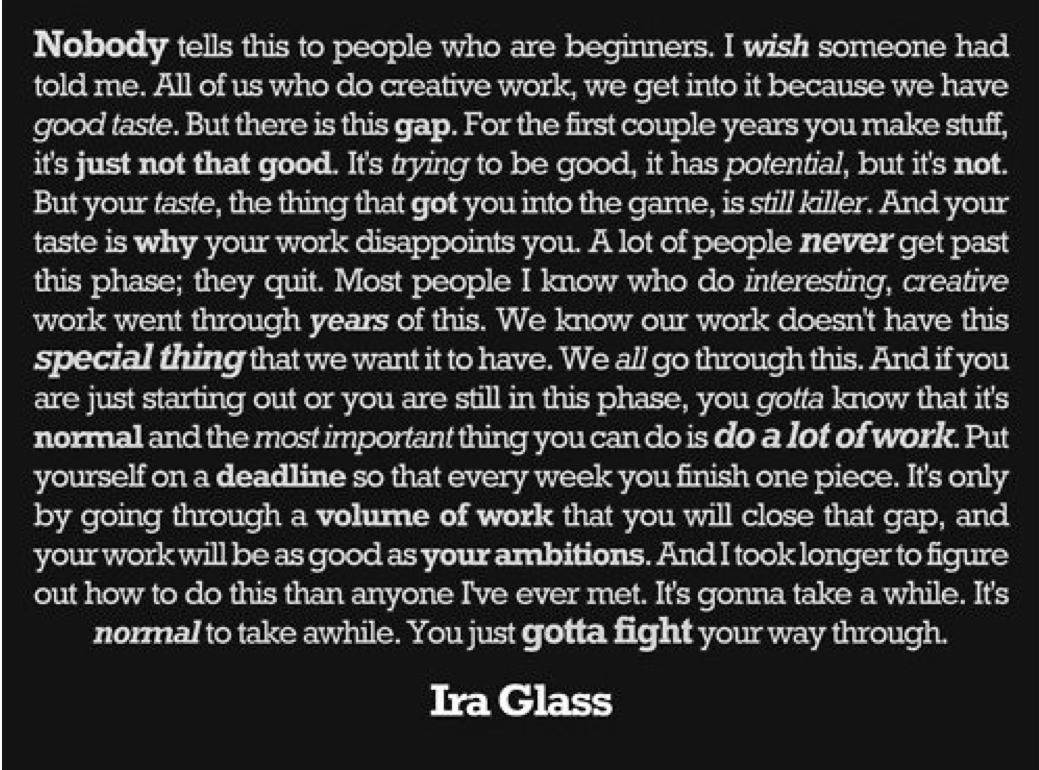

4. Ira Glass on ‘The Taste Gap’

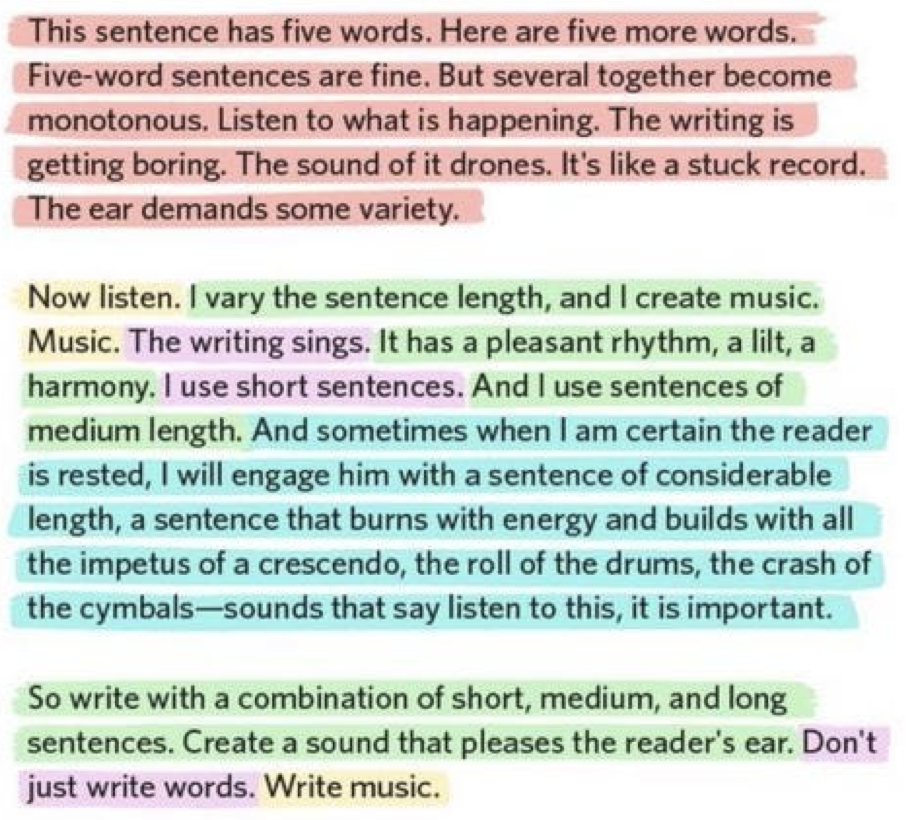

5. Gary Provost on ‘writing music’

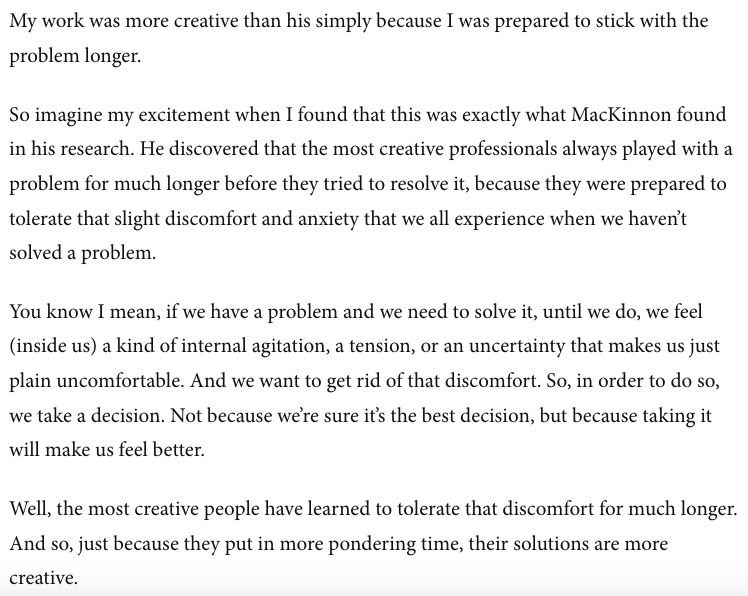

6. John Cleese on ‘Maximum Pondering Time’

7. Ed Catmull on shitty first drafts

8. Steph Ango on why we need concise writing

9. Jeremy Giffon on the online writing opportunity (h/t David Perell)

10. Eugen Herrigel on letting it come easy (via Zen in the Art of Archery)

11. Ryan Holiday on doing the work

“Self-belief is overrated. Generate evidence.”

12. The Bhagavad Gita on decoupling effort from reward

“You are entitled only to the labour, never to its fruits.”

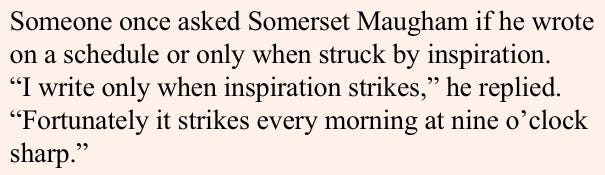

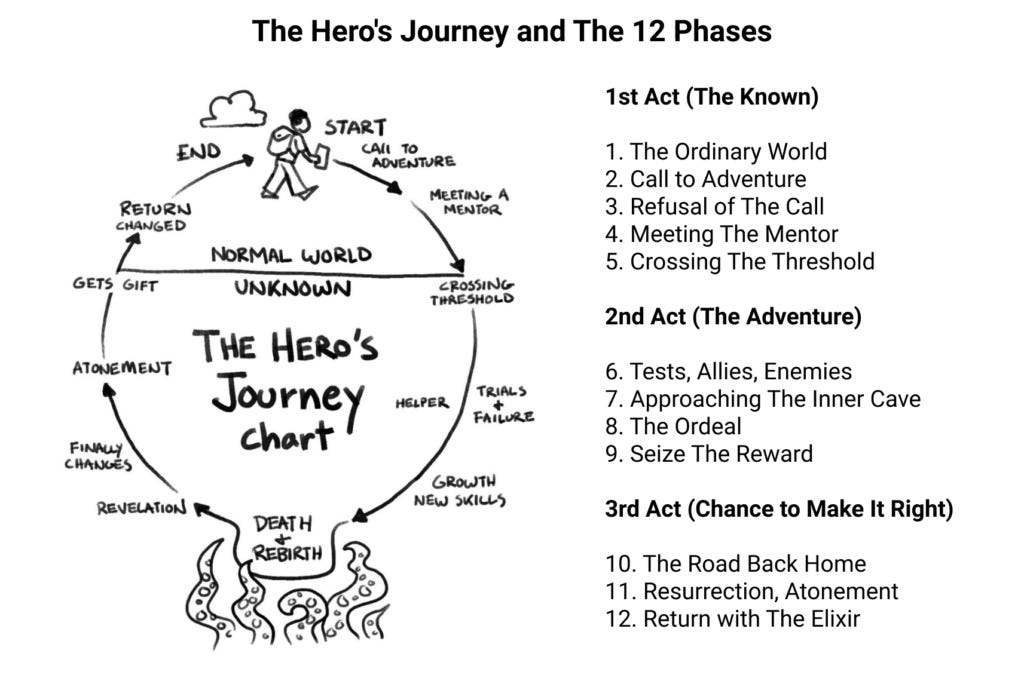

13. William Somerset Maugham on routine

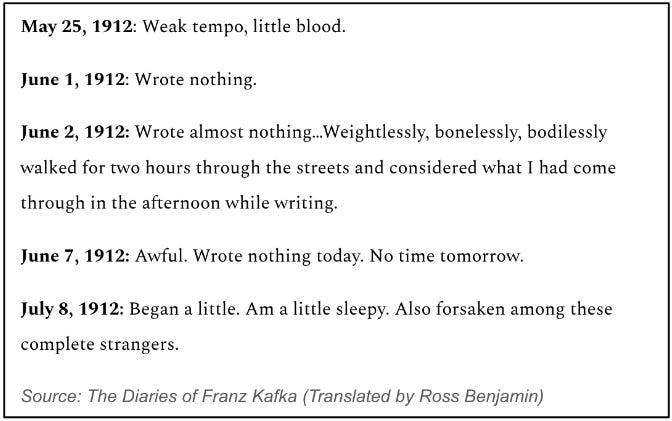

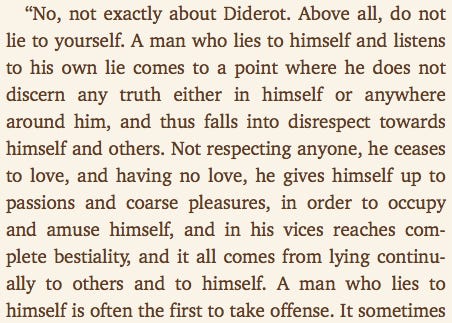

14. Franz Kafka on...relatability (h/t SatPost by Trung Phan)

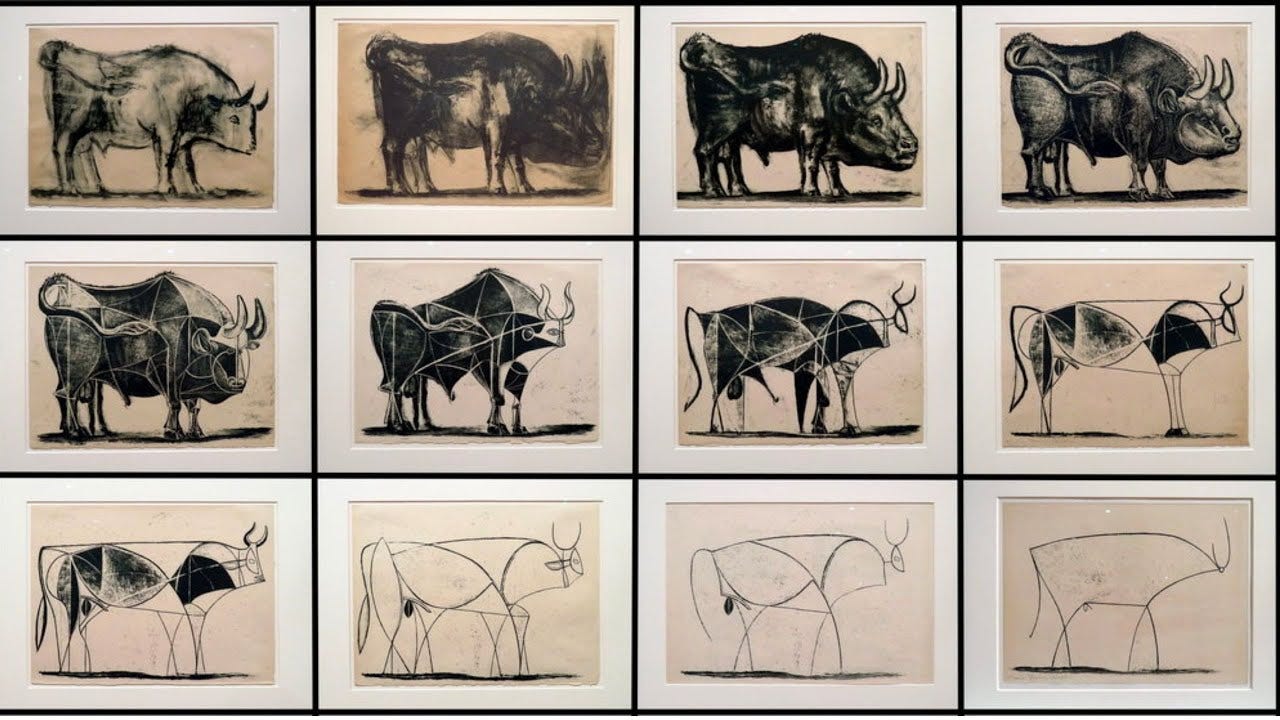

15. David Foster Wallace on just doing the thing (via Infinite Jest)

16. Neil Postman on metaphors

“A metaphor is not an ornament. It is an organ of perception. Through metaphors, we see the world as one thing or another.”

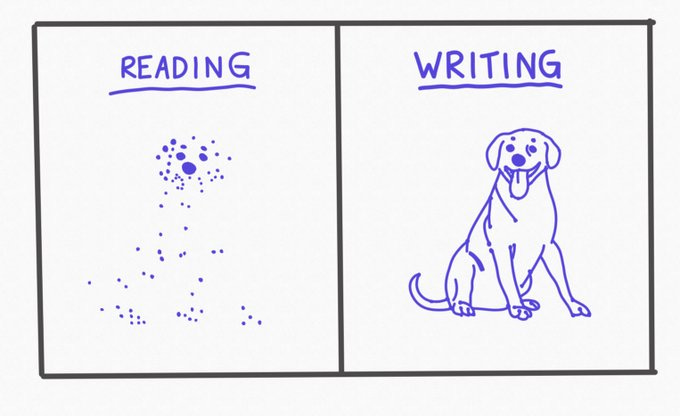

17. Peter Mendelsund on reading as a co-production (via Derek Thompson’s Hit Makers)

“As Peter Mendelsund wrote in What We See When We Read, a book is a coproduction. A reader both performs the book and attends the performance. She is conductor, orchestra, and audience. A book, whether nonfiction or fiction, is an “invitation to daydream.”

18. Muriel Rukeyser on the universe

“The universe is made of stories, not atoms”

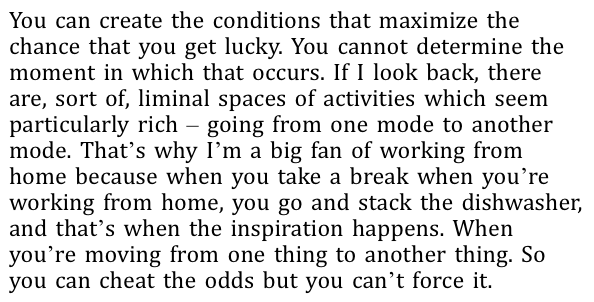

19. Rory Sutherland on choosing moments of inspiration

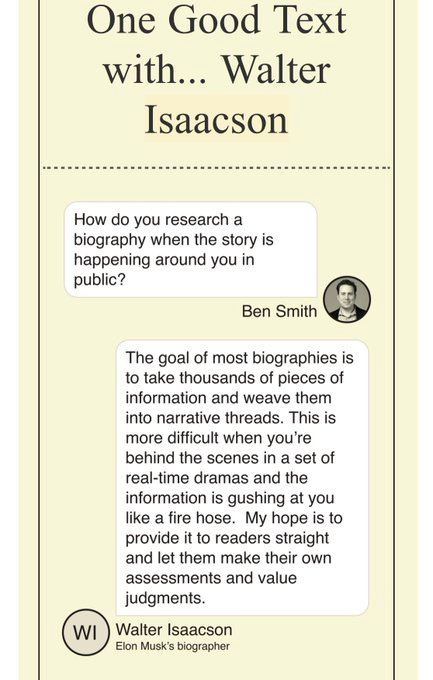

20. Walter Isaacson on ‘keeping it chronological’

21. John Le Carre on the importance of conflict in storytelling (h/t Jim O'Shaughnessy)

22. H.G. Wells on editing

“No passion in the world is equal to the passion to alter someone else’s draft.”

23. Marshall McLuhan on education v/s entertainment

“Anyone who tries to make a distinction between education and entertainment doesn't know the first thing about either.”

24. Brian Eno on deadlines (h/t SatPost by Trung Phan)

25. On ‘The Numbers You Don’t See’

26. Naval Ravikant on writing great books

“To write a great book, you must first become the book.”

27. Walter Isaacson on writing biographies

28. Kurt Vonnegut on character motivations

"Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water."

29. Antidotes to Fear of Death by Rebecca Elson

“Sometimes as an antidote

To fear of death,

I eat the stars.

Those nights, lying on my back,

I suck them from the quenching dark

Til they are all, all inside me,

Pepper hot and sharp.

Sometimes, instead, I stir myself

Into a universe still young,

Still warm as blood:

No outer space, just space,

The light of all the not yet stars

Drifting like a bright mist,

And all of us, and everything

Already there

But unconstrained by form.

And sometime it’s enough

To lie down here on earth

Beside our long ancestral bones:

To walk across the cobble fields

Of our discarded skulls,

Each like a treasure, like a chrysalis,

Thinking: whatever left these husks

Flew off on bright wings.”

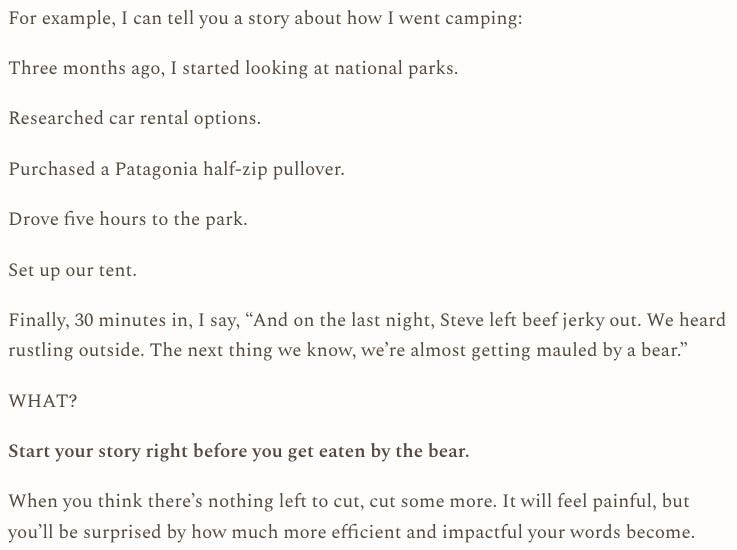

30. Wes Kao on getting rid of ‘non-essential backstory’

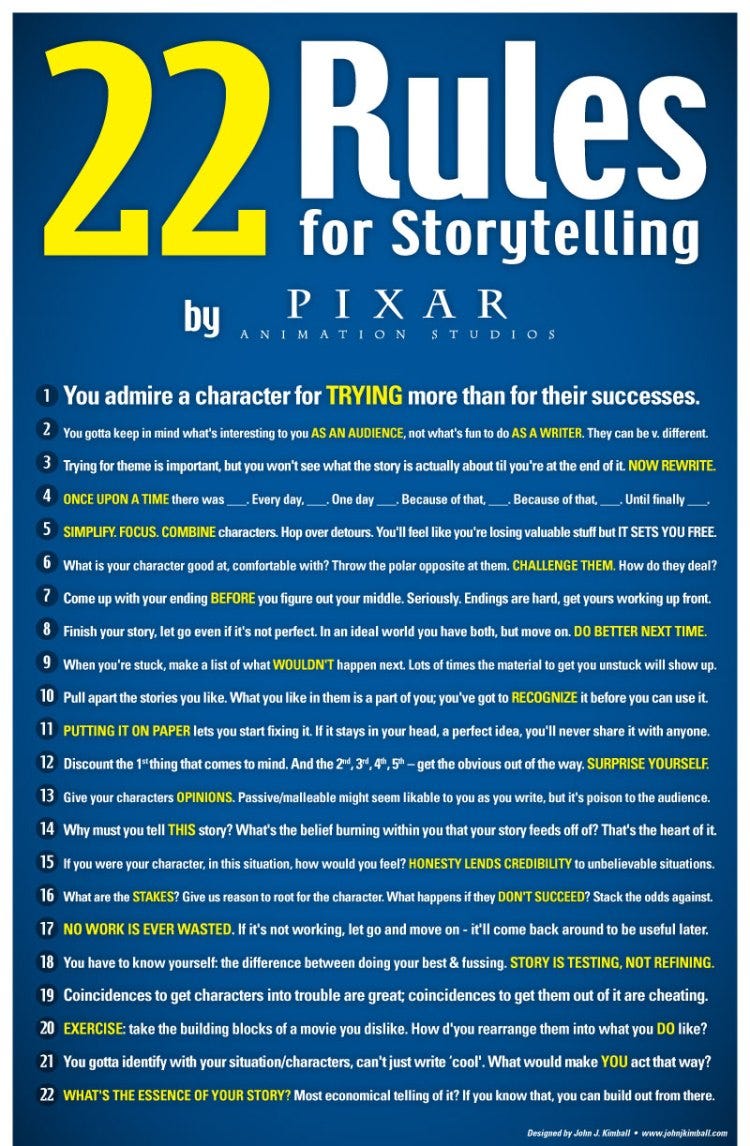

31. Pixar’s 22 Rules for Storytelling

32. Isaac Babel on punctuation (via George Saunders)

“Russian short story master Isaac Babel put it, “no iron spike can pierce a human heart as icily as a period in the right place.”

33. Brandon Sanderson’s general advice for new writers

Learn to turn off your internal editor.

Don’t try to write too many viewpoints at first.

Remember to pick a single, solid conflict to be your over-arching story conflict.

Try to blend familiar ideas with those that are original.

Focus on CONCRETE details.

Learn the market.

Finally, don’t give up!

34. C. S. Lewis on why we write

“We do not write in order to be understood; we write in order to understand.”

35. Pride and Prejudice - Jane Austen

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

36. David Ogilvy on the need to repeat your message

"You aren't advertising to a standing army. You're advertising to a moving parade."

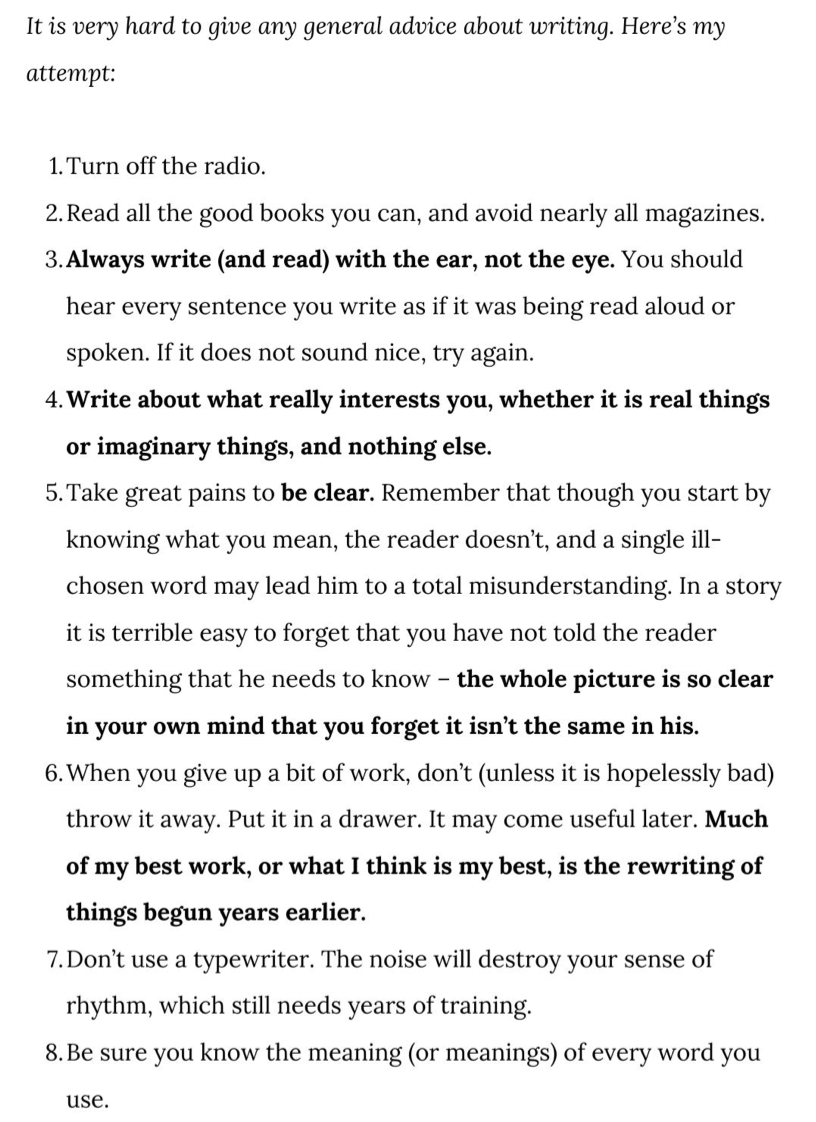

37. C. S. Lewis’ letter to a young writer (h/t Nathan Baugh)

38. On who you should write for

Write the piece that you would love to read, safe in the assumption that there are probably millions of people on the Internet who love the same stuff that you do.

39. Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules of Writing

“These are rules I’ve picked up along the way to help me remain invisible when I’m writing a book, to help me show rather than tell what’s taking place in the story. If you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after, and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over.”

Never open a book with weather.

If it’s only to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the weather, you don’t want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people. There are exceptions. If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways to describe ice and snow than an Eskimo, you can do all the weather reporting you want.Avoid prologues.

They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. But these are ordinarily found in nonfiction. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want.There is a prologue in John Steinbeck’s Sweet Thursday, but it’s O.K. because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: “I like a lot of talk in a book and I don’t like to have nobody tell me what the guy that’s talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks. . . . figure out what the guy’s thinking from what he says. I like some description but not too much of that. . . . Sometimes I want a book to break loose with a bunch of hooptedoodle. . . . Spin up some pretty words maybe or sing a little song with language. That’s nice. But I wish it was set aside so I don’t have to read it. I don’t want hooptedoodle to get mixed up with the story.”

Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue.

The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But said is far less intrusive than grumbled, gasped, cautioned, lied. I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with “she asseverated,” and had to stop reading to get the dictionary.Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said” …

…he admonished gravely. To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange. I have a character in one of my books tell how she used to write historical romances “full of rape and adverbs.”Keep your exclamation points under control.

You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful.Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose.”

This rule doesn’t require an explanation. I have noticed that writers who use “suddenly” tend to exercise less control in the application of exclamation points.Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

Once you start spelling words in dialogue phonetically and loading the page with apostrophes, you won’t be able to stop. Notice the way Annie Proulx captures the flavor of Wyoming voices in her book of short stories Close Range.Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

Which Steinbeck covered. In Ernest Hemingway’s Hills Like White Elephants what do the “American and the girl with him” look like? “She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.” That’s the only reference to a physical description in the story, and yet we see the couple and know them by their tones of voice, with not one adverb in sight.Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

Unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language or write landscapes in the style of Jim Harrison. But even if you’re good at it, you don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill.And finally:

Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

A rule that came to mind in 1983. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue.My most important rule is one that sums up the 10.

If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.

40. David Perell on inputs v/s outputs

41. The Hero’s Journey - Joseph Campbell

42. The Brothers Karamazov - Fyodor Dostoyevsky

43. Picasso’s Bull - editing to find the essence of your subject

44. Snoop Dogg on J Dilla

“One thing about people who are ahead of their time, they don’t even know they’re ahead of their time. They’re just playing the game…they don’t look at their highlights to see what kind of stats they got, cause they so busy putting up points. They so busy being great.”

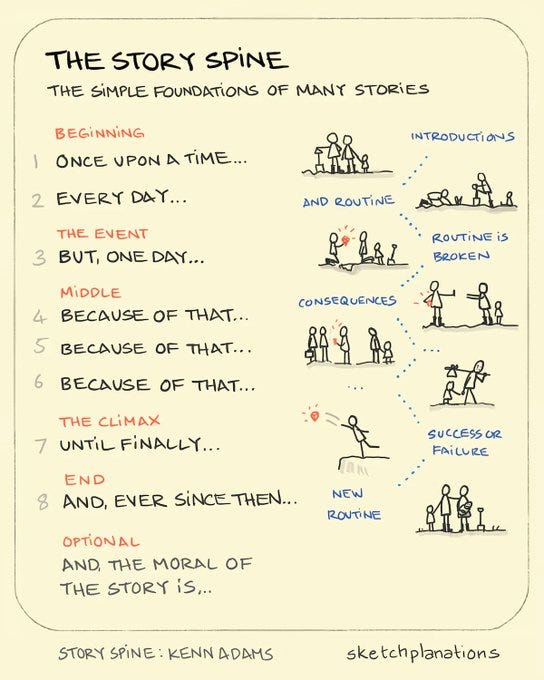

45. ‘The Story Spine’ by Kenn Adams

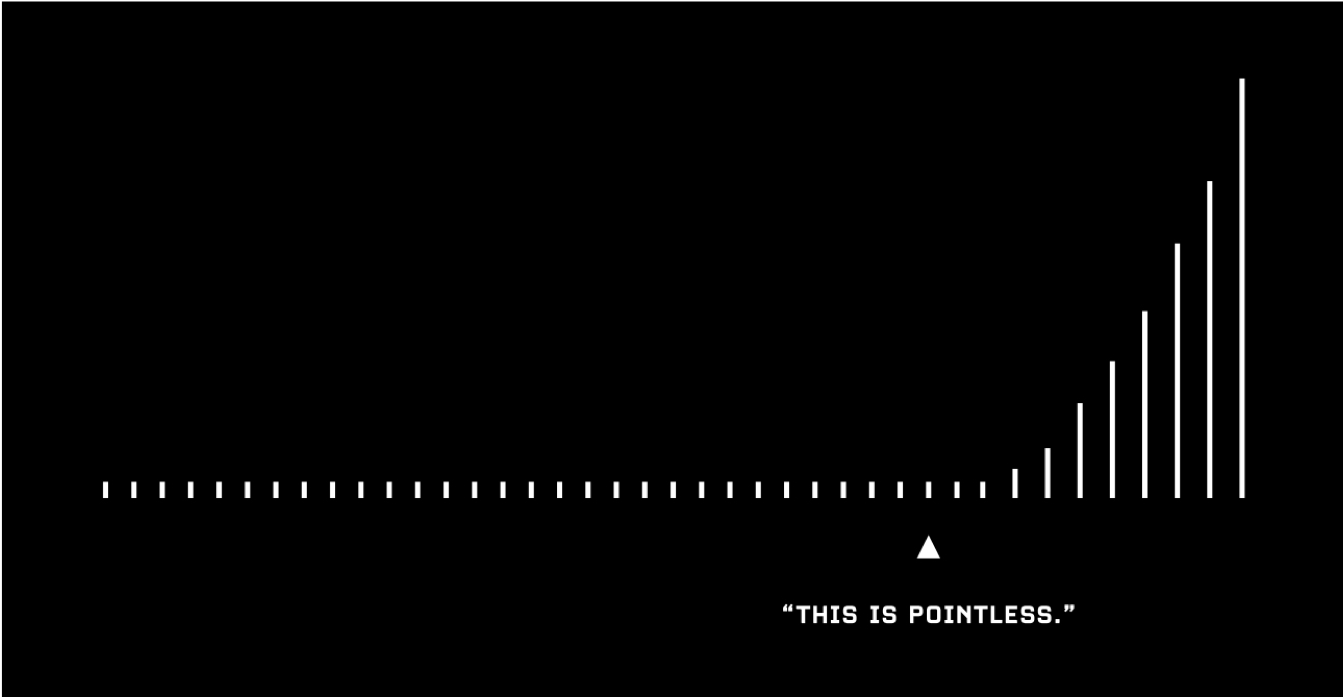

46. Jack Butcher on the magic of compounding

47. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy - Douglas Adams

“For instance, on the planet Earth, man had always assumed that he was more intelligent than dolphins because he had achieved so much—the wheel, New York, wars and so on—whilst all the dolphins had ever done was muck about in the water having a good time. But conversely, the dolphins had always believed that they were far more intelligent than man—for precisely the same reasons.”

48. Seth Godin on nurturing your ‘smallest viable audience’

“Seek the smallest viable audience. Make it for someone, not everyone.”

"I think being noticed is way overrated. It is enormously unimportant. You meed to be trusted by the smallest viable audience. You need to give the smallest viable audience something to talk about."

“Marketing is about telling a true story that resonates with your smallest viable audience. A story that they want to hear, that causes them to take action and tell their friends.”

“Instead of trying to reach everyone, we should seek to reach the smallest viable audience, and delight them so thoughtfully and fully that they tell others.”

Seek to assemble “the smallest group that could possibly sustain you in your work.”

“The goal isn’t to maximize your social media numbers. The goal is to be known to the smallest viable audience.”

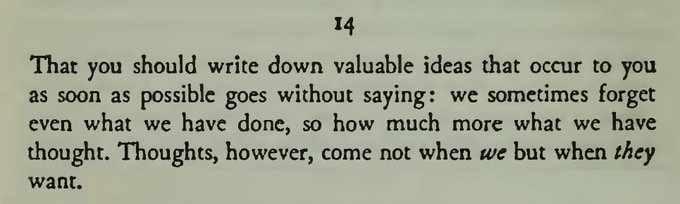

49. Schopenhauer on writing it down (h/t @DylanoA4)

50. Snow Crash - Neal Stephenson

“When you are wrestling for possession of a sword, the man with the handle always wins.”

51. Chuck Klosterman on exclamation marks (via Eating The Dinosaur)

“F. Scott Fitzgerald believed inserting exclamation points was the literary equivalent of an author laughing at his own jokes, but that's not the case in the modern age; now, the exclamation point signifies creative confusion. All it illustrates is that even the writer can't tell if what they're creating is supposed to be meaningful, frivolous, or cruel. It's an attempt to insert humor where none exists, on the off chance that a potential reader will only be pleased if they suspect they're being entertained. Of course, the reader isn't really sure, either. They just want to know when they're supposed to pretend to be amused.”

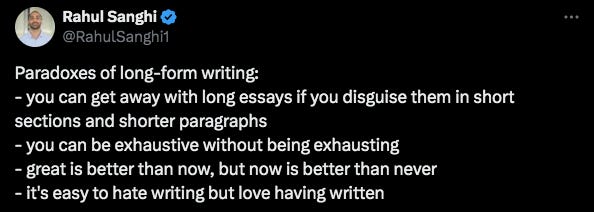

52. Paradoxes of long-form writing

53. Nic Pizzolatto (writer and director of True Detective) on elevating your story

“Nobody was going to let me make a TV series that was just about two men riding around talking…so I put murder in there.”

54. Invisible Cities - Italo Calvino

“You reach a moment in life when, among the people you have known, the dead outnumber the living. And the mind refuses to accept more faces, more expressions: on every new face you encounter, it prints the old forms, for each one it finds the most suitable mask.”

55. Bookbear Express by Ava

“Writing gives shape to all time I spent reading”

56. Anthony Bourdain on savouring the ride

"The journey is part of the experience — an expression of the seriousness of one's intent. One doesn't take the A train to Mecca."

57. Jawaharlal Nehru on India

“India has known the innocence and insouciance of childhood, the passion and abandon of youth, and the ripe wisdom of maturity that comes from long experience of pain and pleasure; and over and over a gain she has renewed her childhood and youth and age”

58. Julian Shapiro on how to tell great stories

“Talented storytellers know something bad storytellers don't: storytelling is the art of strategically withholding information. Before you begin your story, you're supposed to decide which details to withhold until the end—to maximize suspense along the way.”

“Next, I noticed that the best storytellers take the hook methodology to an extreme: they intersperse many hooks throughout their narrative by continually raising questions without immediately answering them. When they finally get to the nail-biting answers, they then drag out the telling.”

“In other words, storytelling is not only the art of strategically withholding information, it’s also the art of time dilation.”

“The more I listened to vocal variation, the clearer it became that spoken storytelling is a form of music. You talk. Then faster. You go silent. You strike with fast staccato sentences. Without vocal rhythm and pauses, you're just a human wall of text.”

”Blowing your own mind entails being excited at moments of excitement, being shocked at moments of shock, and being wowed at moments of wonder. Listeners feed off this like sugar.”

“That's the feeling you need to transfer into your audience. They don't feel it in their bones unless it looks like you're feeling it first.”

59. David Perell and Jack Butcher on how to Build Your Creative Career

get going, then get good

proof of work on the Internet is shifting from credentials to output

it’s not about 10,000 hours it’s about 10,000 iterations

the world rewards people who are best at communicating ideas, not the people who have the best ideas

people will flock to you because of the scarcity of your perspective

60. Old Eastern adage on Enlightenment

“Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.”

61. Steven Pressfield on answering the call to create

“Our job in this life is not to shape ourselves into some ideal we imagine we ought to be, but to find out who we already are and become it.”

62. Susan Sontag on questions and answers

"The only interesting answers are those which destroy the questions"

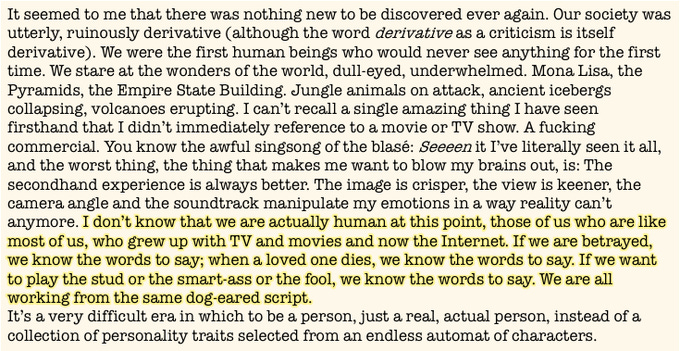

63. Jonathan Franzen on how TV is killing the novel (via How To Be Alone)

“I mourn the eclipse of the cultural authority that literature once possessed, and I rue the onset of an age so anxious that the pleasure of a text becomes difficult to sustain. I don’t suppose that many other people will give away their TVs. I’m not sure I’ll last long myself without buying a new one. But the first lesson reading teaches is how to be alone.”

64. Jerry Seinfeld on The Tim Ferris Show

Jerry Seinfeld:…It’s like you’ve got to treat your brain like a dog you just got. The mind is infinite in wisdom. The brain is a stupid, little dog that is easily trained. Do not confuse the mind with the brain. The brain is so easy to master. You just have to confine it. You confine it. And it’s done through repetition and systematization.

Tim Ferriss: So let’s talk about feedback in the experimental loop that you mentioned earlier, which was desk, stage; desk, stage; desk, stage. One form of feedback would be audience feedback, and I’m curious what other forms of feedback you have.

Jerry Seinfeld: There is no other feedback, if that means anything.

Tim Ferriss: Okay, got it.

Jerry Seinfeld: Well, okay. Here’s a little — a fine point of writing technique that I’ll pass along to you writers out there. Never talk to anyone about what you wrote that day, that day. You have to wait 24 hours to ever say anything to anyone about what you did, because you never want to take away that wonderful, happy feeling that you did that very difficult thing that you tried to do, that you accomplished it, you wrote. You sat down and down and wrote.

So if you say anything — it’s like the same reason — have you ever heard the thing like, you never tell people the name that you’re going to give the baby —

Tim Ferriss: Sure.

Jerry Seinfeld: — until it’s born? Because they’re going to react, and the reaction is going to have a color. And if you’ve decided that that’s going to be the baby’s name, you don’t want to know what anybody else thinks. I will always wait 24 hours before I say anything to anyone about what I wrote, so you want to preserve that good feeling. Because let’s say you write something and you love it. And then later on that day, you’re talking to someone, and you go, “Hey, what do you think of this idea?” Blah, blah, blah. And they don’t love it? Now that day feels like, “I guess that, that was a wasted effort.”

You always want to reward yourself. The key to writing, to being a good writer, is to treat yourself like a baby, very extremely nurturing and loving, and then switch over to Lou Gossett in Officer and a Gentleman and just be a harsh prick, a ball-busting son of a bitch, about, “That is just not good enough. That’s got to come out,” or “It’s got to be redone or thrown away.”

So flipping back and forth between those two brain quadrants is the key to writing. When you’re writing, you want to treat your brain like a toddler. It’s just all nurturing and loving and supportiveness. And then when you look at it the next day, you want to be just a hard-ass. And you switch back and forth.

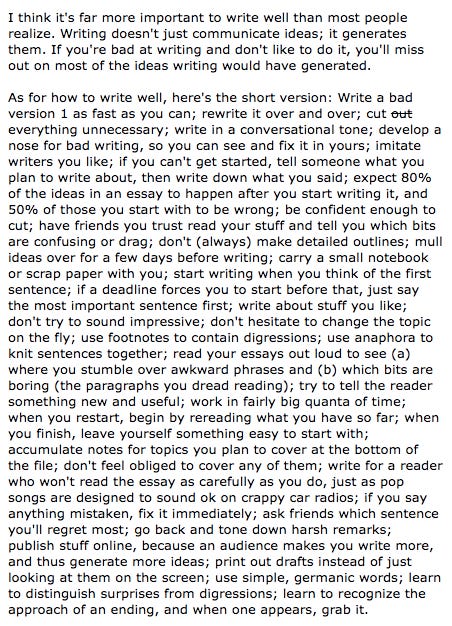

65. Paul Graham on writing as thinking

66. Rickson Gracie, Brazilian-Jiu Jitsu legend

"I am a shark, the ground is my ocean, and most people can't even swim."

67. Schopenhauer on the art of not reading (h/t @DylanoA4)

68. Joan Didion on 28 (h/t @DylanoA4)

69. E. B. White on writing for children (h/t Essayful)

70. 40 Ideas from How To Do Great Work by Paul Graham (compiled by David Senra)

1. Curiosity is the best guide.

2. Being prolific is underrated.

3. If you asked an oracle the secret to doing great work and the oracle replied with a single word, my bet would be on "curiosity."

4. Seek out the best colleagues.

5. Make something you yourself want.

6. If you're interested you're not astray.

7. Unfashionable problems are undervalued.

8. Curiosity and originality are closely related.

9. Your curiosity never lies, and it knows more than you do about what's worth paying attention to.

10. Never abandon the root node.

11. If you don't try to be the best you won't even be good.

12. Work with people you want to become like, because you will.

13. Interest will drive you to work harder than mere diligence ever could.

14. Great work happens by focusing consistently on something you're genuinely interested in.

15. Great work usually entails spending what would seem to most people an unreasonable amount of time on a problem.

16. We underestimate the cumulative effect of work. Writing a page a day doesn't sound like much, but if you do it every day you'll write a book a year. That's the key: consistency.

17. People think big ideas are answers, but often the real insight was in the question.

18. Something that grows exponentially can become so valuable that it's worth making an extraordinary effort to get it started.

19. Some of the biggest discoveries come from noticing connections between different fields.

20. It's a great thing to be rich in unanswered questions.

21. What are you excessively curious about — curious to a degree that would bore most other people? That's what you're looking for.

22. Boldly chase outlier ideas, even if other people aren't interested in them — in fact, especially if they aren't.

23. A field should become increasingly interesting as you learn more about it. If it doesn't, it's probably not for you.

24. One sign that you're suited for some kind of work is when you like even the parts that other people find tedious.

25. Ask yourself: Am I working on what I most want to work on?

26. The best ideas have implications in many different areas.

27. Original ideas don't come from trying to have original ideas. They come from trying to build or understand something slightly too difficult.

28. Great work often comes from returning to a question you first noticed years before and couldn't stop thinking about.

29. Big things start small. The initial versions of big things were often just experiments, or side projects, or talks, which then grew into something bigger.

30. You can't have a lot of good ideas without also having a lot of bad ones.

31. Begin by trying the simplest thing that could possibly work. Surprisingly often, it does.

32. Originality is the presence of new ideas, not the absence of old ones.

33. Husband your morale. It's the basis of everything when you're working on ambitious projects.

34. Avoid letting intermediaries come between you and your audience.

35. Don't marry someone who doesn't understand that you need to work, or sees your work as competition for your attention.

36. If you're ambitious, you need to work; it's almost like a medical condition

37. Seek out the people who increase your energy and avoid those who decrease it.

38. If you do anything well enough you'll make it prestigious.

39. What might seem to be merely the initial step — deciding what to work on — is in a sense the key to the whole game.

40. At each stage do whatever seems most interesting and gives you the best options for the future. I call this approach "staying upwind." This is how most people who've done great work seem to have done it.

71. John Boyd - to be or to do

“To be somebody or to do something. In life there is often a roll call. That’s when you will have to make a decision. To be or to do? Which way will you go?”

72. Cormac McCarthy on life (h/t @DylanoA4)

73. William Faulkner on making good art (h/t Essayful)

74. Carl Jung on facing your own soul (h/t @DylanoA4)

75. Michael Lewis on both sides of life

“If every day is sunny, the weather ceases to be interesting.”

76. Carl Jung on the creator economy (h/t @DylanoA4)

77. The Old Man and the Sea - Ernest Hemingway

“Now is no time to think of what you do not have. Think of what you can do with that there is.”

78. Gone Girl - Gillian Flynn

79. Charlie Munger on going niche

"It makes sense to load up on the very few good insights you have instead of pretending to know everything about everything at all times"

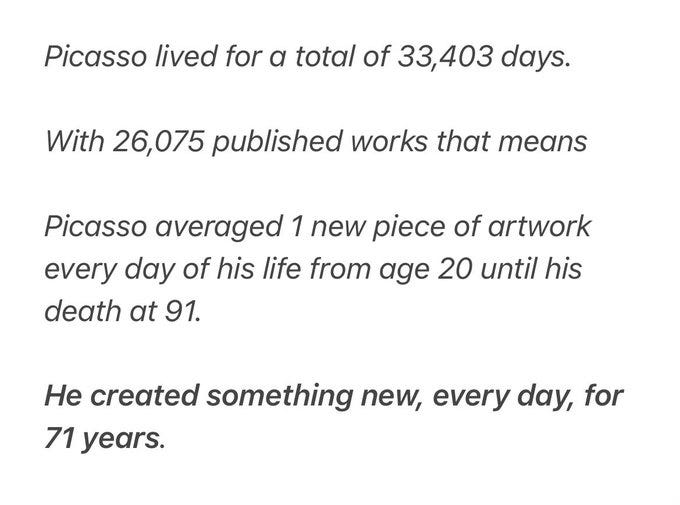

80. Picasso, the virtues of being prolific (h/t James Clear)

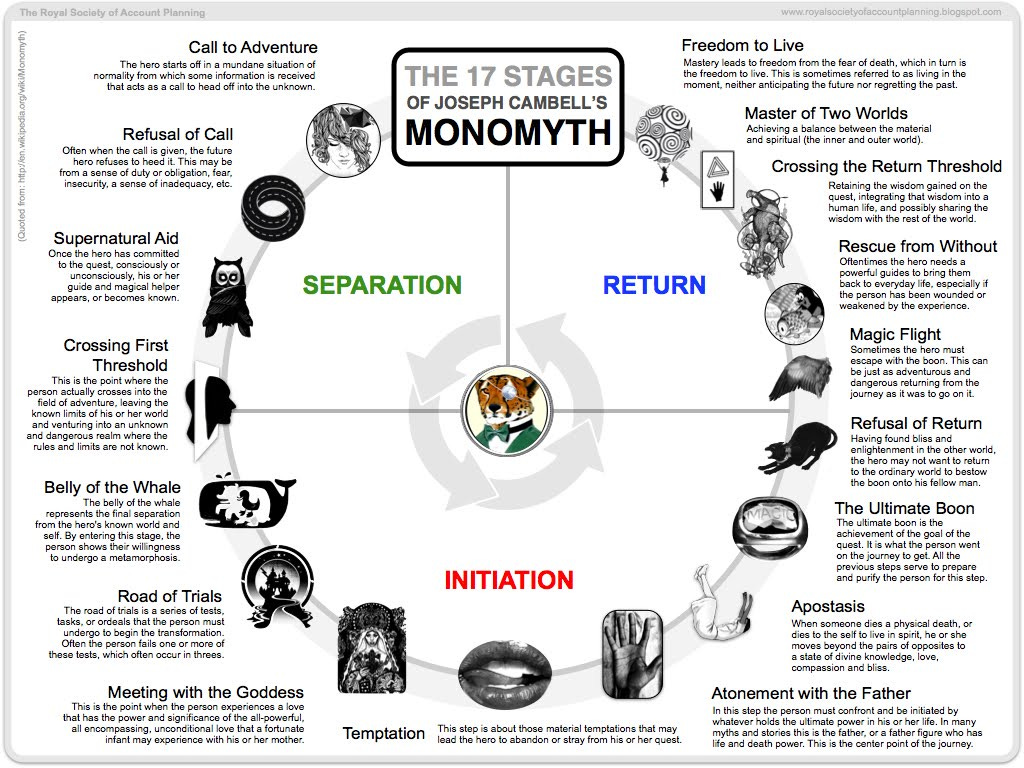

81. The 17 Stages of Joseph Campbell’s Monomyth

82. Ray Bradbury, on getting out of your own way (h/t David Perell)

"I don't believe in college for writers. It's dangerous. Professors are too opinionated, too snobbish, too intellectual, and the intellect is a great danger to creativity because you begin to rationalize and make up reasons for things instead of staying with your own basic truth — who you are, what you are, what you want to be.

I've had a sign over my typewriter for 25 years now which reads: "Don't think."

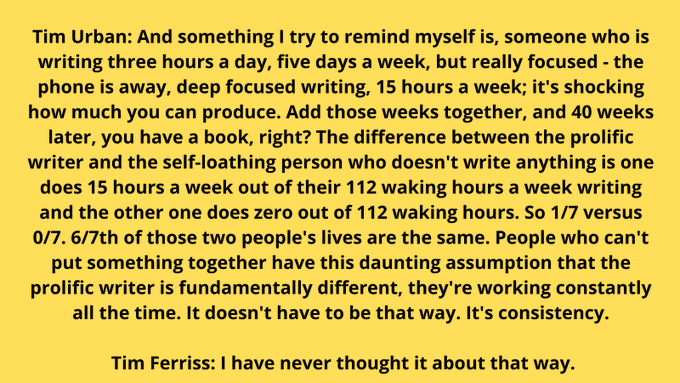

83. Tim Urban on consistency (h/t Dickie Bush)

84. Tim Urban on research (‘figuring out where the walls are’) and writing for yourself (‘stadiums full of me’s’) (h/t Tim Ferriss)

Tim Urban: Yeah. So, it’s pretty simple for me. First of all, I do this kind of weird thing where I assume that my audience is I picture like a stadium full of me. So, it’s narcistic fantasy. No, but it’s just – I’m just writing for – I’m writing the exact post that I would be thrilled to get.

So, I’m just – that’s my focus group right there, right in my head. And it’s easy because we’re all kind of special, unique people, except not really. There’s like 100,000 copies of each of you out there somewhere. And the truth is, if I just write for me, there are a lot of people that have my exact weird taste. I just know that. So, I start there with kind of like who am I writing for. That makes it easy. And so, with something like AI, if there’s a one through ten scale of how much you know about something, ten is world leading expert, and one has absolutely never heard of the term, I started at two or three on most stuff like most layman. I’m a layman about everything.

And so, then, I spend – just my curiosity is the driver. I pick topics I’m excited to dig into. And I’ll spend however long it takes. Sometimes, it’s one day. Sometimes, it’s three weeks. Sometimes, it’s three months. But I’ll take as long as I need to to learn enough to get me to maybe like a five or a six out of ten.

I’m not going to get a PhD. I’m not going to spend five years getting myself to an eight or nine. But I’m going to get myself to a six where I’m like I can answer, basically, any question a layman asks me. I can do a Q&A with an audience on this topic for 10 hours, and I’ll have a pretty good, solid answer to everything. Not that I know, necessarily, the truth of everything. But I know when the experts don’t know the truth, and they’re arguing. I know what the experts say about, basically, everything. So, I get myself to that level. And then, I think about so, experts have sometimes a hard time explaining because they haven’t been at a two in decades sometimes.

And they have this jargon. And they don’t remember what it’s like to be a two out of ten. I was there three weeks ago. I know exactly what my readers know about this. And I know exactly what – so, I just looked at the road I went down to get myself to a six. And I think about how could I do that road way more efficiently, if I could go do it again now? How could I do it in a much more fun way? And what’s a fun story I could tell to bring readers from the two to a six? And so, that’s my challenge then is to, basically, package the road I just went down for three weeks and make it an hour and a half package instead?

Tim Ferriss: Okay. Not surprisingly, I have some follow up questions. Let’s pick a subject. Have you written about crypto currency or blockchain?

Tim Urban: Not yet.

Tim Ferriss: Oh, perfect

Tim Urban: Highly requested topic.

Tim Ferriss: I’m sure it is. The reason I ask is that much like AI, I have seen dozens of people attempt to explain, without misrepresenting, crypto currency and blockchain 101 for the masses. And it seems like almost every single attempt has failed. If you were to take that assignment on, where would you start?

Tim Urban: So, I always start, I feel like, I’m blindfolded in a room. And I’m just trying to figure out where are even the walls here? Where is the furniture. I just want to start and understand what I even need to learn.

So, I want to get a picture of the topic. And then, I can start diving in, going down various rabbit holes. And, usually, going outside of the topic. A rabbit hole outside of the topic is procrastination. But it also, often, gives you even more context. You’ll find some metaphor out there that you end up bringing back. So, I’ll just read and read and watch You Tube videos all on the internet.

Tim Ferriss: How do you search? Reading, do you start at Wikipedia? Is that ground zero?

Tim Urban: Yeah. I’ll start at Wikipedia for just a basic foundation. Wikipedia is good at telling you where the walls are. Just letting you even understand the topic, in general. And letting you even understand the topic, in general. And Wikipedia has a lot of good knowledge on it. So, I’ll go there, and then, I’ll go to the bottom of Wikipedia and start clicking on the reference links. And I’ll usually Google blockchain PDF, and you end up finding all of these superbly boring journal articles. And then, I’ll go on You Tube. There are a lot of good people, smart teachers explaining stuff on You Tube.

They’re not going to explain the whole thing, usually. They’re going to explain one part. Maybe I realized that, to understand blockchain, you need to first go down three layers. You need to build a foundation that begins with understanding what encryption is. You need to understand how encryption works and public keys and private keys. That’s when you can start to, on top of that, build an understanding of what a ledger is that would be on these different computers and how it could possibly be secure. And by the time you get to blockchain, you’re like eight layers up. So, I’ll go find a You Tube video not on blockchain, but on encryption. And then, I’ll find a You Tube video explaining what ledgers are, in general.

I was reading about the history of ledgers and where they’re used it the world, and encryption and how it was invented and how its evolved. And you just keep doing this. And the reason it’s easy for me, this part, is because I’m super curious. So, the more I learn, the less icky the topic gets. When the topic gets un-icky, it starts to be super delicious, the opposite of icky. And then, I can’t read enough. And it’s so fun suddenly. I’m like I get it. And then, I just want to fill in the knowledge, and I want to watch a You Tube video I already know the answer to just to feel good about I already knew everything he’s saying.

this is great. But it solidifies it. And you hear seven different people articulate it in seven ways. And it just rounds out your understanding. And by the end, I start to be like I totally get this.

Tim Ferriss: I find a video on You Tube. So, last I checked, which was not recently, You Tube was the second largest search engine in the world. There’s a lot of great stuff. There’s also a lot of nonsense. How do you search? So, what are the terms? How do you sort them? How do you go about picking properly?

Tim Urban: Well, so, in Google, I will Google blockchain. Leave that in a window. Open a new window, and I’ll Google bitcoin. New window, Ethereum. New window, crypto currency. New window, decentralized systems crypto. New window, crypto currency is bullshit. New window, whatever. And I’ll just keep going.

And I’ll just think of anything. And then, each one of those windows I go back to, and I just hold down command, and I just click, click, click, click, click, click, and I have 10 tabs, 10 tabs, 10 tabs. And I just go and read everything. So, Google, again, I don’t have to discern. I don’t care if this [inaudible] article is going to be really useful or whether it’s going to be accurate because the beginning process is just if you read 70 articles that may or may not have validity to them, the total sum of them actually you start to understand what do we know as a species? Where are we all agreeing?

And then, where, clearly, a lot of people don’t know what they’re talking about. Or there’s this broad, this kind of dichotomy of a view in this one area. And there’s these people, and there’s these people. You Tube is kind of the same thing. I’ll just start watching without discerning. Again, if you’re a procrastinator, it’s fantastic because you don’t feel bad about just watching endlessly when it’s taking all of your time, and it’s not what you’re supposed to do, and it feels great. So, I’ll just watch. And then, of course, the sidebar starts to figure out – You Tube very quickly, and Google, will figure out what you’re doing. And then, You Tube will start to put all of the things on the side for me. Plus, you start to see names you trust.

Tim Ferriss: Make money in crypto currency in one week.

Tim Urban: Well, it’s funny, I’m just writing a post now on like, we won’t get into this, but like political stuff. And normally, my sidebar is like look how much of an idiot Trump is and his voters. And then, I’m now trying to – I was Googling all of these conservative things because I’m writing about both sides of stuff. And suddenly, the internet starts to indoctrinate me the other way. And they’re like look at this wise Trump voter embarrass this – and I look over, and I’m kind of like – and a couple of hours later, I’m like Trump is the best. So, You Tube figures out your angle, and it will start to kind of feed you stuff.

And then, there’s certain names you trust. Hank and John Green. I trust them. [Inaudible], I trust them. CGP Gray, I trust him. So, you’ll see certain names you trust. Minute Physics, great. So, there’s also that, and the same with Google, of course. I’ll trust certain sources more than others.

Tim Ferriss: And once you’ve ingested massive amounts of information, and you’ve established a basic map for the territory, what do you think are the tools or approaches, anything at all, that help you to be so good at teaching these subjects in the way that you present it or structure your pieces?

Tim Urban: Well, so, again, the starting point is I just went through this. And I teach myself. And I was bad at teaching myself because I didn’t know what I was doing. So, now, the experience of a learner is fresh in my head. So, that’s the first thing that’s helpful. But then, I always, basically, with almost any explainer post like that, I just zoom out. Helicopter up. If you’re looking at the land, and you see kind of like a beach, you don’t know what it is. Is this a huge lake? Is this a little beach? Does it curve around? I don’t know. That’s how I feel a lot of the articles on AI or crypto currency are.

And then, the author might have a full understanding, but they’re just describing the beach. So, you take a helicopter up, and you’re like okay, wait a second. This is a big river. And there’s a – and you go up further, and you’re like oh, no, this is kind of a tributary that goes into the ocean. And now, you’re kind of up where airplanes go and maybe even the International Space Station goes, and you’re like okay, this is actually what’s going on. So, I start there myself as a thinker and then, when I’m trying to explain, I’m just going to start there, which is why people make fun of me because I’ll write about three different things. And they all start at the big bang by the time I’m done with them.

I have to, basically, go back. But, sometimes, it’s helpful. By the time you get from the big bang to now, suddenly, we can see the whole coastline, and now, the beach suddenly makes sense. And I try to make it fun also because who wants to like – so many – the journal articles, the experts, they’re not writing to entertain.

And it’s just bad. It’s like textbooks and school where it’s so bad. They were so boring. Part of the reason I like You Tube is because people who end up with a lot of views on You Tube that are going to end up on my recommended thing, they have an eye for entertainment. So, I try to do the same thing as well.

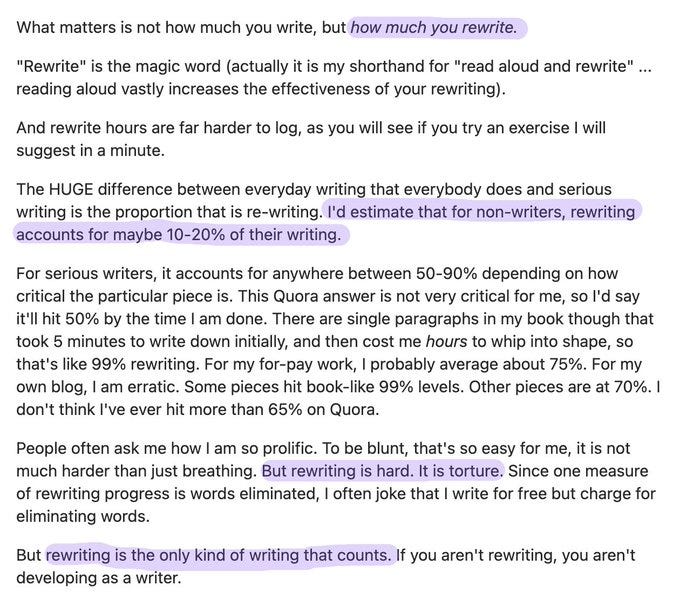

85. Venkatesh Rao on rewriting (h/t David Perell)

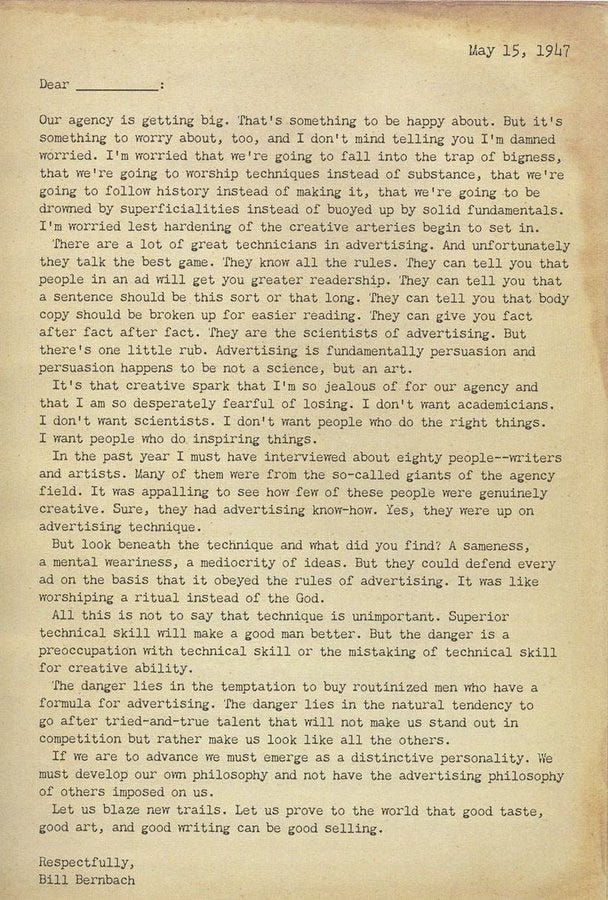

86. Bill Bernbach on advertising and creativity

87. Jason Fried on the writing class he’d like to teach

“During Q&A at a conference I spoke at a few years back, someone asked me “What’s your take on the true value of a university education?” I shared my general opinion (summary: great socially, but not realistic enough academically) and ended with a description of a course I’d like to see taught in college. In fact, I’d like to teach it.

It would be a writing course. Every assignment would be delivered in five versions: A three page version, a one page version, a three paragraph version, a one paragraph version, and a one sentence version.

I don’t care about the topic. I care about the editing. I care about the constant refinement and compression. I care about taking three pages and turning it one page. Then from one page into three paragraphs. Then from three paragraphs into one paragraph. And finally, from one paragraph into one perfectly distilled sentence.

Along the way you’d trade detail for brevity. Hopefully adding clarity at each point. This is important because I believe editing is an essential skill that is often overlooked and under appreciated. The future belongs to the best editors.

Each step requires asking “What’s really important?” That’s the most important question you can ask yourself about anything. The class would really be about answering that very question at each step of the way. Whittling it all down until all that’s left is the point.

Maybe one day.”

88. The Bell Jar - Sylvia Plath

“I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn't quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn't make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.”

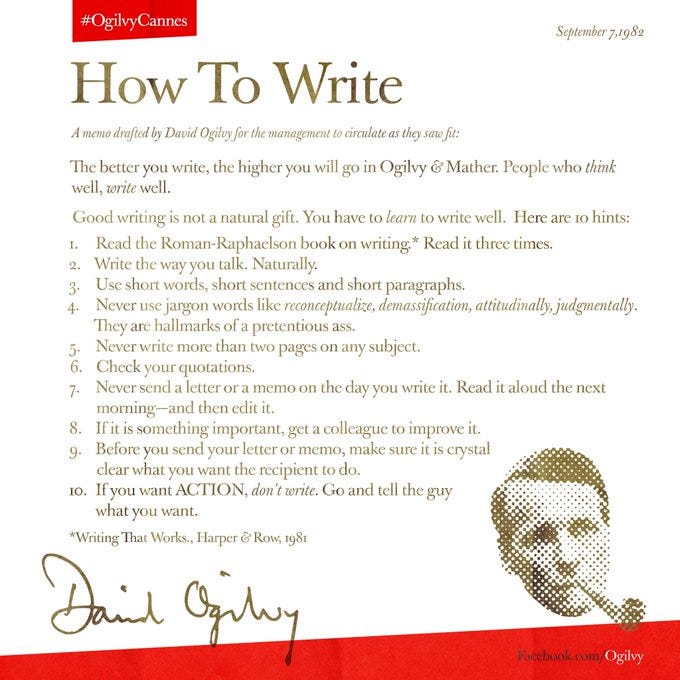

89. How To Write by David Ogilvy

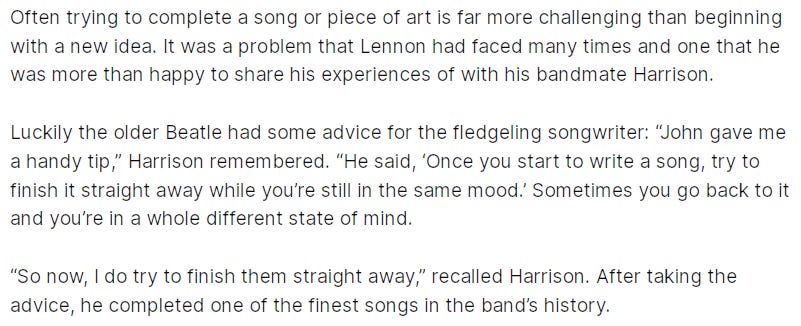

90. Advice on songwriting from John Lennon to George Harrison (via Far Out magazine)

91. ‘31 things I've learned about becoming a better writer’ by David Perell

1. Like design, if a writer is doing their job, you never notice the writing. It's frictionless. You just keep reading.

2. The best way to differentiate yourself against AI is to write with personality. Show readers your humanity. Tell personal stories, use interesting words, and lean into the off-beat things that keep you singular.

3. The things you know the most about are the things you’ll be able to write the best about, but the challenge is that once you know a lot about something, you’ll stop seeing it. Talking to people is the best way to discover what you should write about.

4. The world doesn’t reward the people with the best ideas. It rewards the people who are best at communicating ideas.

5. Read your work out loud. You’ll be amazed at all the little places that trip you up. Then, use what you’ve learned to make your writing high-signal and smooth as butter.

6. The most interesting ideas are right in front of us. We assume that if an idea is important, it’s going to be hard to find. But sometimes, the best ideas come from the things that everybody sees, but nobody takes seriously.

7. You can almost always improve your writing by being more specific. Don’t write “I got in my car” when you can write “I got in my ‘65 Mustang.”

8. Don’t try to write about too many things at once (one of the biggest mistakes that young writers make). Instead, narrow your scope. Trade “A History of Cars” for “Saying Goodbye to Dad’s Beat-Down Mercury Station Wagon.”

9. Forget sounding smart. Be useful instead.

10. Storytelling 101: Stories are built on suspense, suspense is built on high stakes, high stakes are built on a character having a strong desire and an obstacle in the way of them getting what they want.

11. If you want to improve your voice, read outside your sphere of expertise.

12. Writer’s block is the tyranny of expectations. Block happens when your attention is on what other people think of your ideas rather than the ideas themselves. There’s a time and place for caring what others think, but it’s definitely not your first draft.

13. Read whenever you have a moment to spare — eating breakfast, waiting in line at the grocery store, and right after climbing into bed. Even though you'll forget the vast majority of what you consume, reading will change you profoundly and influence your writing style in strange and mysterious ways.

14. The fastest way to improve your stories is to cut the backstory. Jump into the heat of the action.

15. Once you embrace the fact that your first draft will be junk, writing gets way easier. And more fun…

16. Writing is hard, which means you’ll try to avoid it. To be productive, you have to treat yourself like a child. Disable your texts, turn off the Internet, and ban yourself from email. This reduction in freedom will lead to an increase in productivity.

17. Ironically, imitation fosters originality. When you imitate someone’s style, you find your own (The Beatles started as a cover band.)

18. Memorizing poetry makes you a better writer. Memorization takes place in the body just as much as the mind, and the words you memorize will become a part of you. There’s a reason we talk about “knowing things by heart.”

19. Great writing is the art of compression. All creative work is.

20. The simplest way to improve the rhythm of your writing is to vary the length of your sentences (and the words inside of them).

21. Removing excess words is good advice, but it ends up driving people to cut all the life from their writing until it becomes overly minimalistic. Don’t suck the life out of your writing in the name of grammar.

22. The entire point of knowing the rules is so you know exactly when to break them.

23. Many of your friends will be afraid to give you harsh feedback. Remedy that by asking: “What’s the 10% I need to keep, no matter what? A followup question: “What’s the 10% I’ll cut, if I absolutely had to cut?” (Got this from my interview with Tim Ferriss).

24. The process of rewriting won't just improve your original ideas. It'll generate new ideas too (most of these maxims are things I hadn’t thought about before I started working on them).

25. Concrete writing resonates. Abstract writing puts people to sleep. Bring your words to life by making them vivid and tangible. Use specific examples. Talk about things people can see, touch, taste, smell, and hear.

26, If you struggle to write, try speaking out your first drafts, then revising the typed copy. This is exactly how Churchill wrote his speeches. The only difference is that he spoke to a secretary. You can speak to a computer which will automatically transcribe what you say.

27. Whenever you can center a story around people, do it. People Magazine is the world’s most popular magazine for a reason: people want to hear about people. 28. You don’t have writer’s block. You’re just scared to say what you actually think. As my friend Jeremy Giffon says: “The best writing prompt for when I'm stuck is simply ‘be more honest.”

29. When writing non-fiction, bury yourself in a well-written fiction book. The contrast in style and content will keep you focused on your own work, but the beauty will seep into your writing.

30. You see the world through whatever topic you’re writing about. Once you start writing, you’ll start seeing the idea everywhere, like when you get a new car and suddenly spot it all over town.

31. Lists like this won’t help much if your fingers aren’t hitting the keyboard. So if you’re serious about the craft, stop reading posts like this and start writing.

92. Paul Graham on writing, briefly

93. Sam Altman on the magnetism of blogging

94. Latin proverbs (h/t @latinedisce)

Esse quam vidērī — “To be, rather than to seem.”

Aut viam inveniam aut faciam — “I shall either find a way or make one.”

Ōderint, dum metuant — “Let them hate, as long as they fear.”

Festīnā lentē — “Make haste slowly.”

Audentēs fortūna iuvat — “Fortune favours the brave.”

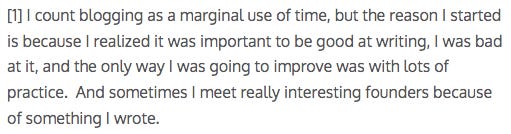

95. Three ideas on writing, by David Perell

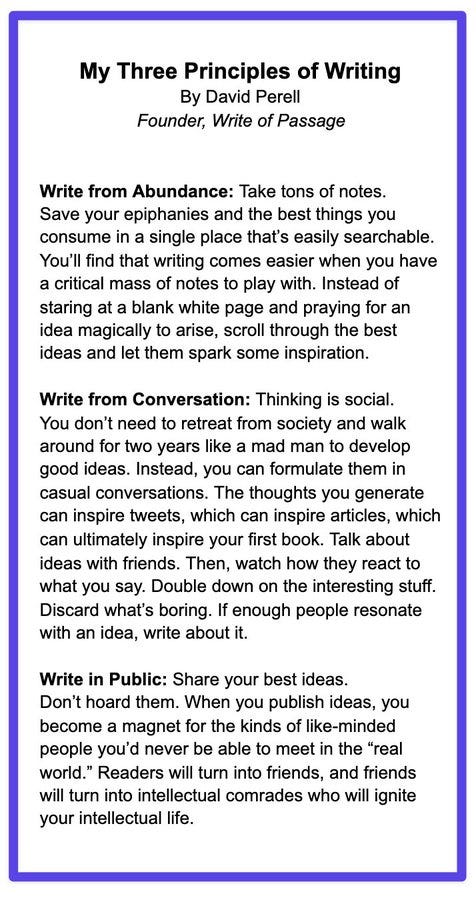

96. Howard Marks on writing for yourself (h/t Morgan Housel)

97. Chuck Palahniuk on ‘looking again’ (h/t Tim Ferriss)

Tim Ferriss: This is going to be a lazy question, but I’ll ask it anyway, because I’m so curious having never had anything made into a movie. How would you summarize what your experience was like, going from pre-movie to say, a few years after the movie came out? How would you summarize or describe that experience? I just, I really can’t even imagine emotionally what it looked like or felt like.

Chuck Palahniuk: I could only talk about it. I always try to be as specific as possible and address maybe just one aspect of something rather than try to sort of generalize about the entire thing. And one interesting aspect that I’ve grown to appreciate is that when you do a thousand press junkets for a movie, and you’re asked the same questions over and over, it’s kind of like, the whole Buddhist concept of “Look again.” Look again, look again. And you are — it’s as if you’re being psychoanalyzed by a million strangers who have no emotional attachment to your action, to your answer. But you are still looking a little deeper and trying to reinvent the thing every time you look at it.

And so often it takes that kind of really thorough coaching before you realize what you actually wrote about, and suddenly, you can realize in the middle of some roomful of reporters, the thing, the dark, secret, horrible thing that you were actually writing about, and you can be mortified. You put this thing on the page, and then you spend the whole rest of that meeting with a smile just pinned on your face, praying that no one will ever realize what you were actually writing about. And it’s painful, but I would rather it happens eventually than never happened. Because it’s extraordinary to see how your subconscious was working that whole time.

And in a way, as you’re writing, you are trying to trick yourself to go to a place that you would never consciously go to. And at the same time, you’re trying to trick the reader to go to a place that they would never consciously go to. And to have a reaction to something that they do not want to fully recognize. And that’s kind of the glory of minimalism.

Tim Ferriss: I don’t expect an answer here. So feel free not to answer if you prefer, but what did you discover? What were you actually writing about?

Chuck Palahniuk: Oh, hell no, I’m not going to go there. No, number one, because it’s always so fantastically dark, and personal, and suppressed. Number two, I’m afraid if I ever get that specific with my intention, it will preclude the readers’ sort of interpretation. And it won’t have any power for the reader because suddenly there’ll be this correct interpretation. And if the reader doesn’t conform to that, then the reader is wrong. And again, it’s never about making the reader wrong. It’s about making the reader right and giving them a rush of being right over and over.

Tim Ferriss: Couldn’t have asked for a better answer. Thank you for that. Do you ever worry after writing something or at any point that you will write something and at some point be sitting in a meeting and you have this flash of insight about what you are actually writing about that is so dark because it plunges you headlong into some type of abyss that is difficult to climb out of?

Chuck Palahniuk: No, it’s never really as if it’s plunged into an abyss, because any kind of revelation like that is such a relief. It’s gaining access, being able to retrieve something that had been so completely lost to me that I feel a fantastic joy when even those darkest things come to the surface.

Yeah, because at least I know what I’m dealing with, and I’m no longer used by it. I’m using it. And that’s my advice to writers. The dangerous writing is that so many of these are used by aspects of our history, our past, our experience, without fully understanding them. And once we can unpack them in the seemingly innocuous world of fiction, then we can more fully look at them, and be aware of them and not be used by them.

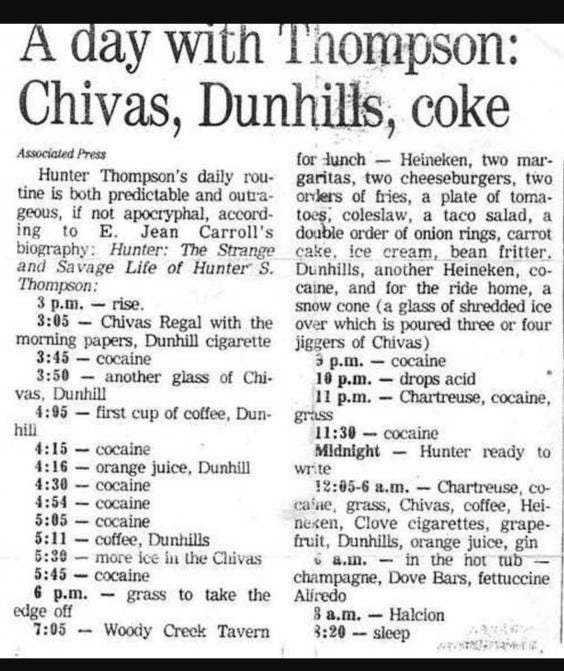

98. Hunter S. Thompson on routine

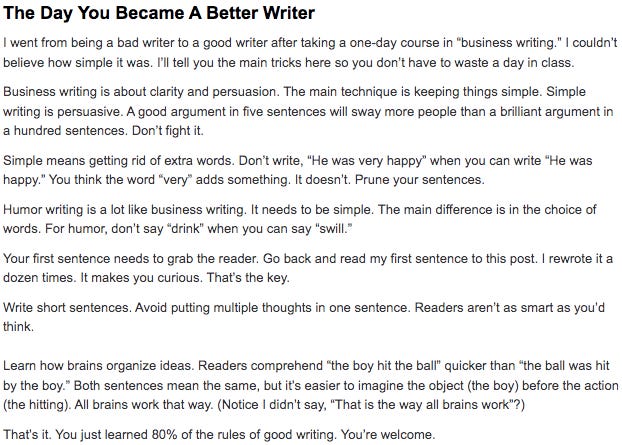

99. Scott Adams on The Day You Became A Better Writer

100. Lessons from Shaan Puri on the How I Write podcast

A formula for a great story: Intention + Obstacle. At all moments, the listener should know what the hero wants and what's stopping them from getting there. This one's from Aaron Sorkin, who wrote The Social Network.

Work backwards from the emotion you're trying to create in the reader - joy, surprise, amusement, outrage - then let the structure follow.

Aim for strong reactions. If you can get the reader to widen their eyes, raise their eyebrows, and/or burst out laughing, they will share your work.

Don't write to the faceless masses. Write to one specific person. BuzzFeed writers used to write to "Debbie at her Desk," the mythical bored woman at her desk who wanted a 5-minute distraction ("The most powerful network in the world is the bored at work network.")

“Likeability” is downstream of vulnerability. The more honestly you share your challenges, the more invested your reader gets. Write your heart out.

Forget resumes and portfolios. Create a “binge bank” instead. A binge bank is a set of videos or essays that people can binge on. Stack up material so that when people do go down your rabbit hole, they come out the other side a fan.

Your writing should only be as long as it is interesting. An uninteresting 20 second reel will fail; an interesting 30-minute essay will win. But you must be honest while gauging how objectively interesting your piece is…in a world with infinite content.

Thanks for the compilation! What a gift ! Many thanks

…amazing list of inspiration…bravo on getting it all together…