The Meesho Must Go On

A Spotlight on...Whatsapp Boutiques, four-way flywheels, 'Listen Or Die', and the marketplace that solved Middle India

Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 210 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece, about amphibious airplanes and ashtrays made by Saldavor Dali.

This week we’re taking off from startup-land and diving into India’s public markets. Strap in below👇

This edition of Tigerfeathers is presented by…Runtime

“Fast, sharp, builder-first updates from India’s tech frontline.”

Broadcast daily from Indiranagar - the nerve centre of Indian tech - Runtime is a bite-sized daily supplement that should be in every builder’s information diet.

Hosted by Caleb Friesen (the creator of popular YouTube channel ‘Backstage with Millionaires’), Runtime covers the most important updates in Indian tech from the past 24 hours. Its daily news videos are three minutes long and you can watch them basically everywhere: YouTube, Instagram, X and LinkedIn.

The channel also conducts livestreams, office tours and site visits to bring you real-time insights from the movers, shakers and builders in India’s tech ecosystem.

Tune into Runtime via your channel of choice. Start with the YouTube page here:

And if you’re interested in partnering with us on a future edition of Tigerfeathers, hit us up on Twitter/LinkedIn or by replying to this email. With that, let’s get to it.

You would have to be cut from a very specific kind of cloth to mistake Man’s Search For Meaning for a startup guide.

Viktor Frankl’s harrowing memoir about the psychology of survival and the search for purpose in unimaginable circumstances wouldn’t normally share the same shelf as Zero To One. There are no secrets of Product-Market-Fit buried between accounts of existential despair and triumphant tales of the human spirit preavailing over profound injustice.

Frankl’s classic does, however, offer a handful of enduring truths on how to anchor yourself when the ground beneath you disappears, many of which the author distils into a single sentence that remains one of the book’s signature axioms:

“Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’.”

Now, we’ll concede that this is an odd place to begin a piece about an Indian e-commerce startup gearing up for its IPO. But if you spend time studying the ten-year journey of Meesho, and listening to a decade’s worth of interviews with its founders - Vidit Aatrey and Sanjeev Barnwal - the quote above starts to feel less philosophical and more operational, as the most conspicuous facet of their story crystalises into focus.

Meesho is a company that had its ‘why’ from Day 1.

This ‘why’ has stayed constant throughout its journey, even as the ‘how’ has shapeshifted from pivot to pivot and product to product, all in service of the same mission - to spread the gospel of e-commerce beyond India’s metro cities; to bring the mass market of buyers and sellers in India online for the first time; to make online shopping legible and accessible to ‘Middle India’ (i.e. Bharat).

As the company gears up to raise ₹5,421 crore (~$600 million) next week in an IPO that could value it at ₹50,096 crore (~USD 5.6 billion), it would appear that that mission is in good health.

For reasons that we’ll go over below, Meesho’s public listing is a genuine milestone in the 21st century saga of Indian tech, and it’s one we thought merited proper unpacking. To do this unpacking, we are fortunate to once again call upon the wit and wisdom of Paavan Gami, who returns for his second Tigerfeathers Spotlight edition, and his second IPO breakdown of the year, after masterfully dissecting the prospectus of Urban Company (another Indian consumer-tech stalwart) back in July. If you’re new here, or you missed Paavan’s guest post the first time around, here’s a refresher on who you’re going to be hearing from today.

Into The Spotlight (Again)

Paavan is the founder and managing partner of Raas Partners, a US-based investment firm predicated on taking a concentrated, long-term approach to investing in Indian public equities.

Before starting Raas, he cut his teeth at McKinsey, SPO Partners, and the storied Greenoaks Capital, where he worked alongside investing wunderkind Neil Mehta in search of companies that offer JDCEs (“Jaw-Dropping Customer Experiences”, not Jealous Dragons Collecting Emeralds, in case you were wondering).

Raas isn’t looking for hot stock tips or to ride seasonal or sectoral rotations. Instead they’re obsessed with what Paavan calls “Inevitables” — businesses with such strong competitive moats and exceptional founders that their long-term dominance feels, well, inevitable. Think of it as venture capital thinking applied to public markets: at the simplest level, they’re betting on founder-led companies that are still early enough in their journeys and have “strongform rights to win” in massive, fragmented Indian markets. Their intention is to hold a handful of these ‘Inevitable’ companies for years rather than owning dozens of good-not-great candidates, aiming to build “a firm with venture-like compounding advantages”.

He borrows the terminology from Warren Buffett’s 1997 shareholder letter, where Buffett writes that: “Companies such as Coca-Cola and Gillette might well be labeled “The Inevitables”… no sensible observer - not even these companies’ most vigorous competitors - questions that Coke and Gillette will dominate their fields worldwide for an investment lifetime. Indeed, their dominance will probably strengthen … Charlie and I can identify only a few Inevitables, even after a lifetime of looking for them.”

When it comes to searching for Inevitables in India, Paavan’s thesis is that the country’s supply-side constraints create longer periods of supernormal profits than you’d see elsewhere. Poor infrastructure, red tape, and capital scarcity mean that when a great business gets established, competitors are slower to emerge, thereby giving incumbents an extended runway to compound their advantages. It’s why India’s public markets exhibit such a potent Power Law when it comes to sectoral leadership. From his POV, India has the opposite of China’s hyper-competitive dynamics, where fast followers can quickly erode early leads.

What buttresses Raas Partners’ work is the observation that in India most high-growth companies go public much earlier than they would in the US, meaning you can theoretically invest in tomorrow’s category winners at today’s prices if you know what you’re looking for. Added to this is Paavan’s belief that the country’s economy is still relatively nascent and unorganised, meaning there is plenty of runway to grow at the macro and micro level, making India “one of the world’s best hunting grounds for exceptional long-term public market investments”. Eschewing the typical quarterly financial beats, Raas aims to build conviction on where their potential ‘portfolio companies’ will be in 2030.

Earlier this year we had the chance to read some of Paavan’s company research reports. The insane level of depth and thoughtfulness and originality was immediately apparent.

When it comes to public company analysis, Paavan is a Special One, and we were keen to offer him a stage to do his thing for the Tigerfeathers crowd. His first piece on Urban Company’s (then) upcoming IPO was as on-brand as it gets, and it resonated well beyond our usual audience. People who knew the company inside-out told us it was the single most comprehensive piece of analysis they’d encountered in the lead up to its listing. Even folks intimately familiar with the story and the numbers reached out to say they’d learned something new.

Unsurprisngly, we’ve been pestering Paavan to follow up on his debut for a few months now, collectively waiting for the right time and the right company…which brings us to this week.

Welcome to the Meesho

2025 has seen a parade of Indian startups hit the public bourses. There’s been no shortage of great companies with great stories and great founders to cover as they enter their next phase as listed companies. So why have we decided to focus our attention (and yours) on Meesho?

Because, much like the vada pav, the Kingfisher pint, the Unified Payments Interface, and the word ‘prepone’, Meesho is a uniquely Indian creation. It presents perhaps the most vivid portrait of contradiction and narrative violation that you will find in India, made clearer by the fact that its books are now open to closer examination.

For the uninitiated, Meesho is an e-commerce marketplace that connects small businesses and individual sellers with Indian shoppers…

…and therein lies the first contradiction. You should be initiated with Meesho.

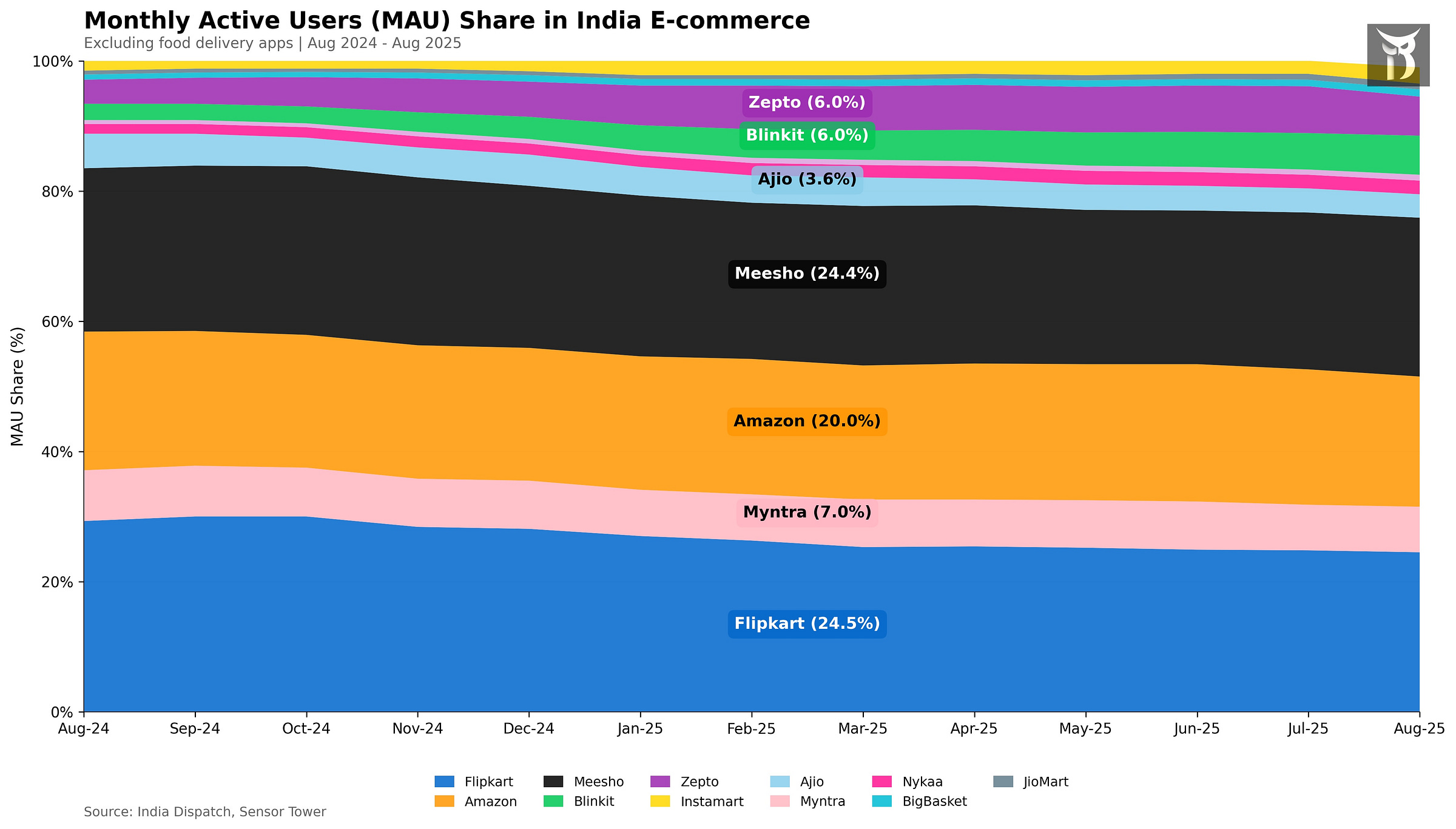

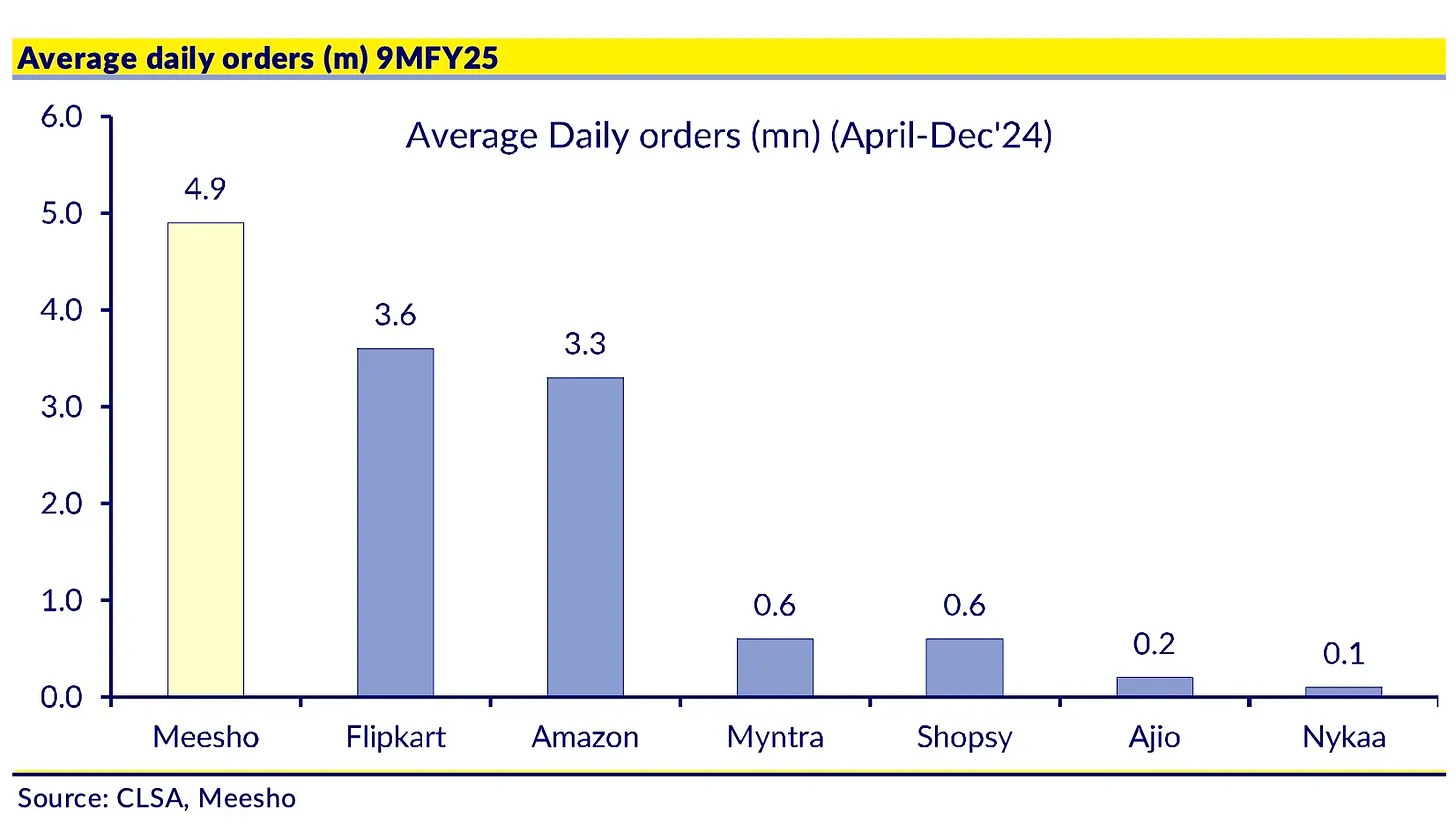

Meesho is not just an Indian e-commerce marketplace, it is the leading e-commerce platform in the country by order volume, making it larger than even Amazon, Flipkart, or anyone else.

The funny thing is that if you happen to live in one of India’s Tier 1 cities; if English is your first language; if most of your purchases are branded items; and if you’re happy paying a higher price for the convenience of 10-minute delivery or (gasp) next-day delivery; then there’s a good chance you haven’t even heard of Meesho, much less ordered something on it (we hadn’t ordered anything on Meesho till we started working on this thing, so don’t feel too bad).

None of this is accidental. Meesho isn’t concerned about serving the needs of large enterprises or affluent metro-dwelling Indian consumers. Meesho exists to serve the needs of the kinds of buyers and sellers that ‘traditional’ e-commerce platforms in India had long ignored.

It was first conceived in 2015 by former IIT Delhi batchmates Vidit Aatrey and Sanjeev Barnwal as a hyperlocal fashion discovery app called Fashnear. It then pivoted to becoming a Shopify-like storefront generator for offline sellers, before transforming into a reseller-driven social commerce platform where millions of micro-entrepreneurs—primarily housewives and small sellers—curated and sold products through WhatsApp and Facebook. In 2021, it pivoted once more into its current avatar: a horizontal consumer-facing shopping app.

If you’re someone who resides in this Meesho-metro-blind-spot, then what you’ve missed is one of the boldest and most imaginative e-commerce experiments playing out anywhere in the world. Given that Meesho began its journey by targeting buyers and sellers who had never transacted online before, it had to develop an entirely different set of muscles than Amazon or Flipkart or Nykaa or Ajio.

The incumbents could assume their customers understood how e-commerce worked; Meesho couldn’t. So it built a zero-commission marketplace to entice wary sellers to come online. It made discovery, not search, the primary shopping mechanic—because its customers were used to browsing physical bazaars without preconceived buying intent. It turned influencers into its growth engine instead of performance marketing, using content creators as a proxy to build trust with shoppers who were used to buying local. It shipped products in a week when rivals obsessed over same-day delivery (and now 10-minute delivery). And critically, it stayed asset-light—no warehouses, no inventory, no trucks—even as it built its own logistics network (Valmo) to reach the pincodes the giants ignored.

That cocktail of counterintuitive bets—each one going against the grain of how e-commerce “should” work, has resulted in a company that now moves more orders than Amazon or Flipkart, operates with positive cash flow, and is approaching profitability - all while serving mostly unbranded goods at an average order value of just ₹274 to price-conscious consumers largely based in Tier 2, Tier 3, and Tier 4 cities in India, without needing to charge its sellers a commission.

As India’s first horizontal e-commerce platform to go public, Meesho is a case study in how serving the underserved requires building from first principles. Much like Urban Company, it’s an enterprise that has gone the distance by aligning its interests and incentives with that of its community, betting its success on an almost maniacal commitment to listening to its users.

The big question at hand now, is whether that alignment can sustain itself in India’s public markets.

What you’ll get from reading this

Before we kick things off, it’s worth setting expectations here about what this piece is and what it isn’t.

This is not a chapter-by-chapter story of Meesho, nor is it a biography of its co-founders. If you’re interested in that kind of thing we recommend listening to any of Vidit and Sanjeev’s podcast appearances over the years (this one with Peak XV’s Mohit Bhatnagar and this one with CNBC-TV18’s Sonia Shenoy are a good start). We’ve also added a bunch of links to relevant articles, podcasts and interviews in the bibliography at the end of the piece for those keen to dive deeper.

What this piece is, is a dissection of Meesho’s numbers, performance, strategy and future prospects from the perspective of someone whose day job it is to take a dispassionate and long term lens to public markets in India, specifically in search of companies that fit within his fund’s ‘Inevitability’ framework. (There’s a good chance that, by the end of this piece, you will know Meesho better than you know members of your own family).

Paavan’s analysis mostly draws from the information disclosed in Meesho’s red herring prospectus (RHP), its annual report for 2023-24, the official investor report published by Redseer, and several primary interviews with inhabitants from India’s startup ecosystem. Needless to say, nothing in the paragraphs below should be construed as financial advice. If you’re looking for get rich quick tips, we’ve got six Nigerian princes on retainer who’d be happy to share their favourite tactics to building GENERATIONAL WEALTH TODAY🤑🤑🤑 in exchange for a small upfront fee (no but seriously, none of this is financial advice, pls do your own research).

With that said, we will take our leave and cede the floor to Paavan. Aside from the odd meme, comment or bit of formatting, the words you’ll read are his. We hope you enjoy learning from him as much as we did. Let’s get to it.

Right, let’s set the scene.

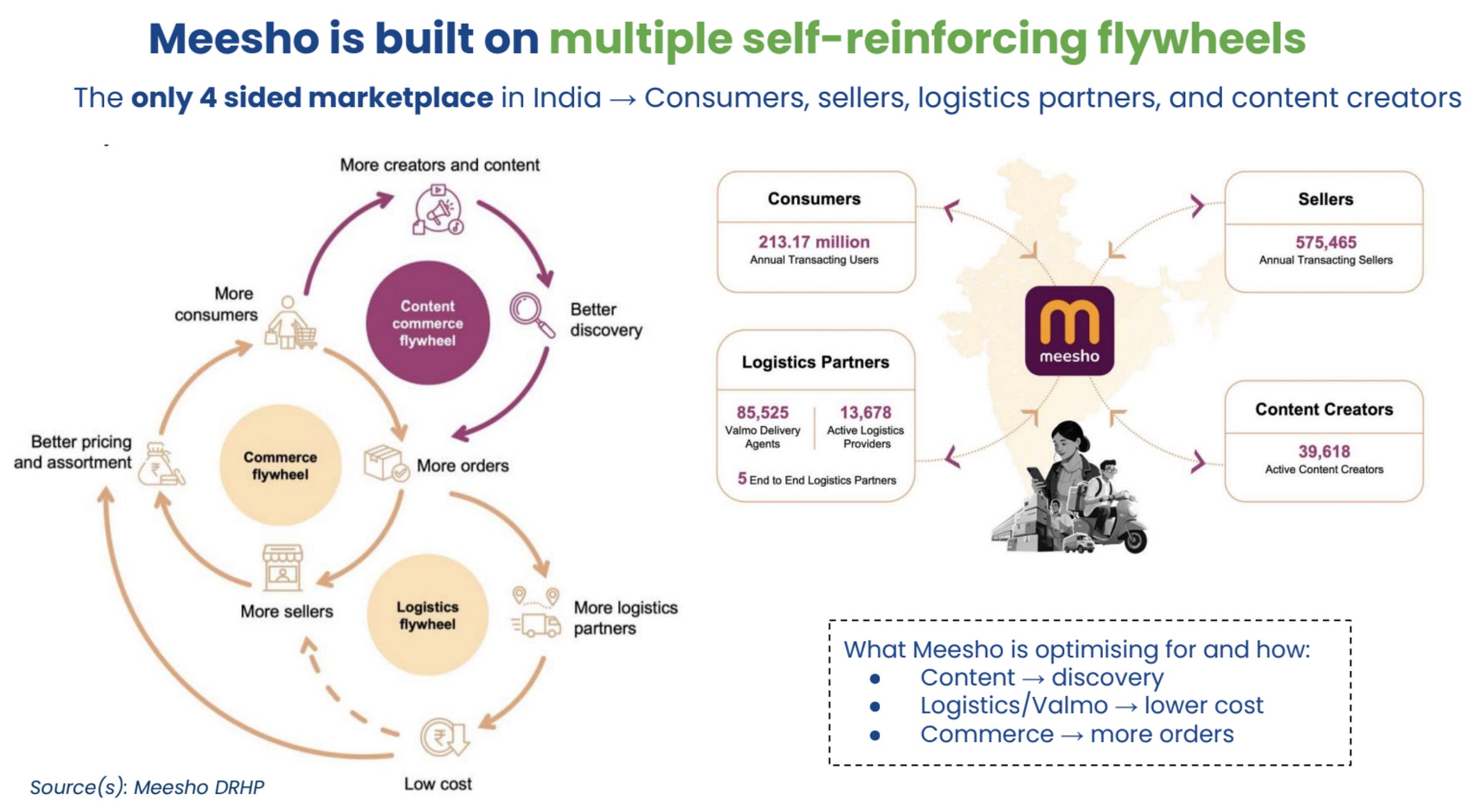

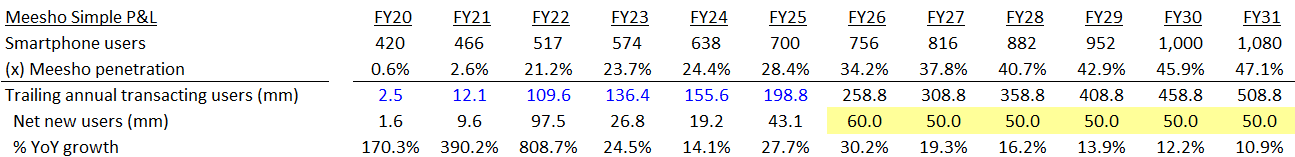

Despite being a few years younger than its big brothers (Flipkart and Amazon India), Meesho is now the largest e-commerce platform in India by transacting users, orders, and, in our view, underlying earnings power. One in five Indian adults (and likely more, given that some households share accounts) shop at Meesho nearly ten times per year, putting it in the league of very few truly ‘population scale’ platforms in India.

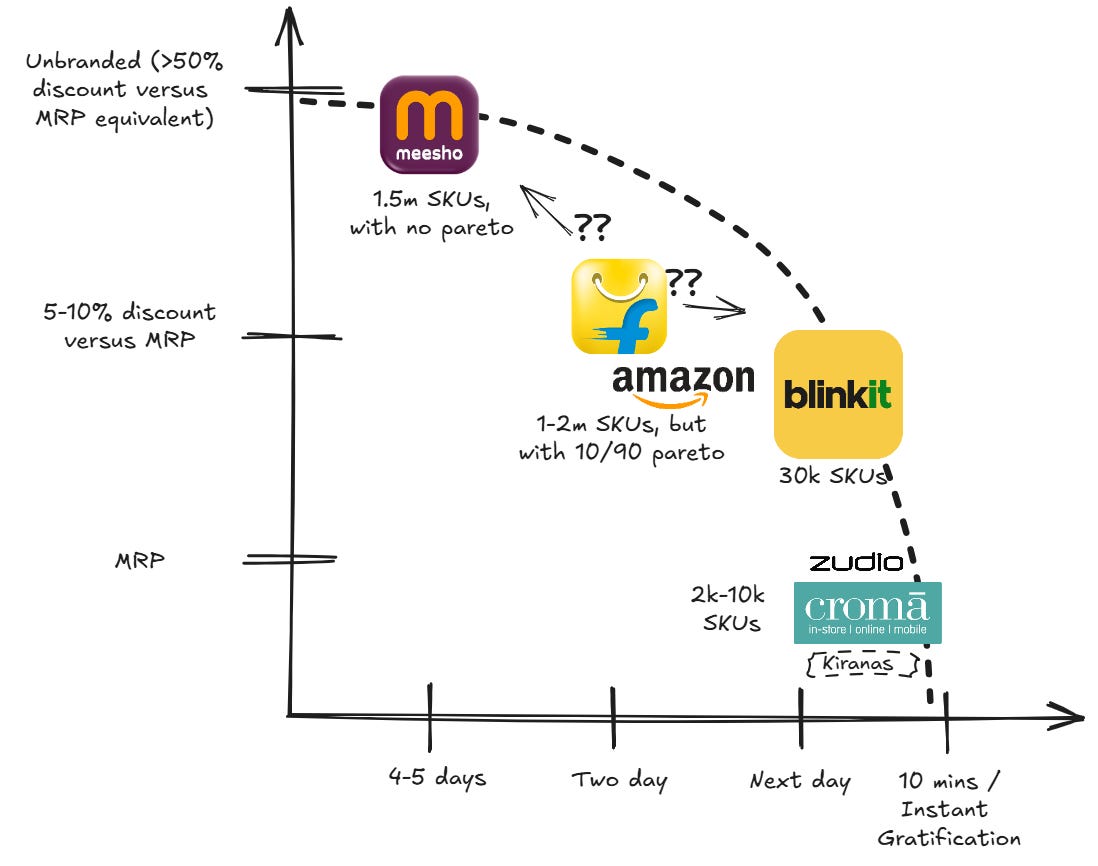

Meesho is part of a two-sided attack on India’s e-commerce ‘OGs’, Flipkart and Amazon India…On one end, their core India 1 audience is rapidly adopting quick commerce, initially for groceries but increasingly also for general merchandise (>25% of Swiggy Instamart’s GMV is now from non-grocery items). On the other end, the India 2 & 3 customer base in smaller towns, who were left out of the first wave of Indian ecommerce, has adopted Meesho as their platform of choice. Meesho differentiates on everyday (low) ‘price’ and (high) ‘selection’, especially on long-tail unbranded categories like fashion, beauty, and home goods, while Blinkit, Instamart, Zepto et al differentiate via unbelievable ‘convenience’.

This has left Flipkart and Amazon trapped in an unenviable no man’s land - forced to fight on two fronts they never prepared for.

They need to rapidly develop competing offerings on both the ‘value’ and ‘convenience’ vectors to stay relevant. This type of innovator’s dilemma is compounded by slow decision making, given that neither Flipkart nor Amazon India are founder-run businesses at this point (they are instead composed of many fiefdoms) and given that neither are entirely in control of their own purse strings (being somewhat beholden to their US based parent entities - Walmart and Amazon respectively). As they’ve gone head to head for premiership in the top table of India’s e-commerce arena, Meesho has quietly come up from behind and carved a large chunk of pie for itself. If current trajectories hold, Meesho could lap them both and end up building the larger business over time.

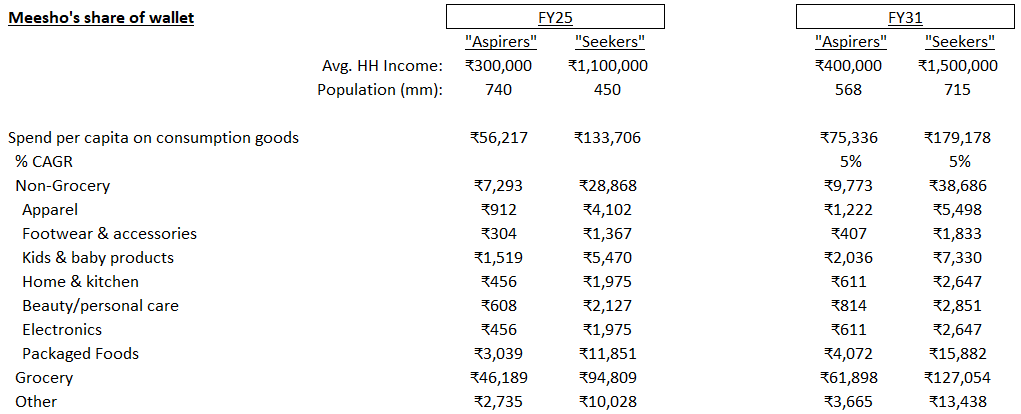

Meesho’s success is not an aberration but instead represents a broader pattern of digital dollar-stores winning significant market share globally as the mass market segment has come online and ecommerce has moved beyond its initial convenience-first value proposition. Meesho’s analogs in China and Indonesia – PDD (which operates Pinduoduo and Temu) and Shopee – are worth $160bn and $80bn respectively. Partly the valuations they garner are driven by their highly profitable core marketplace businesses and partly because they’ve launched a number of other successful products (across grocery, payments, and lending) to further serve the users they’ve aggregated.

Meesho could follow a similar trajectory over time as the first transactional internet platform to aggregate a Bharat user base. As India’s GDP per capita converges with those economies over the next 10-20 years, could Meesho march towards being worth $100+bn over time?

Given that potential, we are witnessing the IPO of what is likely to be one of India’s most important companies. The analysis below will briefly touch on Meesho’s origin story, before turning focus to the drivers of their core marketplace flywheel, the reasons for why that flywheel could accelerate further, their long-term profitability potential, and so on.

Cool, where do we start?

Let’s start in 2015.

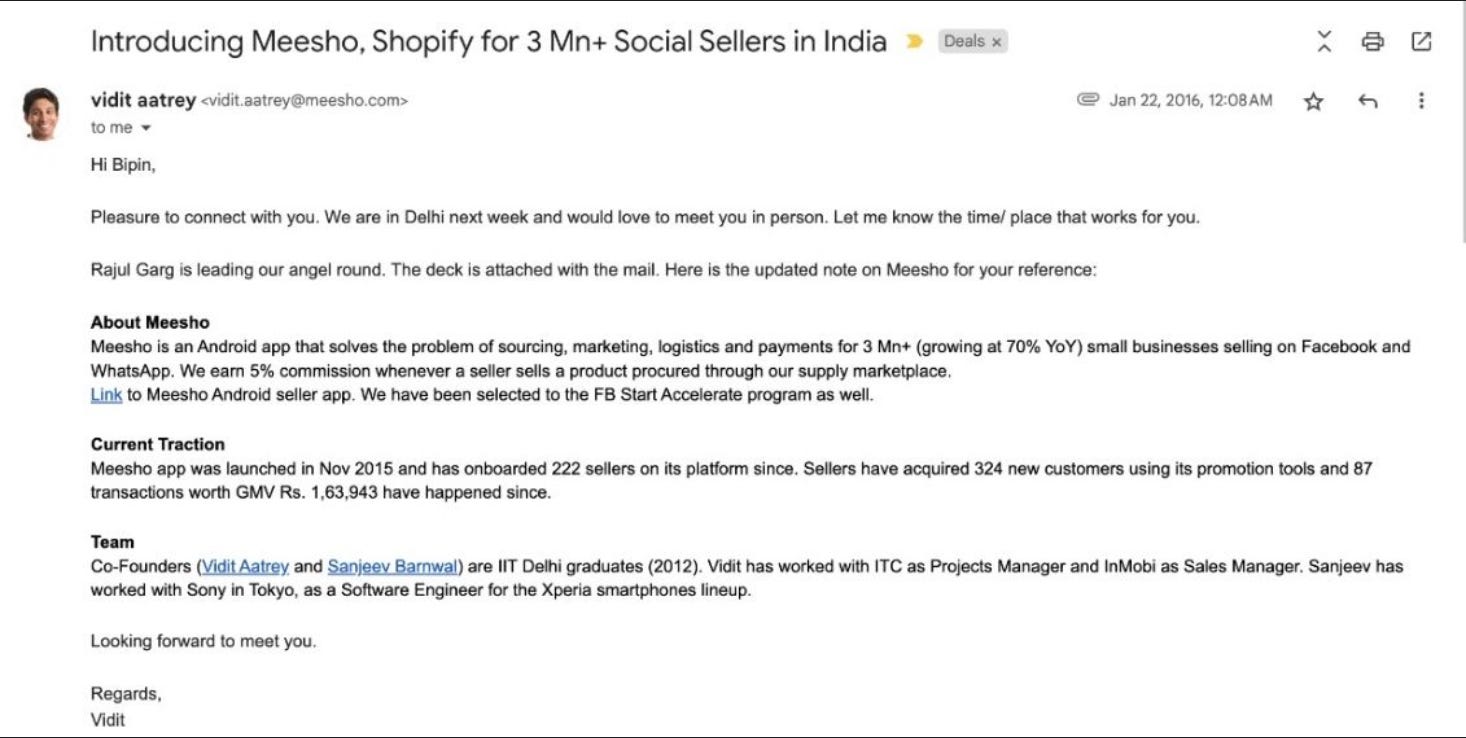

Vidit Aatrey and Sanjeev Barnwal were batchmates who became friends at IIT Delhi. After graduating in 2012, they went their separate ways: Vidit worked at ITC in Chennai and then InMobi in Bangalore, while Sanjeev joined Sony’s core tech team in Japan, working on camera technology. In 2015, basically “out of the blue” Sanjeev called Vidit, who was then at InMobi, to ask for his advice as part of his diligence on another Indian startup that he was considering joining. Vidit suggested they start something together instead. They quit their jobs practically on the spot, taking the plunge into entrepreneurship.

A week later they had already begun tossing around ideas for their new venture. The duo had two criteria they installed while weighing up different options - (i) they wanted to tackle a ‘big’ problem so they could remain motivated to keep solving for it over the course of their lifetimes; and (ii) having both grown up in humble, lower middle class households, they wanted to solve the issues faced by people around them, so they could personally identify with the problem and take pride in alleviating it.

At the time, in 2015, Indian e-commerce was having its moment. Flipkart had just raised $700 million at a stunning $15 billion valuation (more than Indian Oil Corporation’s market cap at the time), Snapdeal had pulled in $500 million from Alibaba, Foxconn and SoftBank at a $6.5 billion valuation, and Amazon had committed $2 billion to crack India after launching just two years prior. The battle for India’s online shoppers was well underway, and it was natural that any ambitious young founders starting up would look to the Internet for inspiration.

Vidit and Sanjeev similarly set their sights on tackling the consumer e-commerce opportunity, but felt that large categories like electronics were already being well served by the Flipkarts of the world. To figure out where to focus, they made a spreadsheet —placing popular emerging tech business models (Airbnb/Uber/hyperlocal) in each row and viable sectors (groceries, travel, e-commerce) across each column, literally looking for gaps to exploit. They found that while there were many players doing hyperlocal and many doing fashion, there was an opening at the intersection of the two.

This idea was simultaeously fuelled by an observation. Despite the noise being generated by the Indian e-commerce story, none of the people around them seemed to be buying anything online. It was because the leading marketplace platforms were initially only looking to woo the attention of affluent urban consumers, and so had ignored the needs and aspirations of small town India, focusing on higher ticker price items and branded products. Those offerings had no relevance to customers in Tier 2 and Tier 3 India, who typically bought what they needed from local vendors, kirana stores, and small businesses run by people from their community. Because none of these entities were selling online, none of their customers were buying online either. Vidit and Sanjeev realised that the key to unlocking digital commerce beyond India’s metro cities was bringing the country’s small businesses online. This, coupled with their spreadsheet discovery of Hyperlocal X Fashion, sowed the seeds for their new venture.

The first product they launched was called “Fashnear”, which, true to the name, aggregated the apparel items available at local fashion stores and made them available in an app - like a Swiggy-for-fashion. (Fun fact - Fashnear Pvt. Ltd. was Meesho’s official corporate entity’s name until earlier this year). The duo launched Fashnear in mid-2015. The initial sellers were personally onboarded by the two of them —the entire operation at this point was just two guys with laptops— in HSR Layout and Koramangala in Bangalore.

I’m guessing this didn’t work out so well, considering Fashnear doesn’t exist today?

In Vidit’s telling, they pretty immediately recognized that this was not a good model. They were neither providing the selection of a digital ‘endless aisle’ nor the convenience of home delivery nor the ability to try on the clothes. It was the worst of both worlds. They decided to switch things up.

For the next six months, they embedded themselves in the lives of Fashnear users. They sat down with their sellers in a series of discovery sessions to identify real pain points that needed addressing, observing the the rhythms of their everyday routines. In particular, Vidit spent hours sitting inside a boutique called Estilo Canta in Koramangala, watching how the business actually operated.

He noticed something curious: at checkout, the shopkeeper—a Malayali man who’d been running the store for years—would ask customers for their WhatsApp number. He’d add them to a WhatsApp group where he’d regularly send photos of new inventory as it came in. When Vidit asked about it, the shopkeeper told him he was doing over 40% of his business through WhatsApp. His brother, running a similar shop in Whitefield, was doing 50-60% of his business the same way. Customers would see something they liked in the group, message back, and a delivery boy would bring it to their home. Cash on delivery. The entire transaction happened without anyone entering the store.

As they dug deeper, they realized this wasn’t unique to Estilo Canta. Shopkeepers across Bangalore—and eventually across India—were discovering the same workaround. WhatsApp had become an informal sales channel, and these small businesses were making it work despite the clunkiness of the experience.

By Dec 2015, they decided to build a product resembling a ‘mobile-first Shopify for offline merchants’ to help digitize this experience; this involved a digital storefront/catalog, a simple CRM on top of WhatsApp, and a payments capability. This iteration of the product is where the name “Meesho” (originally “Meri Shop”) comes from.

This business had much clearer product-market fit and could be scaled through digital marketing to SMEs. The natural advantage this product had was that Whatsapp was seen as an ‘essential’ app for anyone in India with a smartphone (similar to how it’s seen even today), which meant they could bootstrap their own product on top of Whatsapp’s existing network effects.

The company raised some initial seed capital (including participating in the Y Combinator summer 2016 batch) at this point and began building out the team. Once again though, after a promising start, they found retention in the app waning. The learning this time was that the Shopify product just wasn’t compelling enough to old-school (and often low margin) small businesses. Their product was aimed at solving ‘convenience’, rather than helping these businesses generate more returns - a weak (and often doomed) proposition that has led to the demise of many ‘dukaan tech’ startups attempting to build for this market.

However, they finally caught their first break, discovering some green shoots in their operation courtesy of the response from a slice of users they hadn’t even realised they were serving.

??? Spit it out man.

By late 2016, they’d noticed something unexpected: there was a subset of their user base that was far more engaged in the product than the shopkeepers they’d originally built for—women running boutique-style businesses (i.e. ‘Whatsapp Boutiques’) from their homes. These weren’t traditional retailers. They were homemakers in Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan, often in Tier 2 and 3 cities. Friends and family bought apparel from these women because they knew them personally and trusted their taste.

These businesses were entirely run on top of WhatsApp distribution (basically the women would create Whatsapp groups composed of their friends, relatives, social circle etc and curate catalogues from other sellers and vendors for this audience). In many cases these were women who had harboured dreams of being entrepreneurs and business owners, but had to shelve their ambitions due to time constraints and social pressures after getting married, or a lack of access to capital. ‘Reselling’ was an asset-light and capital-free way of running their own businesses, as they didn’t have to buy any inventory themselves - they were simply acting as a decentralised, autonomous sales force. So when this cohort found Meri Shop, they used it more seriously than the original shopkeeper persona.

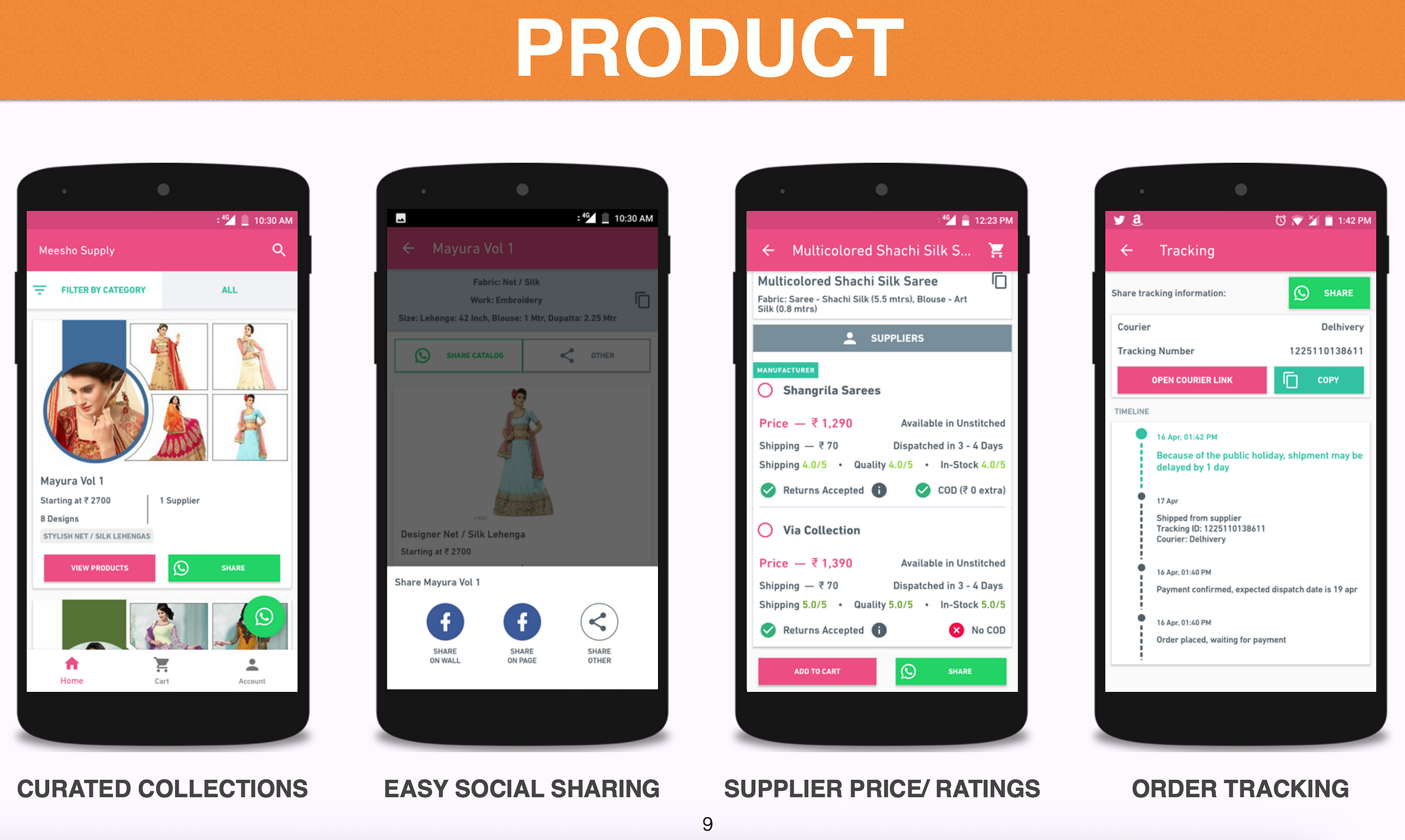

Vidit and Sanjeev decided to focus on the needs of this user base. They learned that these women had difficulties sourcing inventory; they relied on informal wholesaler networks (hence “reseller”) that offered limited selection and high prices. To address this need, they built a second product (called “Meesho Supply” initially) that was a marketplace connecting apparel wholesalers to these WhatsApp resellers.

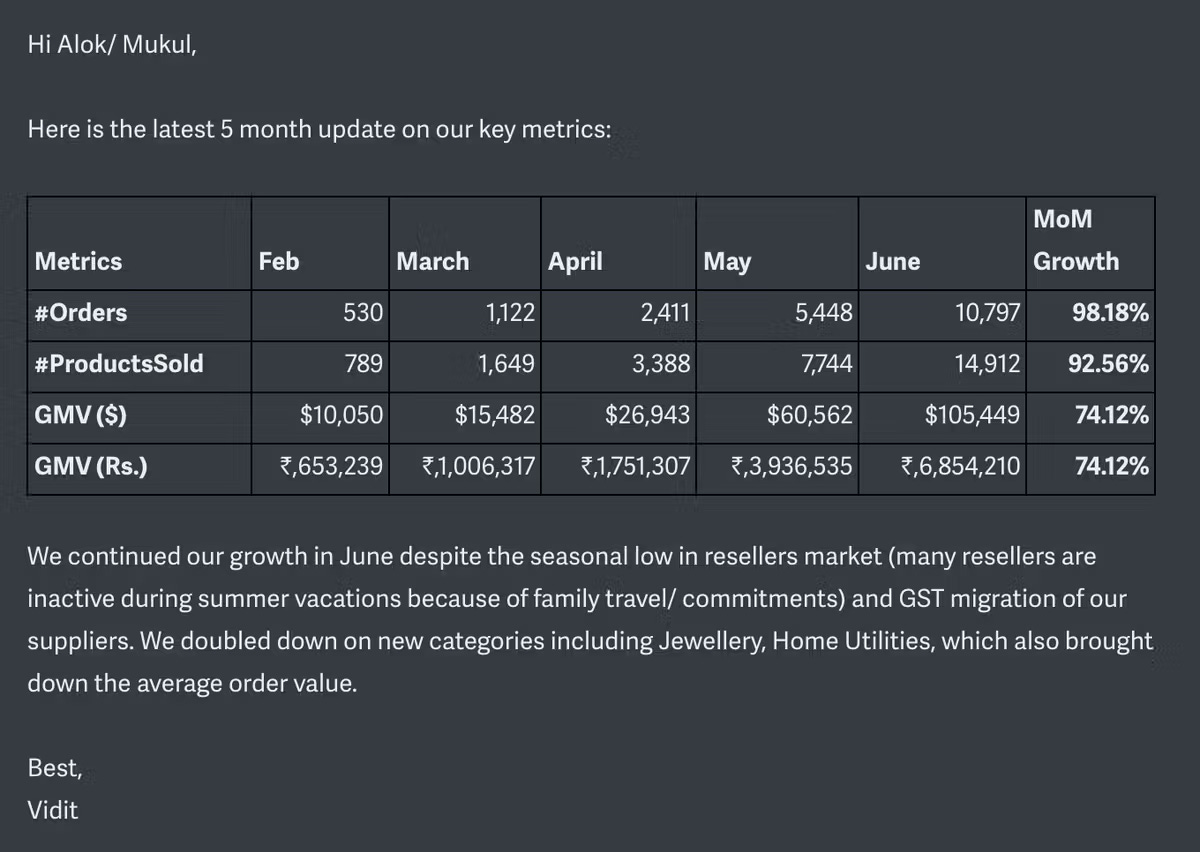

Meesho Supply caught fire quickly. Within a few months, it was doubling in size month over month, and Vidit and Sanjeev realized they couldn’t run both products in parallel. They needed to go all-in on one direction. They chose to focus solely on scaling the reseller marketplace. In summer 2017, on the basis of this growth, the newly christened Meesho raised a $2.4m Series A led by Elevation. At that time, the business was selling to ~4,000 resellers and doing ~1.5 lakh annualized orders.

Meesho’s next evolution was to actually create resellers versus onboarding existing ones (the latter was ultimately a finite pool). They did this through digital marketing, communicating that local entrepreneurs could start their own online boutiques powered by Meesho. The winning tagline was ‘Start your business online for free with zero investment’.

This “B2B2C” model grew enormously quickly. By August 2018, Meesho was powering 150,000+ resellers. By mid-2019, this had risen to 1.2m+ resellers; by mid-2020, 5m+.

Along the way, they rapidly raised more capital: a $11.5m Series B led by Sequoia India/Peak XV in mid-2018, a $50m Series C from Shunwei and RPS Ventures in late 2018, and ultimately a $125m Series D led by Facebook/Meta and Naspers in mid-2019. The latter was Facebook’s first ever investment in India, and it made strategic sense — Meesho had become one of the largest apps built on top of WhatsApp globally by this time.

Why did this B2B2C model work so well though?

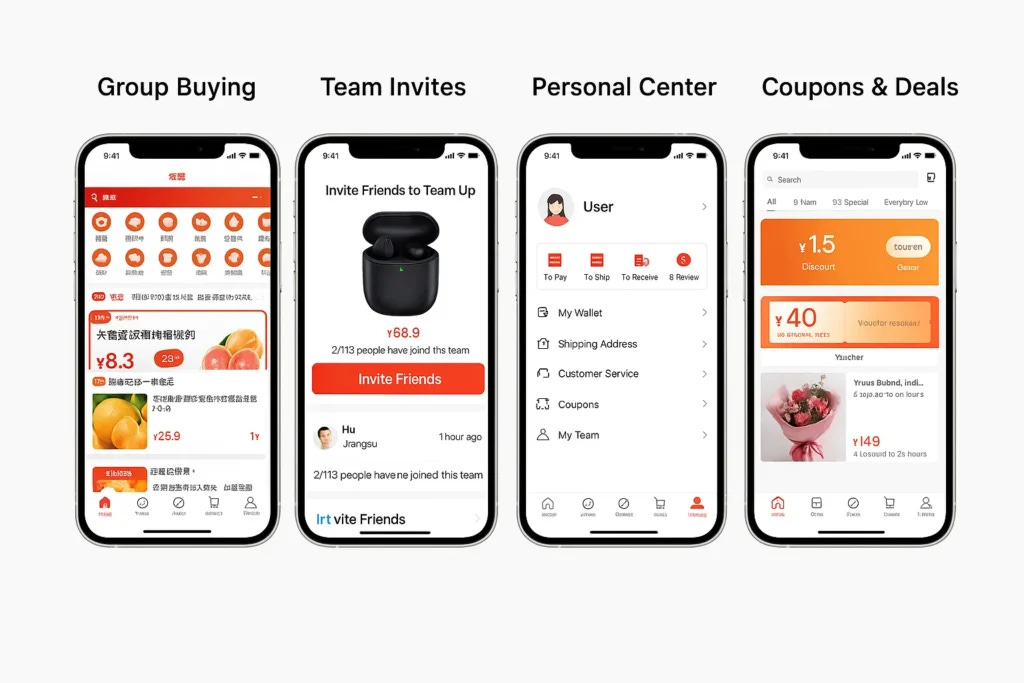

Well, by 2017-2018, Meesho’s reseller business model had converged with a wave of contemporaneous “social commerce” companies like PDD (founded in 2015), Xingsheng (founded in 2018), Shihuituan (founded in 2018), and Shopee (founded in 2015).

Meesho ended up being the masthead for this category in India, though importantly they arrived there in a much more organic way than others who had launched “X for Y” social commerce copycats.

Conceptually, Meesho’s reseller model solved two important problems that had previously hindered ecommerce adoption among rural users (and these problems were relevant across geographies, not just in India): (i) trust and onboarding friction; (ii) order economics:

Trust and onboarding friction – Meesho’s customers had just gotten online via Jio two years prior, and so their ability to navigate a digital storefront, willingness to make a payment online, and trust that a product would actually arrive at their doorstep were all very low. This was an era when users were conserving how many apps they downloaded onto their phone due to anxieties over cost/data usage. Given these frictions, these new-to-ecommerce users were hard to acquire digitally and convert all the way through the funnel to a first transaction at an economical customer acquisition cost (CAC) relative to low absolute lifetime values (LTVs).

The reseller model was almost like recruiting a local franchisee who in turn aggregated 20-50 end users. That local entrepreneur could then serve as the last mile ‘sales and customer support’ touchpoint to address end users’ anxieties. This worked on the same principle underlying the success of multi-level marketing (or LIC sales agents).

Order economics – These rural and Tier2+ users didn’t have much spending power and the logistics ecosystem, especially to smaller towns, was nascent at the time. As a result, delivery costs at ₹80+ were enormous as a percentage of the user’s ₹300-₹400 basket size. The reseller model bundled several end user orders together into one shipment to the reseller (amortizing the logistics cost across the sum of those orders), and the reseller then did the last mile distribution themselves. This improved rural order economics substantially.

The exact B2B2C implementation varied from company to company, but they drew on those two core principles. Meesho’s “reseller” model combined both elements, but focused more on customer acquisition benefits (trust was much more of an issue in India than in China, where digital payments were already rampant by the mid-2010s).

PDD’s initial “Team Buying” model didn’t involve a reseller and instead incentivized users to create “teams” to buy products together; the more neighbors they brought into a deal, the larger the discount they were all given. This created inherent virality in the product that led to very attractive customer acquisition economics. This model worked hand-in-hand with PDD’s initial focus on high frequency household goods and packaged foods items, which anyone could be convinced to join in on.

Conversely, Xingsheng’s “community group buying” model was closer to Meesho’s. It involved recruiting a local “community leader” (either a housewife or a local shopkeeper) who would acquire local users, send them promotional offers, provide a local staging area for receiving orders, and then distribute onwards to the end users.

Dope. So how did Meesho go from this reseller focused model to the horizontal e-commerce platform it operates today?

In 2019, Meesho launched a B2C app to enable end users to manage their orders and to browse on their own should they want to. It was meant to be a complementary offering—a way for resellers’ customers to track their purchases more easily. But by mid-2020, they noticed something they hadn’t anticipated: end users who were previously being served by resellers were coming organically to the new app and ordering for themselves.

The users had realized that they could buy the same products they were getting from resellers but with a ~10% discount (since they were circumventing the reseller’s markup). More importantly, COVID had broken through the trust barriers to online transactions—the very barriers that had made the reseller model necessary in the first place. Suddenly, Meesho’s end users were mature enough to buy directly. This was obviously the superior customer experience: customers could browse the fullness of selection available on the platform and were paying lower all-in prices.

The data made the decision clear. By mid-2021, Meesho merged the B2C and reseller apps and the app UX shifted to drive traffic to the B2C flow.

By mid-2022, they’d shut down the reseller side of the business entirely and focused solely on the B2C model. It was a gutsy move—walking away from the model that had gotten them to unicorn status—but Vidit and Sanjeev had always been clear: their mission wasn’t to defend a business model, it was to serve their customers in whatever way worked best.

“Now we have put this as part of our culture code. One of the mantras, we call it ‘Problem-First Mindset’. It comes from this - don’t go with a solution and ask feedback on a solution. Go with a curious mindset to discover the problem.

No one goes and asks ‘hey do you want this?’ Because if you say this, no one says ‘no’. You have to go and ask them what their problems are. So you discover the problems in life. You never go and ask the solution. You ask for the problem, you come back and understand that problem two levels deep, and then you build a solution. So I think one of our big values came from this.

…we care about the problem so much that we end up never caring about the solution that much. The ‘problem’ for us is our mission statement - we have to bring a billion consumers online.”

- Vidit Aatrey on the First Principles podcast (transcript edited for clarity)

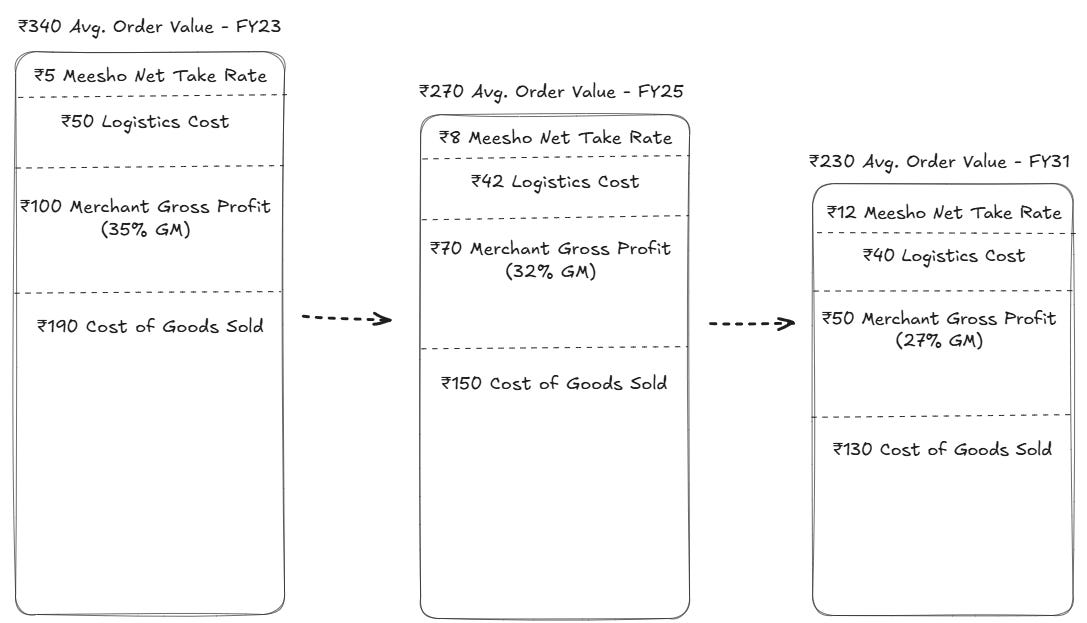

One other important evolution was in Meesho’s commission model. Under the reseller model, resellers were charging a ~10% average markup to end users and Meesho was charging a ~10-15% commission to suppliers as well. This resulted in a ~20-25% all-in markup that the end users bore. As the B2C model took off and users saw the benefit of ~10% lower prices across the marketplace, conversion and retention metrics improved drastically. The ‘North Star’ for the platform became clear to Vidit and Sanjeev: Meesho’s job was to deliver “Every Day Low Prices” on a vast catalog of products and differentiate versus Flipkart and Amazon on value.

To drive prices even lower, Meesho made an even bolder bet: they moved to a zero commission model in mid-2021. This was an aggressive move that could perhaps even have been described as reckless (a Google search will tell you that much of the Indian tech intelligensia wrote off Meesho’s chances of survival after this). The reason is that most marketplaces rely on commissions as their primary revenue stream (eg: Amazon charges its sellers a 15% commission). Meesho was betting they could figure out a different way to monetise. Zero commissions and zero reseller markup positioned them as the platform with the lowest prices in India. This move also set up a flywheel where suppliers had to compete with each other to lower prices to win more organic traffic on the platform.

The zero commission model counterpositioned Meesho versus Flipkart and Amazon, who relied on high commissions in their fashion categories to subsidise thin margins in branded electronics, and thus were slow to match Meesho. This was a learning from Shopee in Southeast Asia, who ran past the incumbent Lazada with a similar tactic (Meesho had briefly launched in Indonesia in 2020 and seen firsthand how much incremental supply Shopee had unlocked with zero commissions). They would make up for zero commissions in other ways (more on this later).

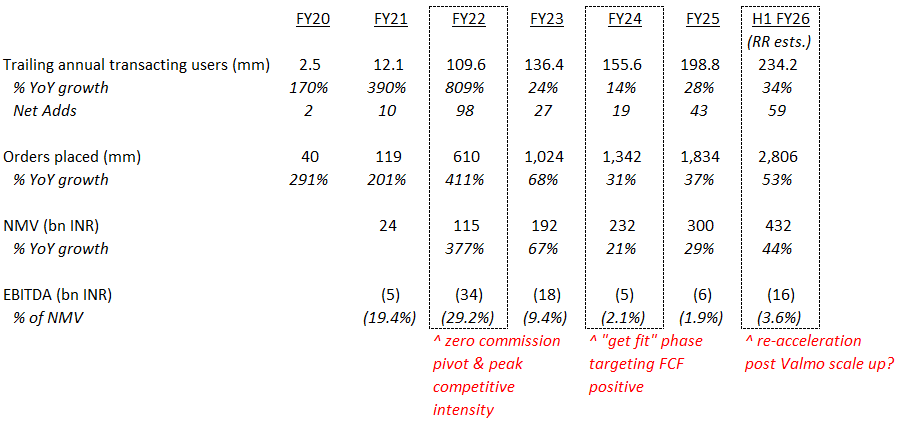

This final iteration of the platform further accelerated the marketplace. Meesho became the most downloaded app in India (and one of the top three shopping apps globally!), and grew 10x in a year from ~12m annual transacting users in 2021 to ~110m in 2022. They raised two mammoth financings in quick succession: a $300m Series E in April 2021 led by Softbank that valued them at over $2 billion, making them India’s first social commerce unicorn, and a $570m Series F in Sept 2021 led by Fidelity and B Capital that more than doubled the valuation to $4.9 billion in just six months.

Thank you for setting the table. What would you say is the throughline that cuts across all these pivots and evolutions?

“Listen Or Die”

Stepping back, rather than a series of “pivots”, the right way to understand Meesho is that they’ve evolved their model in parallel with the evolution of their users. It’s not that the reseller model was troubled; it was in fact growing incredibly quickly with strong cohorts. Rather, their users were not ready for B2C in 2018 but had become ready by 2022. B2C was the better model and they caught their user readiness immediately.

Jeff Bezos has a famous line that “you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time; it’s impossible to imagine a future where a customer says ‘I just wish the prices were a little higher’ or ‘you’d deliver a little more slowly’.” This is a powerful point, but Bezos was also playing on easy mode.

The thing is, the American customer base did not change much between 2005 and 2025 (with regard to income levels, digital savviness, and so on), and so broadly, the same playbook has worked for Amazon across that whole time. The largest changes may have been the shift from first-party to third-party driven supply-side and the shift from third-party logistics and fulfillment to an inhouse model. More recently, Temu and SHEIN’s success in the US do suggest there may be an underserved market at the low-end that Amazon will need to adjust for. Still, these were long arcs that took place over the course of twenty years.

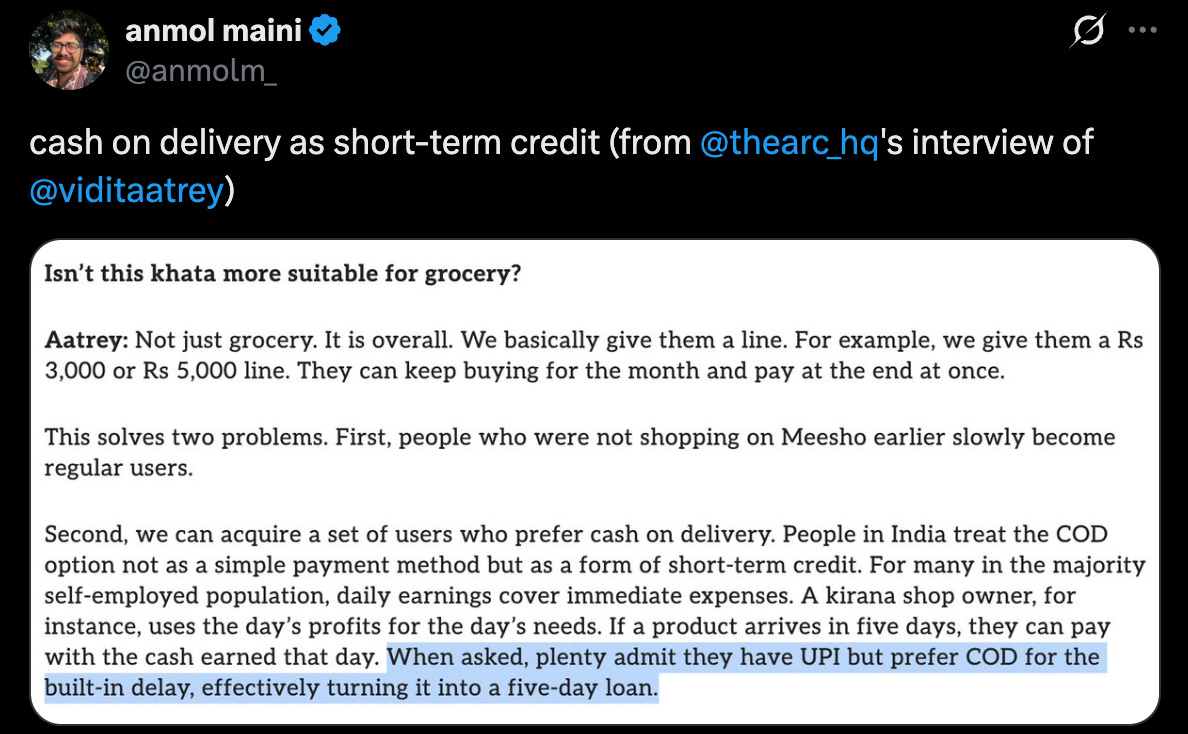

In comparison, the customer changed very rapidly in India. In 2016, most of Meesho’s customers were not even on the internet; in 2019, they had largely gotten cheap smartphones via Jio but were conscious about data usage and uncomfortable with digital transactions; by 2022, post-COVID, they had become digital natives, gotten bank accounts and UPI IDs via the PMJDY scheme, and were transacting online with confidence.

Along the way, their aspirations and discretionary spending power were also growing quickly. That change necessitated a change in Meesho’s model, and only a really customer centric company with a lot of “listening” capability could have picked up on it in real time.

Around the world, most other reseller-focused companies (Dealshare in India, Yunji in China, Facily in Brazil, Super and Kitabeli in Indonesia) – many of whom had raised a lot of venture capital and had reached significant GMV scale – failed to make this change quickly enough and were left behind.

Underpinning this ability to evolve is one of Meesho’s core values - “Listen or Die” (LOD). The idea is to always keep an ear to the ground and understand the perspectives of sellers and customers. Per conversations with former employees, when freshers are hired, they are asked to spend a few days embedded with a seller, serving as an “intern” that helps them improve their businesses. The purpose of this shadowing is to help new tech hires observe how sellers actually interact with the Meesho product and what their daily workflows are.

Similarly, on an ongoing basis, Meesho’s leadership team spends three days per quarter embedded on the ground with their seller communities. This is far from some performative box-ticking exercise. The company genuinely sees this kind of user outreach as critical to their short and long term success. Building user empathy this way is also doubly important given that Meesho’s employees tend to be Metro residents with fairly high incomes and thus are living in a very different world than the Bharat ecosystem that Meesho is trying to serve. When new projects are proposed, employees are expected to ground their pitch in what they heard from their most recent “LOD” trip, buttressed by conversations with users, suppliers, sellers, and other relevant stakeholders in their orbit.

It’s rare to see corporate values instantiated in behavior at this level, and it’s quite clear how this translates into a business that is in tune with the evolving needs of their users. So one thing to keep in the back of your mind as you read the rest of this piece is to think through how the needs of Meesho’s users (and thus how Meesho as a business) will evolve from here.

Noted, sir. So has it been all smooth sailing since the launch of the consumer app in 2021? Was there no response from would-be competitors?

Thank you for the helpful leading question.

After 2021, Meesho’s success finally brought on serious competition from Flipkart, the incumbent with the most overlapping user base (Amazon is mostly Tier 1 focused, while Flipkart has many Tier 2 users). Flipkart moved to a tiered structure with zero commissions on lower Average Selling Price (ASP) items in overlapping categories (e.g. on apparel items below ₹500) and then launched a copycat app called Shopsy in mid-2021 (they were reportedly so frazzled by the rise of Meesho at the time that they reportedly even set up a war room of 20–30 executives to track Meesho’s every move). Shopsy started out as a reseller app and then morphed into a B2C value-oriented marketplace by mid-2022.

Flipkart spent a huge amount on marketing and cut commissions to zero percent across the board on Shopsy. The Shopsy team targeted Meesho’s top sellers and convinced them to also list on Shopsy. Through these tactics, they drove significant downloads – 200+m by mid-2022 and 450+m by mid-2024 – suggesting that they at least succeeded in getting most of Meesho’s users to try the Shopsy product. However, Shopsy ultimately hasn’t made a dent. Meesho in FY25 was ~8x larger than Shopsy on an orders basis. The download numbers looked impressive, but conversion and retention told a different story—Shopsy couldn’t replicate the muscle Meesho had built.

Meesho’s more potent competitor was Shopee. Shopee operates a similar model to Meesho in Southeast Asia and won that e-commerce market outright (i.e. not just the value segment but the premium segment as well) through very aggressive customer acquisition tactics and excellent execution in the 2018-2021 timeframe. In late 2021, with their stock at an all-time high (sitting at >$200bn market cap at the time), Shopee sought to use their supplier base, marketplace knowhow, and balance sheet to enter other emerging markets. Shopee’s parent, Sea Limited, also owned Free Fire, one of the largest mobile games across emerging markets, so there was also a theory that they could leverage the user data and customer acquisition knowhow from Free Fire to attack ecommerce.

They entered both India and Brazil in a very high octane way. In India, they burned nearly $200m on marketing and subsidies in just 6 months, and immediately shot up to become the second most downloaded app in the country. For a brief moment, it looked genuinely threatening.

In mid-2022 however, Indian regulators banned Free Fire from operating in India as a part of a broader crackdown on Chinese-connected businesses operating in India (Shopee is a Singaporean company, but Tencent was a significant shareholder at the time). Given those geopolitical issues as well as the capital markets turning unfavorable towards high burn businesses, Shopee chose to exit India and focus just on Brazil. This was a lucky break for Meesho! Shopee continues to be a potent rival to Mercado Libre in Brazil to this day, and that could have been Meesho’s headache instead.

Amazon dabbled with social commerce in the 2019-2022 timeframe (including acquiring GlowRoad), but didn’t make a serious attempt at the value segment until early 2024 with the launch of an unbranded fashion marketplace called Bazaar. Bazaar is not a separate app but instead a tab inside the main Amazon India app, so it seems to be more of a customer retention lever (to ensure Amazon’s existing customers seeking a value purchase stay within the Amazon ecosystem) versus an outright Meesho competitor. At any rate, our understanding is that Bazaar has not yet reached meaningful scale.

Let’s double click on this for a minute. Despite being very well resourced, why didn’t Shopsy succeed, and why will Amazon likely find it difficult to match Meesho?

Though Flipkart and Amazon have large captive user bases, cross-sell stories have largely not played out in India. Paytm failed to become a super app. Swiggy’s initial integration of Instamart into the core food delivery app was a mistake and ultimately they’ve followed Zomato’s lead in separating quick commerce into a different app. The same seems to be the case for value ecommerce. There are different theories for why this is. One part is behavioral: consumers put each product/app into a specific ‘job to be done’ box, and it’s difficult to break out of the ‘shop for electronics once a year during festive period’ box into the ‘value fashion’ box. Another part is related to internal politics: product teams inside of these companies each have their own OKRs and thus are competing for traffic with one another; this makes it hard for a new product to get enough oxygen to be successful.

The UX for value fashion is very different. Flipkart and Amazon are both ‘search’ oriented experiences, while Meesho is a ‘feed/discovery’ oriented experience (more on this difference later). Despite launching separate apps, both Shopsy and Bazaar are ultimately built on the back-end of their parent entities and thus have limited degrees of freedom to reinvent the product experience. You can’t build a TikTok-style discovery feed on top of Amazon’s search infrastructure—the DNA is all wrong.

Though Shopsy got many of Meesho’s larger sellers onboard through targeted outreach, they were unable to replicate Meesho’s reach with smaller sellers. The long tail mattered, and Meesho had spent years building trust and tools for sellers who’d never sold online before.

The logistics networks that Flipkart and Amazon built were geared towards delivering quickly to Metro and Tier 1 city customers. This network is too expensive for the value fashion use case, which requires a different first mile (picking up from fragmented sellers) and a different last mile (dropping off in smaller towns where there may not be enough density for a delivery hub). Their cost structures were fundamentally misaligned with the unit economics of a ₹200 order.

After the ‘Value Commerce Wars’ were over, Meesho entered a period of retrenchment where the focus became efficiency, with a few key initiatives: (i) bringing down cost-to-deliver via Valmo, their inhouse logistics network, to unlock lower average selling price (ASP) products for their customers; (ii) bringing down overhead costs to get to Free Cashflow (FCF) positive; (iii) increasing take rates via deeper investments in the advertising stack. This included a layoff in mid-2023 of ~15% of the workforce, which Vidit attributed to “judgement errors in over-hiring ahead of the curve.” These levers came together to bring EBITDA losses down significantly and reach FCF positive by FY24 (notable because Meesho operates on a significantly negative working capital cycle).

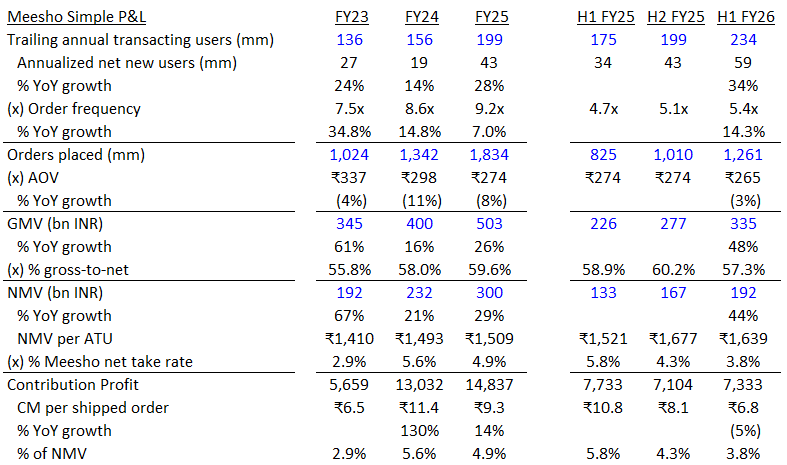

We can see these two phases – hyper growth and then optimisation – play out in Meesho’s financials. From FY21 to FY22, users grew 10x, NMV grew 4x, and losses widened from ~$60m to ~$420m. In FY23 and FY24, losses in turn came down significantly while growth decelerated. In FY25 and FY26, growth has impressively accelerated again, this time at scale. The ability to re-accelerate growth after a period of cost-cutting is rare—most companies that tighten can’t regain momentum.

Note that Meesho management’s preferred topline metric is “Net Merchandise Value” or NMV. NMV is the value of all products successfully delivered to customers, inclusive of GST but excluding cancelled or returned items and excluding any discounts applied at checkout. Said more simply, NMV represents the amount that consumers are actually spending on Meesho and is a more conservative figure than GMV (which is prior to returns).

Right, maybe we can switch gears now. Can you give us a snapshot of Meesho today?

Sure, let’s start with their buyers and sellers.

Buyers:

234m Annual Transacting Users (ATUs) each placing ~10 orders annually. To put that in context, that’s roughly one in five Indian adults shopping on Meesho nearly once a month—a penetration rate that puts it in the league of very few truly ‘population scale’ platforms in India.

88% are from towns outside India’s eight Metros. This isn’t an India1 story.

54% are women. This matters because women typically control household purchasing decisions in these segments, and building trust with them compounds across categories.

Sellers:

~700k Annual Transacting Sellers, each selling ~3,500 orders annually on average. That’s about 10 orders per day per seller—enough to be meaningful income, but not so much that it requires sophisticated operations.

~40-50% of sellers are new to selling on e-commerce (i.e. Meesho has brought them online); previously they would have been selling via small shops in a city market. Meesho has become the first step online for hundreds of thousands of small businesses in India.

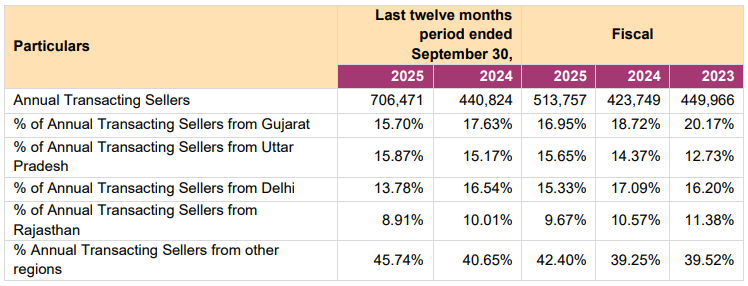

These are largely SME factories or wholesalers in specialised manufacturing clusters, like Surat for sarees, Tirupur for knitwear, Agra for leather goods, Morbi for ceramics, and so on; there’s a concentration in sellers from Gujarat but otherwise it’s reasonably dispersed. These clusters are where India’s unbranded manufacturing lives—family-run operations that have been making the same products for decades, now getting direct access to consumers for the first time.

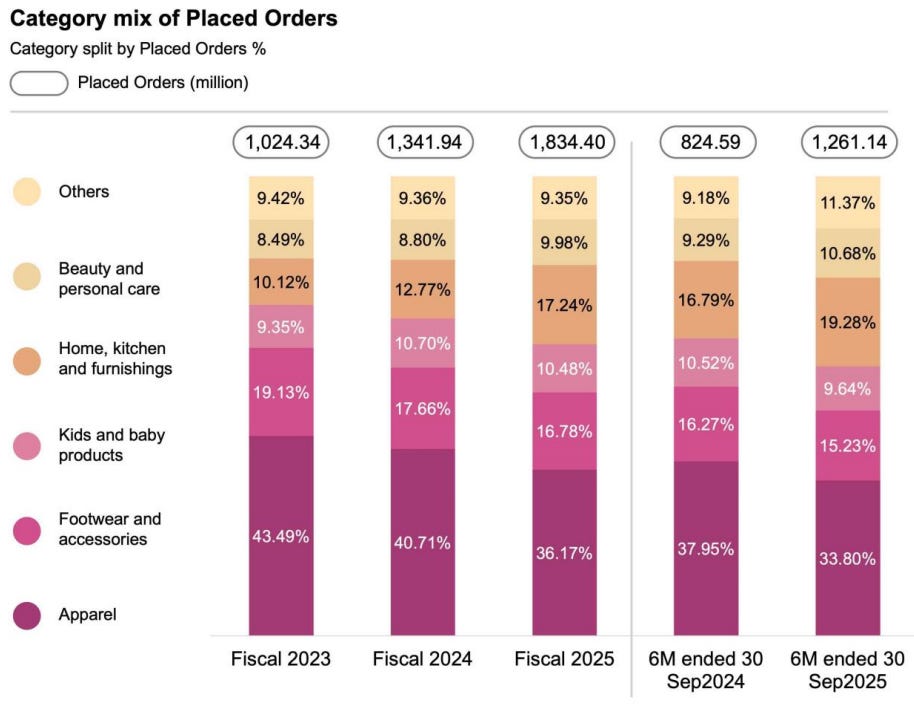

What’s being sold? What are the categories?

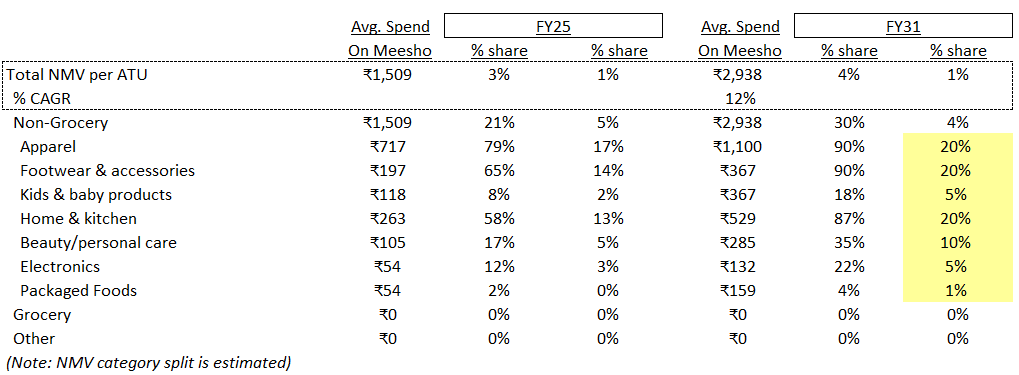

Meesho is largely focused on unbranded products in categories where long-tail selection matters: apparel, home & kitchen, beauty, packaged foods, and so on. Below is a split of orders by category provided in the DRHP.

Across these categories, Meesho offers on average ~154m products daily to its users! To put that number in perspective, that’s roughly 300x the number of SKUs in a large supermarket, refreshing every single day. Meesho started largely focused on apparel and footwear, but those categories are now less than half of total orders (though they are still more than half of total NMV given that AOVs in apparel are 1.5-2x higher than in the newer categories). The category mix shift tells the story of Meesho’s evolution from fashion marketplace to everyday commerce platform:

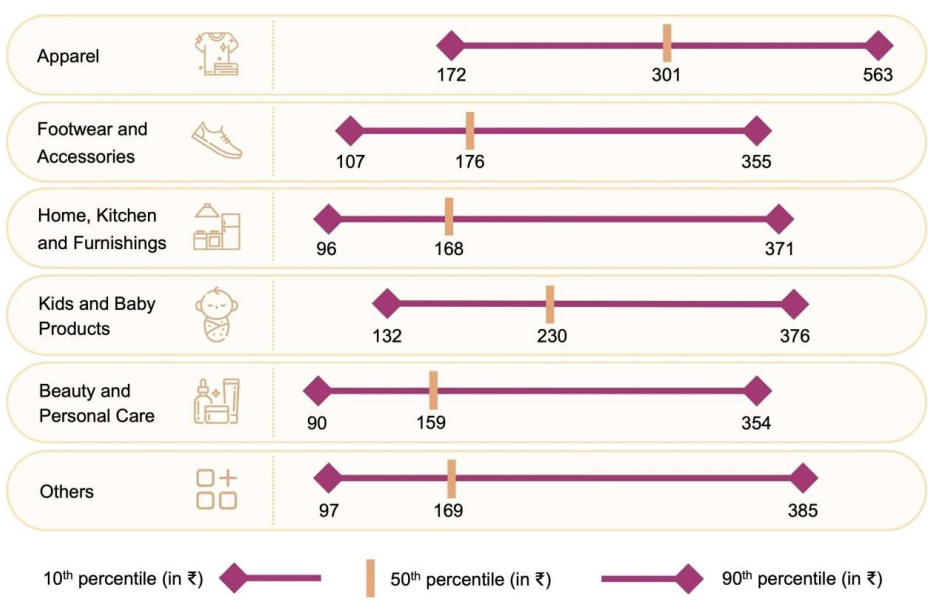

To give you a sense of the price points on the platform, here are the 10th percentile, median, and 90th percentile prices for products sold on Meesho:

Even at the 90th percentile, prices remain remarkably low compared to what you’d find on Amazon or Flipkart. There is affordability built into every tier.

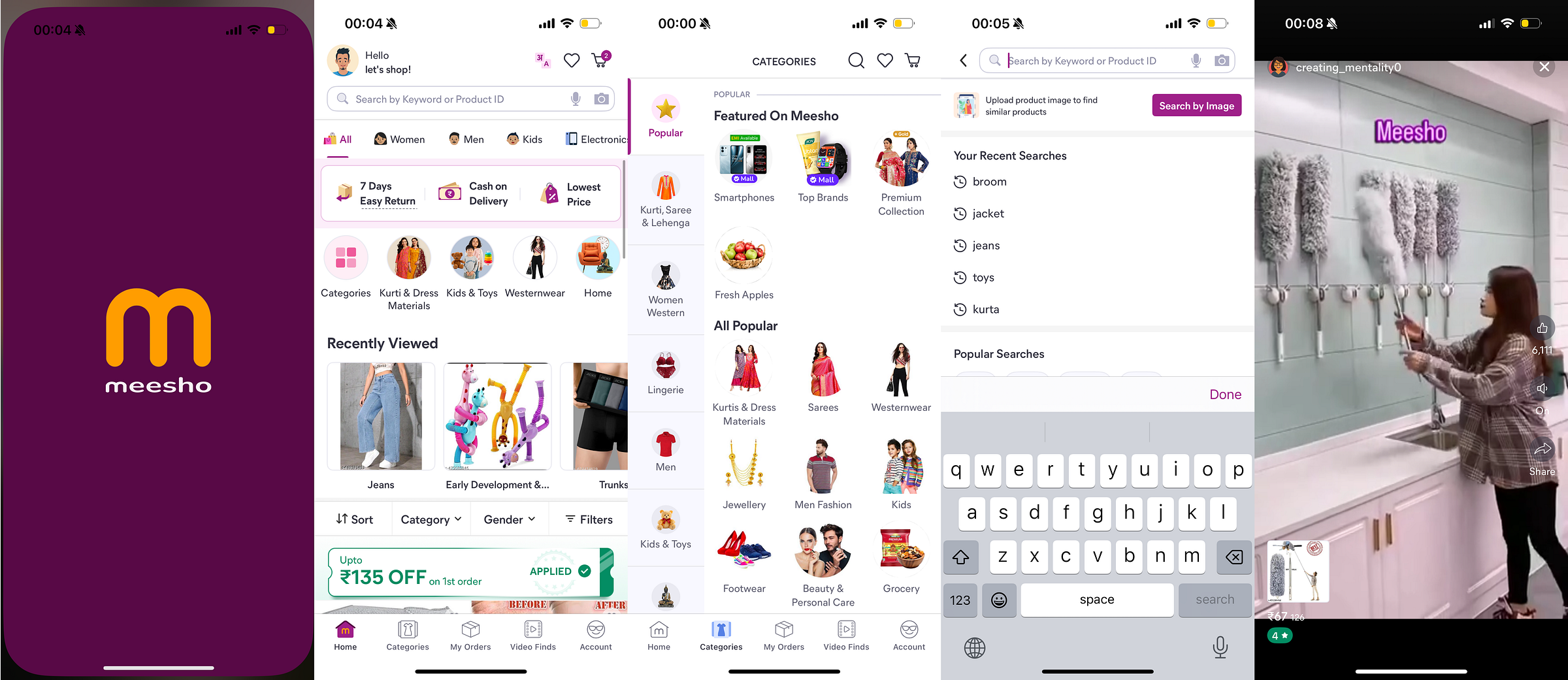

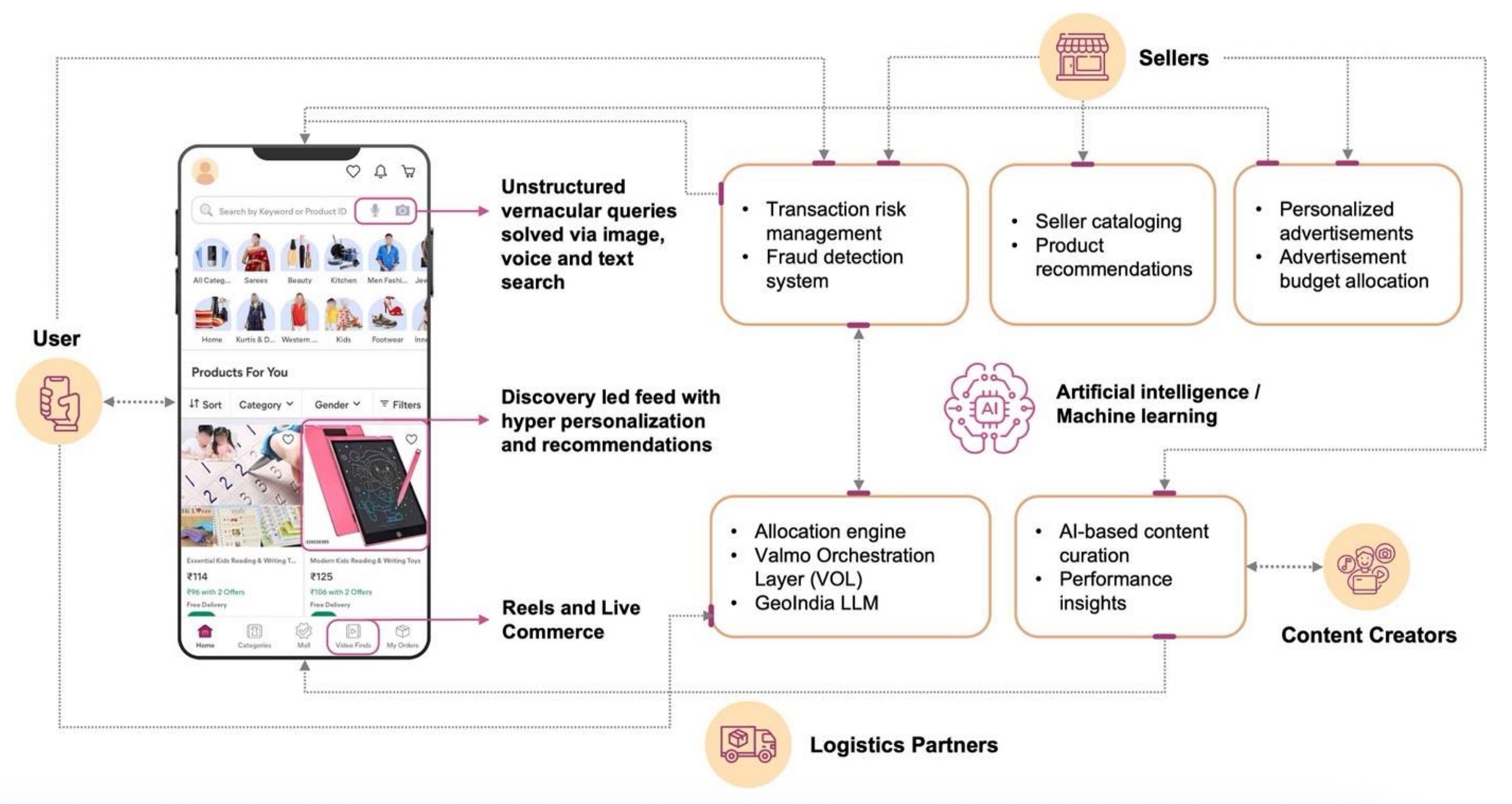

What’s the actual user experience?

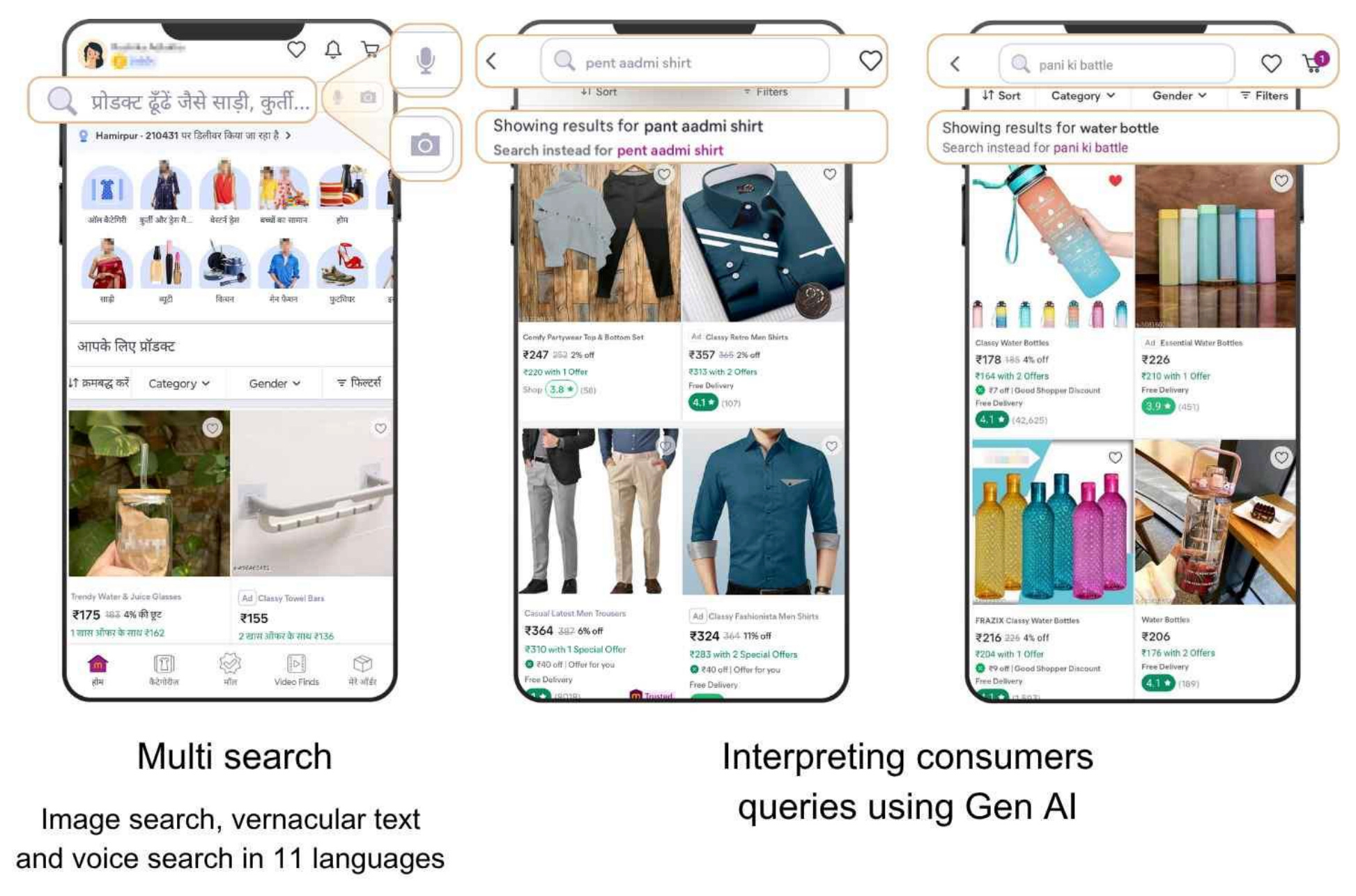

Meesho is a discovery-based feed. 73% of all orders came via their discovery feed and algorithmic recommendations, not via search.

There are a bunch of reasons for this:

The product started as a fashion app and continues to be focused on long-tail soft goods categories; these are inherently ‘browse not search’ categories where a customer typically navigates to the broad category they want and then starts scrolling. This maps to the way customers shop offline: they walk through stalls and look for something that catches their eye rather than walking into a store and asking for a specific item. Meesho’s feed is a digital version of that natural behavior. It’s replicating the bazaar experience digitally where the joy is in stumbling upon something, not hunting for something specific.

The Tier 2-4 user base is not comfortable with search as a modality (they may not know the exact name of the product they’re looking for). Even if they do search, it’s often via voice or image search (uploading a screenshot from social media) rather than typing out the product name. Many of Meesho’s users are shopping in languages where typing is cumbersome, or they’re navigating an app in English while thinking in Hindi, Tamil, or Gujarati. The feed helps to remove some of that friction.

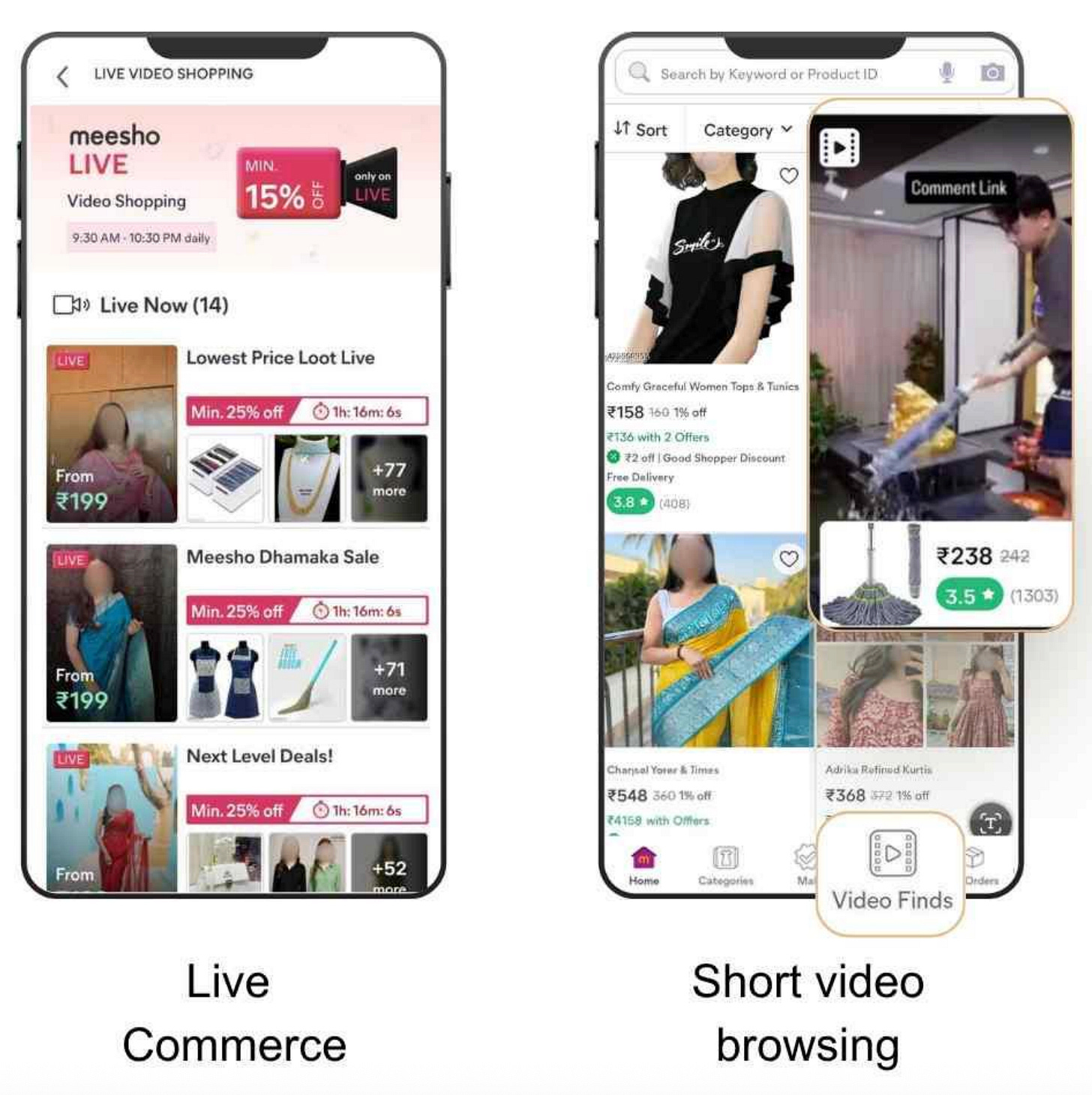

Browsing itself, especially now that it has been enriched with user-generated and influencer video content, is a source of entertainment for these users. Meesho’s users spend on average ~10-15 minutes daily in the app, which is 10-40% more than competitors. The experience is more habitual than transactional, more akin to scrolling Instagram than visiting a store.

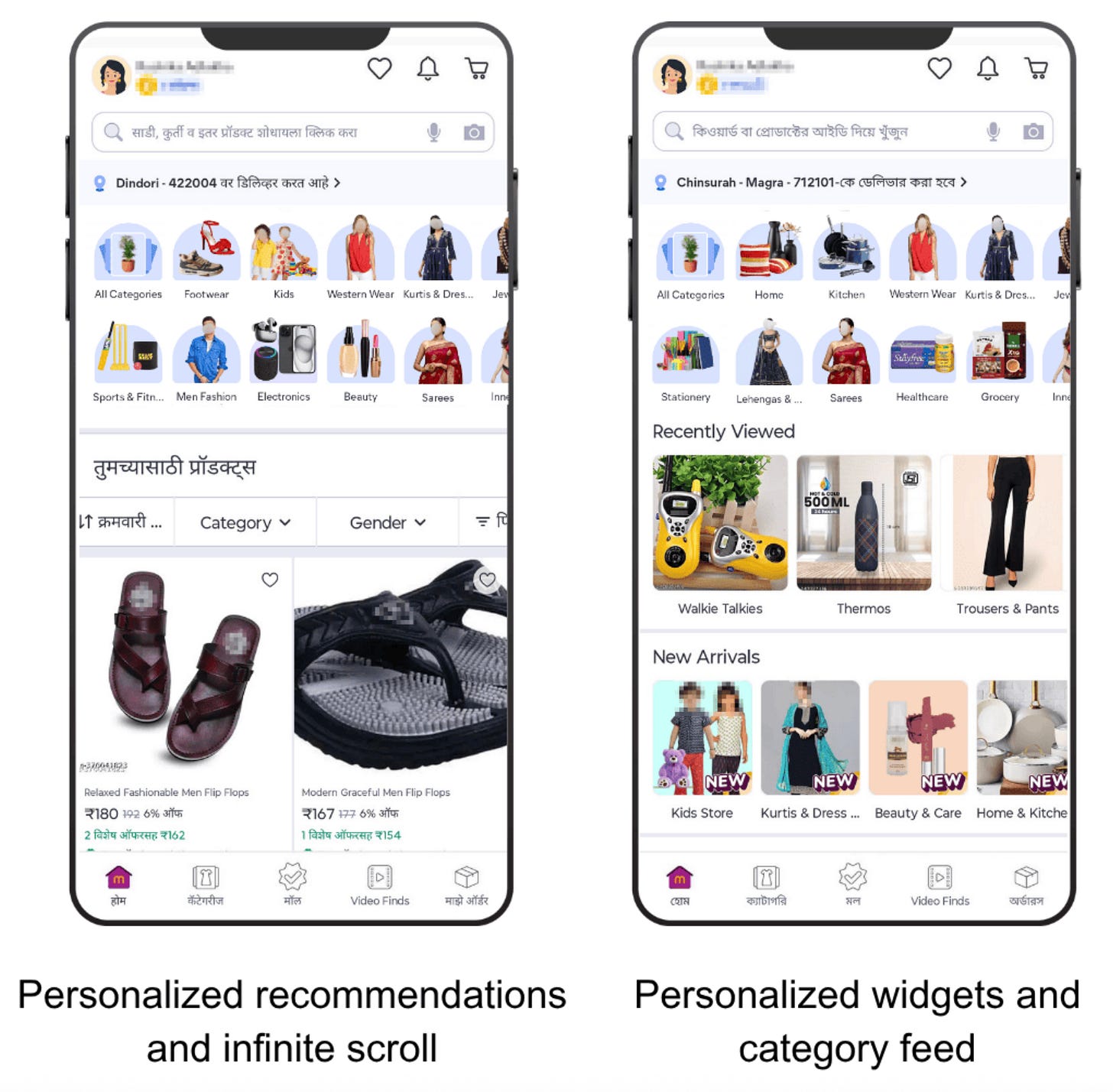

Meesho’s demand is very unstructured. When a user opens up the app, they are presented with a set of relevant products in their feed. If they navigate to a particular category, toggle a filter, or search for something simple like “red kurta”, that additional intent data percolates into what is shown in the feed in real-time.

This demand is also more impulsive than a search-first platform like Flipkart. Rather than logging on with the specific goals of purchasing a red t-shirt and replacing a toothbrush, the user spends time daily on the platform just scrolling and hanging out. It’s not a guarantee that they end up liking or purchasing something. We can see this in very low multi-unit order rates (Meesho’s units per basket are just ~1.2); users tend not to craft pre-meditated baskets.

Note that Meesho’s understanding of a user’s intent improves the longer the user spends on the platform and the more orders they place (and return). Through these interactions on the platform, Meesho figures out each user’s gender, size, preferred aesthetic (ethnic v. western; flashy v. simple), preferred position on the price-quality spectrum (two peoples’ opinion on “good enough” quality will vary significantly), etc. This is a strong, compounding competitive advantage.

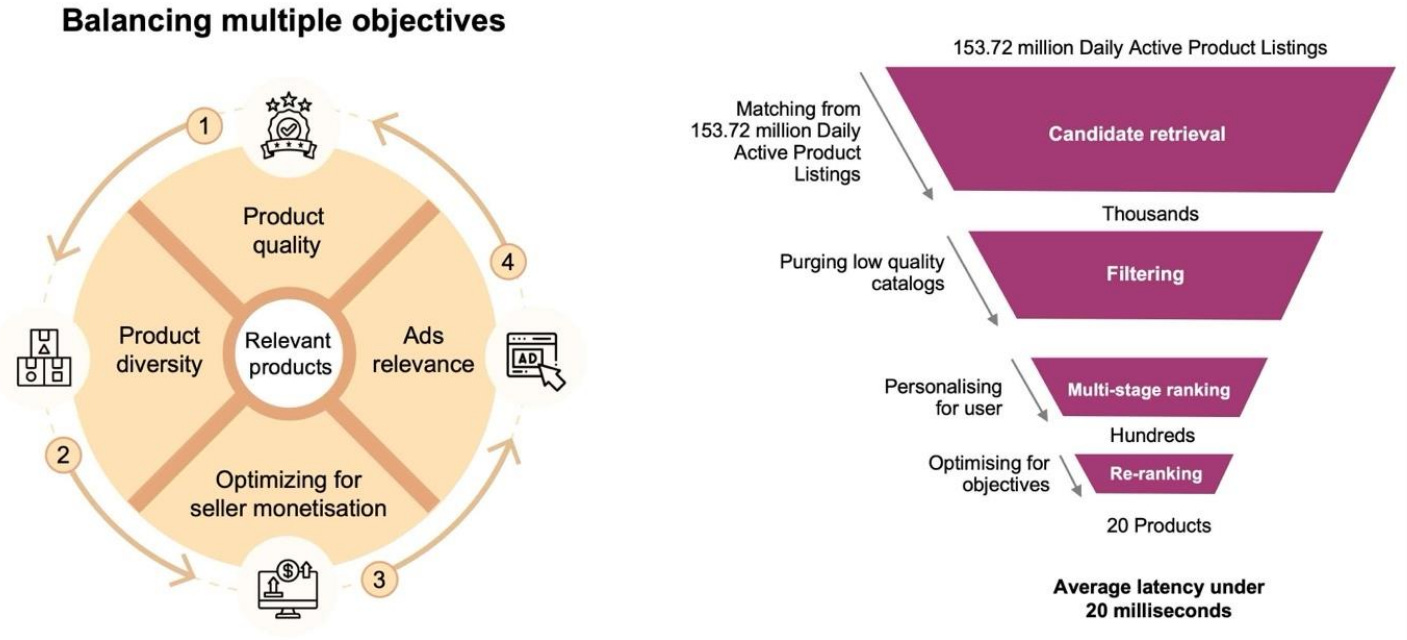

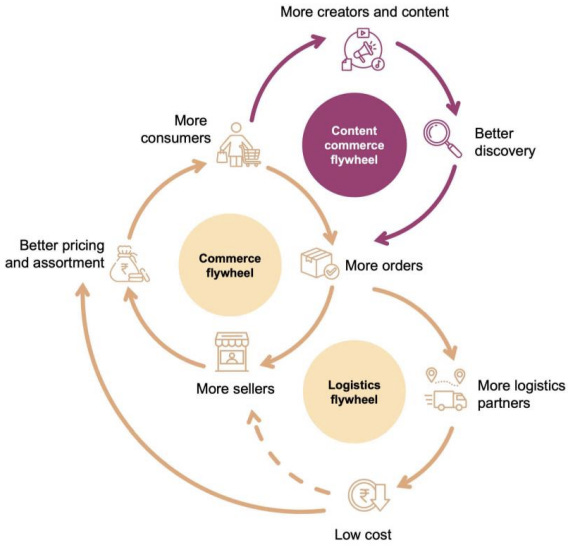

The data flywheel is spinning faster with every transaction. The more browsing and ordering activity on Meesho, the better Meesho’s product relevance algorithm gets, which in turn improves the quality of the feed for users and increases engagement and conversion rates, which produces more data, and so on. (The quality of these predictions should improve with the application of more compute, and so in that sense, Meesho is a big beneficiary of recent advances in GPUs).

All this means is that even if a new entrant were to spend aggressively to acquire Meesho’s users, those users would have a worse initial experience as the new platform wouldn’t know what to show them. You can copy the app, but you can’t copy the algorithm’s understanding of 234 million users’ preferences built over years of interaction.

So that’s the Demand side. What about the Supply side?

The supply side is equally unstructured. Meesho has a very lightweight seller onboarding flow (they recently successfully lobbied to onboard sellers without GST, opening the door to India’s vast unorganized manufacturing sector). Sellers can operate their stores entirely from their mobiles, taking simple phone camera pictures of their merchandise (which Meesho then cleans up with AI) that are uploaded as SKUs, and supplementing that with a basic description. Meesho guides them to enhance their listings with product details, tags, and better photos, but high production values aren’t required. Their philosophy is simple: requiring high-quality photography—or privileging it in the ranking algorithm, which amounts to the same thing—is a tax on suppliers that gets passed to customers. The same applies to demanding detailed listing information. As a result, Meesho’s initial context on each listing is sparse, and there are literally hundreds of millions of listings to parse through.

This creates a fundamentally different problem than traditional e-commerce. Meesho has to solve a hard matching problem between unstructured demand and unstructured supply in near real-time. It’s closer to the challenge of shortform video (TikTok) or feed advertising (Instagram, YouTube) than to commerce, which typically relies on high-intent search queries to drive rankings.

Meesho solves this by gathering data systematically. Each new listing is shown to a statistically significant number of users. Their on-platform behaviour—whether they scroll past or dwell, what percentage of click-throughs convert to baskets—and downstream behavior (return rates, reviews) signal whether that listing deserves more or less visibility. Underperforming listings are deprioritised in the algorithm, and sellers receive feedback on which additional catalog information might help or how much their sales would improve if they lowered prices. This is a democratic approach to platform commerce where each listing gets a fair shake.

The numbers bear this out. Per the DRHP, the average number of days for a new seller to receive their first order after listing a product on Meesho decreased from 32 days in Fiscal 2023 to 26 days in Fiscal 2024 and 16 days in Fiscal 2025. Halving the time to first sale matters enormously for a small manufacturer testing whether online commerce actually works. This fast path to initial sales increases sellers’ willingness to stick with Meesho and learn how to be successful on the platform. Contrast this with Flipkart or Amazon, who prioritize large sellers with established review data in their search results—creating an implicit barrier to entry that new sellers can only overcome by spending on advertising until reviews accumulate.

Each user’s feed balances “exploit” matches (products Meesho is confident will resonate) and “explore” matches (products Meesho wants to test, both to understand the product and the user’s preferences). Meesho calibrates the mix to maintain high conversion rates while also gathering data on new listings. With highly engaged customers unlikely to churn, they can show more “explore” products, effectively using power users to train the algorithm.

Is the overall approach very different to other leading e-commerce players?

Meesho’s approach is very different from Amazon’s and Flipkart’s. For the latter, both demand and supply are more structured, with a power law around the top selling SKUs in each category.

This stems from their roots in consumer electronics and particularly handsets, where the top twenty SKUs drive most of a category’s sales. On the demand side, they are largely search-driven platforms that rely on intent signals from keywords or SEO/affiliate/SEM hyperlinks to determine what to show customers. Those keywords are often branded (”boAt” or “Louis Philippe shirt”).

On the supply side, their history of owning inventory has imprinted itself in their cultural DNA, leaving them with a traditional retailing approach to merchandising. In practice, this means category teams place bets on which products or brands will be in demand based on their assessment of consumer trends. Those teams then work with manufacturers to secure the right supply at the right prices, including via large private label programs. This creates distorted incentives where the marketplace may need to direct traffic towards inventory held by manufacturing partners who were promised a certain level of sales (or to liquidate inventory on the platform’s own balance sheet). Meesho’s algorithm has a simpler objective function —show users what they want to see, not what needs to be sold.

Meesho’s other core differentiation versus Amazon and Flipkart is their approach to logistics.

Logistics? This one is kind of a big deal right?

Yup.

Early on, Meesho realised that their user base would prefer a ₹20 order discount over two-day delivery, so they chose to use slower but cheaper delivery methods (while giving users an option to pay more for faster deliveries). To do this, they leveraged low cost third-party logistics providers like Delhivery, Ecom Express, and XpressBees, while Amazon and Flipkart were vertically-integrating to offer faster and faster deliveries. They became the largest customer of each of these 3PLs (comprising 25-30% of Delhivery’s revenues in the relevant segment and >60-70% for Ecom Express and XpressBees), resulting in significant negotiating leverage to push prices down.

Then, in FY23, they changed their approach, deciding to incubate an inhouse logistics platform, albeit with an asset-light model. This was Valmo. Valmo is a technology orchestration layer that stitches together individual logistics players across the first mile, mid mile, and last mile to create a synthetic 3PL network.

The model is elegantly simple: a local truck owner signs up, is told to pick up packages from points A and B (scanning them in via a phone app), and drop them off at local hub C. The local hub itself is operated by a local franchisee who sorts packages, again via instructions from the Valmo app. A larger truck owner is then told to pick up a set of packages at hub C and drive them to another city to sortation center D (which is operated by yet another third-party, albeit likely a larger one). This chain of hand-offs continues until the package reaches the end customer. The average Valmo order is handed off between 4-5 intermediaries.

The premise behind Valmo is twofold: (i) there is abundant latent unorganized logistics capacity in India (the B2C logistics market is still a fraction of the B2B market) that is underutilised and can be leveraged by Meesho at very low cost; (ii) Meesho users’ low delivery time sensitivity means Meesho can pursue a unique network design that prioritises utilisation above all else (for example, holding a truck overnight at the origin until it’s full). By contrast, their 3PL partners are serving a mix of clients and thus are not optimized solely for cost.

To illustrate the difference between unorganized and organized truckers and how Meesho derives a cost advantage from aggregating the former, here are a few sources of savings:

Unorganized trucks may just be lying idle and thus be willing to accept a lower daily rate. Similarly, local delivery hubs may simply be a portion of a local workshop that was unutilized.

Typical to other unorganized service providers, Valmo’s vendors have less overheads and may be operating fully depreciated trucks. There are also grey market dynamics at play. Meesho’s ‘franchisees’ may not be as stringent on compliances (for example, a shopkeeper’s son may make deliveries without being a formal employee; they may drive a vehicle that doesn’t meet emissions standards or overload a truck).

Competitors may impose unnecessary requirements. For example, Amazon requires each of their truckers to install an automated lock that only releases when the truck reaches its destination. This is expensive for the trucker, but reduces pilferage. That trade off is worth it when you’re delivering iPhones but not for low-cost clothing. Amazon also has aesthetic requirements. Their trucks can’t be too old, the drivers need to wear shoes (for safety reasons), they need to wear a uniform, and so on. This all adds cost.

Still, Valmo’s asset-light approach is not a panacea and the network will need to make capital investments over time. The unorganised market has a very high cost of capital, so any investments (from small ones like automated locks to mid-sized ones like 46-foot tractor trailers to large ones like sort center automation) that are pushed onto franchisee balance sheets will be more costly for Valmo than for a scaled player with access to debt capital like Delhivery. ‘Asset light’ does not obviate the network’s need for assets! Without automation in particular, Meesho’s network is more at risk of inflation (especially wage inflation) than Delhivery’s. It is also more at risk of bottlenecking during seasonal peaks (an automated sort center can process 10x more parcels in a fixed plot of land than a manual operation).

The solution over time for Valmo will likely be to partner with large franchisees, at least for the mid-mile, and to help arrange financing for them (by backstopping them in some fashion). This is how Cainaio, Alibaba’s logistics arm (which, similar to Valmo, is an aggregation of smaller 3PLs), scaled.

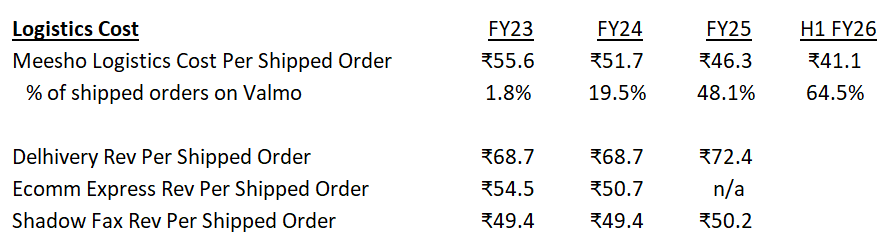

The results have been remarkable. Less than three years after its launch, Valmo has ramped up to serve 67% of Meesho’s total orders as of Sept 2025. This will amount to >1.5bn parcels in FY26, moving Valmo past Delhivery as India’s largest parcel delivery network by volume. Logistics cost per shipped order has come down for Meesho by ~25% from ~₹55 in FY22 to ~₹45 in FY25 to ~₹41 in H1 FY26. This is particularly impressive given they’ve had to outpace underlying wage and fuel inflation. Some of this may also be attributable to mix (shipping costs decrease with package weight and Meesho’s new categories like beauty are lighter weight), but Valmo is the primary driver of the cost savings.

How do we contextualize those numbers?

It’s hard to compare apples-to-apples adjusting for shipping speed (Meesho ships slower than others), parcel type (for example, Delhivery has a large business shipping consumer durables and appliances, which skews their numbers significantly), and origin-destination mix (Meesho ships to smaller towns, which should be more expensive than to a metro). Still, if we were to put Valmo’s numbers next to the other 3PLs, they stand out as impressive. Valmo is cheaper than Ecomm Express and Shadowfax’s revenue per order (part of the savings comes from not paying the mark up above their costs that the 3PLs have to add to cover their fixed costs and capex needs).

Beyond just reducing logistics costs, Valmo creates additional value for Meesho by unlocking new categories and price points that were previously uneconomic to serve, which broadens Meesho’s addressable market.

Think about the distribution of average selling prices of all retail products in India. In order for a product to be saleable online, the seller needs sufficient profit after logistics costs to cover their overheads and cost of capital. Illustratively, to cover ₹50 logistics cost plus overheads, a seller may need to generate ₹60 of gross profit. At ~30% gross margin, this would necessitate a minimum ₹200 selling price for a product to be viable. At ₹40 logistics cost, the seller would only need to generate ₹50 of gross profit, bringing the minimum price down to ₹165. Small reductions in logistics cost thus unlock many new categories.

This supply-side elasticity is the more important effect than demand-side elasticity. Meesho’s growth has not accelerated because Valmo is lowering like-for-like prices for customers (a ₹10 reduction in delivery costs on a ₹300 base AOV is just 3% savings), though that is happening. The bigger driver is that Valmo has enabled sellers to add new inventory to the marketplace at the ₹150-₹200 price point, which has enabled Meesho to capture new consumption occasions.

We see this dynamic playing out in Meesho’s numbers. Since Valmo’s launch, delivery costs have come down by ₹15, but AOVs on the platform have come down by ₹60 as they’ve grown quickly in low Average Selling Price (ASP) categories like home goods and beauty (where median AOVs are ~₹170, versus ₹300 for fashion). Annual order frequency is also up more than 40% from ~7.5x in FY23 to nearly ~11x in H1 FY26.

All that said, there are some important caveats regarding Valmo:

First, there’s a debate to be had around resource allocation. At this stage in the company’s journey, a project like Valmo has to compete for resources with many other important initiatives — one could argue they could have gotten to Valmo later on (Alibaba didn’t start working on Cainaio until 2013, when they were doing >$160bn of GMV!). The Valmo bet makes sense if these cost savings were only achievable through Meesho owning its own destiny on logistics (versus in partnership with the 3PLs to create a low cost network).

Second, while logistics costs have come down, delivery success rates have declined. The delivery success rate for cash-on-delivery orders has decreased from 78.6% in FY24 to 77.7% in FY25 to 75.9% in H1 FY26. The reasons for this aren’t immediately clear from the public disclosures. Lower AOV items typically have lower return rates, and Meesho is mixing away from apparel, which tends to have the highest return rates. One possibility is that deeper penetration into newer, more price-sensitive customer segments—who may be testing e-commerce for the first time—results in higher rejection rates at delivery. Another could be the growing share of impulse purchases driven by the discovery feed, which may lead to more buyer’s remorse. This could also be caused by a degradation in delivery times, which is the likely other side of the coin to Valmo’s cost savings; each day an order is delayed, the more likely the customer is to change their mind. The DRHP doesn’t provide data on how delivery times have evolved, making it difficult to assess whether speed is a contributing factor.

Third, many of Valmo’s costs sit on their logistics partners’ P&Ls, and there’s a question of whether those partners are making enough money to sustain the model. Meesho contends that the efficiencies come from density, smart routing, and predictable volumes rather than pricing pressure, and that partners benefit from steady throughput and faster payouts. Still, questions remain about whether those vendors are earning an adequate return on capital to justify continued investment in the network. If Valmo’s cost savings ultimately prove unsustainable, the cost structure could face pressure.

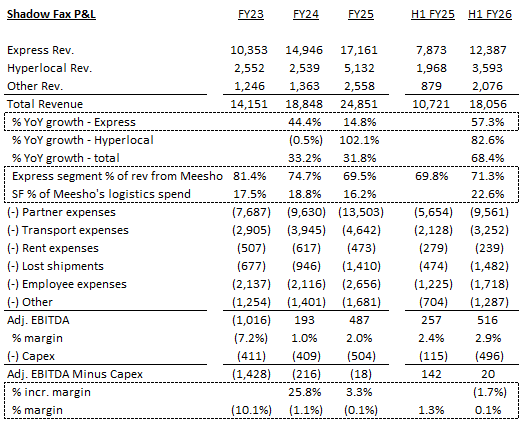

Shadowfax’s DRHP has come out recently, and they earn ~70% of their express segment revenues from Meesho, so we can use them as a proxy for the economics of Valmo’s supplier base. Unfortunately, they don’t separate out the express segment’s profitability, but even at the overall EBITDA level, Shadowfax is only barely breakeven with very low incremental margins despite growing very quickly alongside Valmo. It will be difficult for Shadowfax to sustainably fund the growth capex needed to scale their network at these margin levels (though they operate an asset light model, there is still a growing capex requirement; they are intending to spend >₹100 crs on capex in each of FY26 and FY27). Note also that the ‘lost shipments’ line item has exploded from ~6.5% of express revenues in FY23 to ~12% in H1 FY26. Shadowfax may need ₹2-₹4/order more from Valmo to operate sustainably, which would knock off ~20% of the cumulative savings Valmo has driven so far.

Helpful. Now let’s get to the spicy stuff. How does Meesho make money?

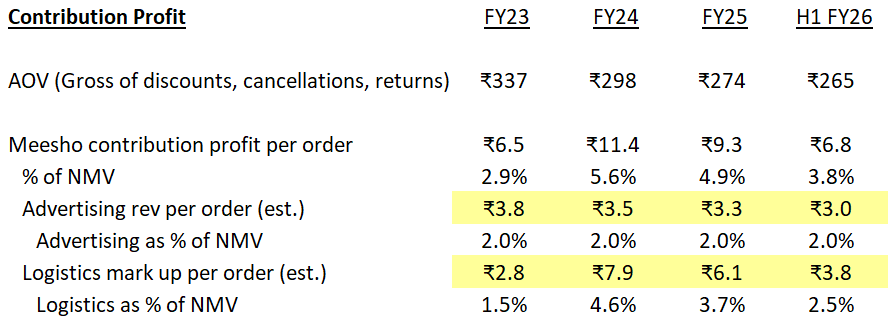

Given there’s no commission, Meesho today monetizes in two ways: (i) advertising; (ii) a markup on the underlying logistics cost. They don’t disclose the split of contribution profit between the two, but our estimate is that contribution profit is split roughly half-half between advertising and logistics.

Advertising

Conceptually, advertising on Meesho works similarly to other ecommerce marketplaces: advertisers spend money to drive incremental sales. With thousands of sellers competing in each product category, the platform has significant power to steer consumer attention. A portion of the listings shown in the feed are ‘organic’ (listings the algorithm deems most relevant to the consumer) and a portion are ‘paid’ (listings auctioned off to the highest bidder). The magic of the digital ads model is that the highest bidder should be the seller best positioned to monetize that particular impression—typically one offering a highly relevant product (driving high conversion rates) with high gross margins (enabling them to spend a significant percentage of gross profit on the ad). This means the ads blend in well and don’t detract from the customer experience too much (as we’ve all experienced on our Instagram feeds).

In the unbranded segment that Meesho focuses on, there’s a unique interplay between how much a seller chooses to spend on advertising and the prices they list products at. Consider a seller whose product cost is ₹150. They can either list at ₹250 and spend 10% of the AOV (₹25) on advertising, or simply list at ₹225 with no ad spend. How much the marketplace rewards lower prices in its algorithm determines which strategy maximizes profit. Today, Meesho is largely focused on user growth and thus incentivizes merchants to lower prices rather than spend on ads, but that balance can evolve over time (and be managed category by category). Meesho’s control over that dial is part of why we are confident they can increase advertising take rates over time.

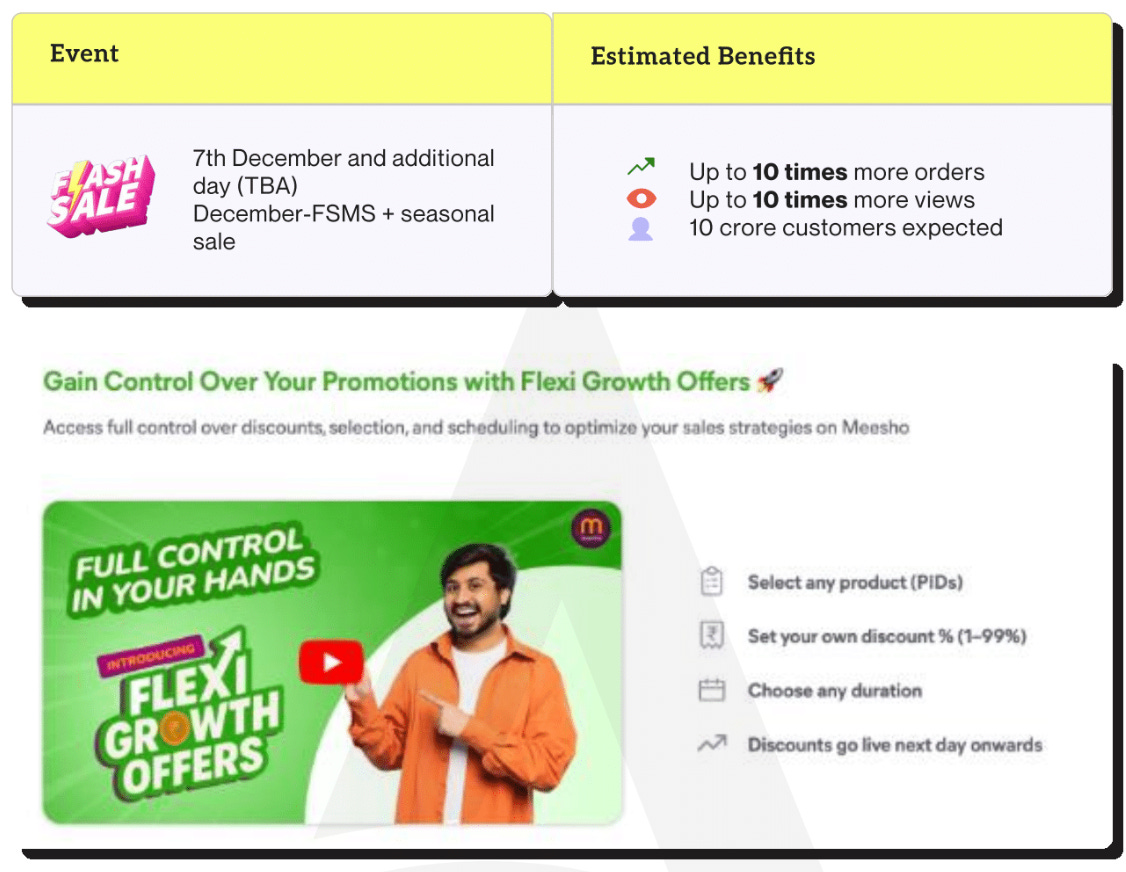

Below are examples of Meesho’s promotional nudges to sellers (courtesy of The Arc):

Logistics

Meesho runs logistics as a profit center. Think of the platform as negotiating with logistics providers on behalf of all sellers, securing rates significantly below what individual merchants would get going direct to a 3PL, then keeping some of those savings. Again, there’s a decision to be made around elasticity. Every rupee Meesho charges the merchant above the logistics cost gets passed on to the consumer. Right now, Meesho’s choice seems to be keeping ~₹5-₹7 per order as logistics contribution profit and passing all remaining efficiencies onwards. This too is a dial that can be adjusted, but we think Meesho will pass on any further savings from Valmo rather than keeping them as additional profits.

Got it. What do their financials really look like?

Let’s start with the Historical numbers

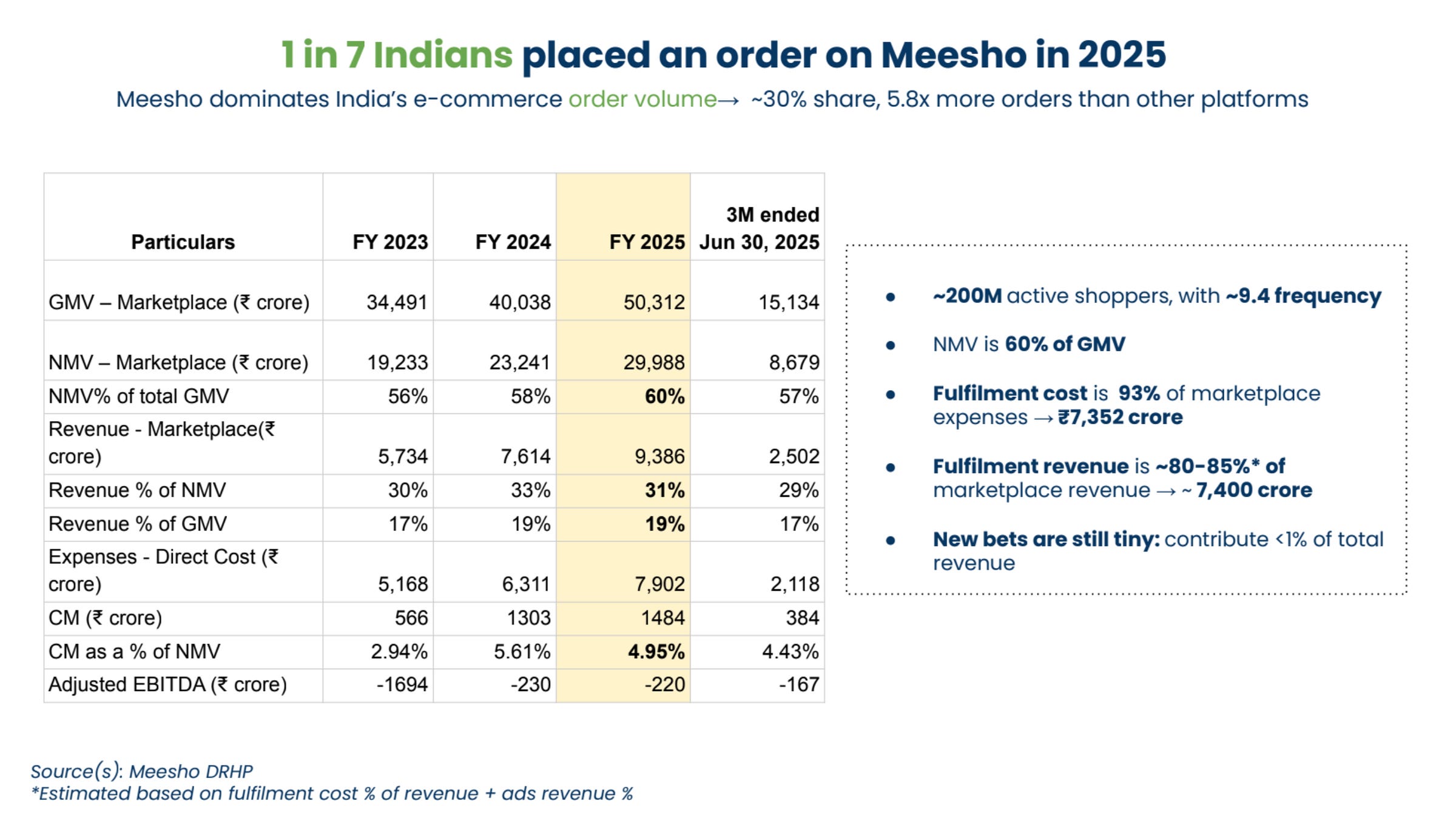

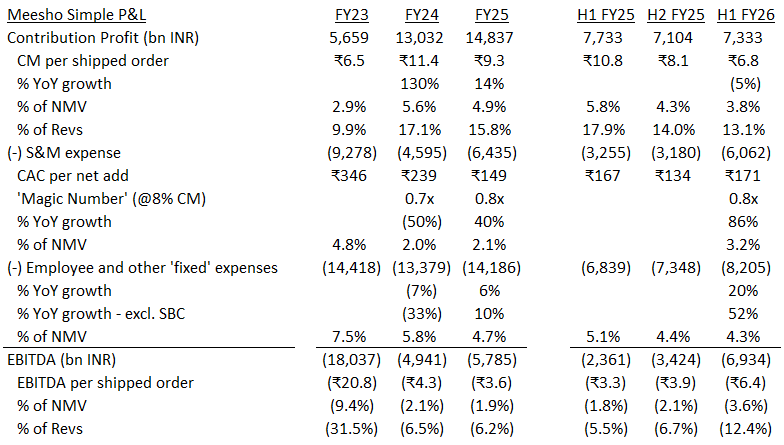

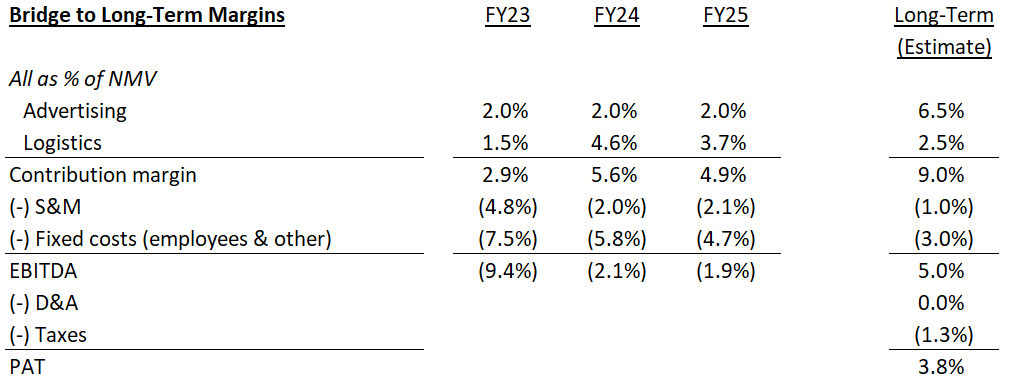

Putting all that together, below is a snapshot of Meesho’s P&L over the last four years:

Meesho has grown transacting users at ~20-25% CAGR while those users have increased their order frequency from ~5.5x annually to ~10x annually, translating to a ~45% CAGR in orders placed on the platform. Average order value has declined at an ~8% CAGR (for reasons we discussed earlier), resulting in a mid-30s CAGR in GMV. Total gross-to-net has improved slightly (largely due to less discounting on the platform, though delivery success rates have declined slightly and returns rates have been stable), translating to a modestly higher growth in NMV than in GMV. Notably, Meesho actually accelerated in FY25 and again in FY26—orders grew 53% YoY and NMV grew 44% YoY in H1 FY26.

Reported revenue is not a useful figure, since it is largely composed of pass-through logistics costs. Instead, we look at Meesho’s contribution profit as equivalent to ‘net revenues.’ On that basis, the net take rate peaked at ~5.5-6% before dipping down to ~4% in H2 FY25/H1 FY26.

Note: Per the DRHP, a large driver for the contribution margin dip in H1 FY26 was “transitional” increases in logistics cost, which Meesho chose not to pass on to sellers because they felt these were temporary issues caused by the rapid scale-up of Valmo: “To meet strong demand growth, we onboarded short-term capacity at relatively higher unit costs. This strategic decision enabled us to sustain adequate service levels during a period of rapid expansion. Since these costs are transitional in nature, fulfilment fees charged to sellers were not revised. As the network stabilises and temporary arrangements phase out, contribution margins are expected to normalise in subsequent periods.” Concretely, Meesho chose to reduce logistics revenue per order by ₹6.5 from H2 FY25 to H1 FY26, but logistics cost per order unexpectedly only came down by ₹5, compressing contribution profit per order. We can surmise that they expected slightly more logistics cost improvements in H1 than Valmo was able to deliver. This could be viewed as an early signal that Valmo is hitting constraints or just a small speedbump. We’ll watch how this unfolds carefully over the next year.

Below is the bridge from contribution profit to EBITDA:

First, on sales & marketing, note that Meesho was able to cut their marketing spend in half from FY23 to FY24 once the battle with Shopsy and Shopee was over, while still modestly adding net new users. They then grew spend in FY25 and again into FY26, driving significant growth in net new users. Along the way, customer acquisition costs (CAC) have been stable. This is very impressive; very few businesses can double marketing spend YoY without much of an impact on CAC. It suggests that the well of customers Meesho is drawing from is deep and that their marketing is efficient.

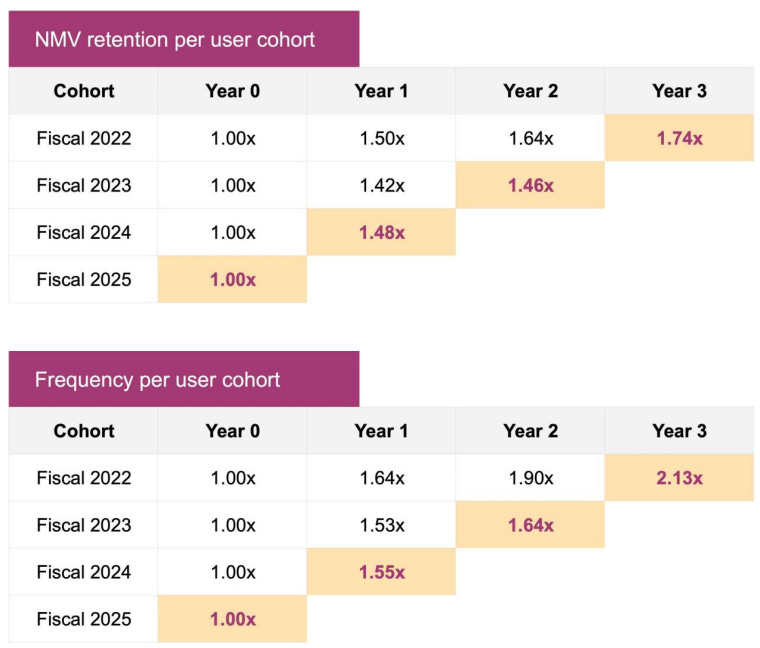

One simple heuristic to measure marketing efficiency is to think about how much contribution profit Meesho is adding annually relative to how much is being spent on customer acquisition. Meesho is spending ~₹150-₹200 to acquire customers and the average transacting user spends ~₹1,600 annually on the platform. At ~8% long-term estimated contribution margin, Meesho is earning ₹120 annually from the average user. New users probably spend a bit less than that ₹1,600 figure, but this triangulates to ~15-18 month paybacks on new user acquisition. This is quite attractive given Meesho’s cohorts are highly retentive and spend more on the platform each passing year.

Second, on employee and other fixed expenses, Meesho has exhibited remarkable discipline before again embarking on an investment cycle in FY26. These costs declined on an absolute basis from FY23 to FY25. In FY26 though, fixed costs have stepped up substantially (~50% YoY excluding share-based compensation), commensurate with the push for accelerated growth.

Net of all that is a business that is still loss making at the EBITDA line—Meesho lost ~₹500 crs in FY24, ~₹580 crs in FY25 (₹3.5 per order), and is on track to lose ~₹1,200+ crs in FY26—but growing very quickly.

Is there a tradeoff between Growth v. Profitability? What about the Long-Term Margins?

Stepping back, Meesho has taken an aggressive, growth-first posture across their P&L in H1 FY26. They chose to pass logistics savings onto the marketplace ahead of Valmo fully delivering those expected efficiencies. They are on track to double their sales & marketing spend versus FY25. They are also growing their engineering headcount and making investments in AI. As a result of all of that, EBITDA losses will likely double in FY26 versus FY25. Those investments have led to the business meaningfully accelerating from ~30% NMV growth to ~45%; that type of acceleration is very rare at Meesho’s scale. This is a bold move going into the IPO and likely has caused some friction (Meesho’s IPO valuation has come down versus expectations a few months ago).

Why did the founders and board take this posture?