A Spotlight on...Urban Company

Dissecting the upcoming public listing of one of Indian tech's greatest success stories

Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 154 new subscribers who’ve joined Tigerfeathers since our last piece.

An especially warm welcome to our new subscribers from the Sri Lankan hospitality sector - මිතුරනි, ඔබ මෙහි සිටීම අපි අගය කරමු. Next Arrack’s on us🍹

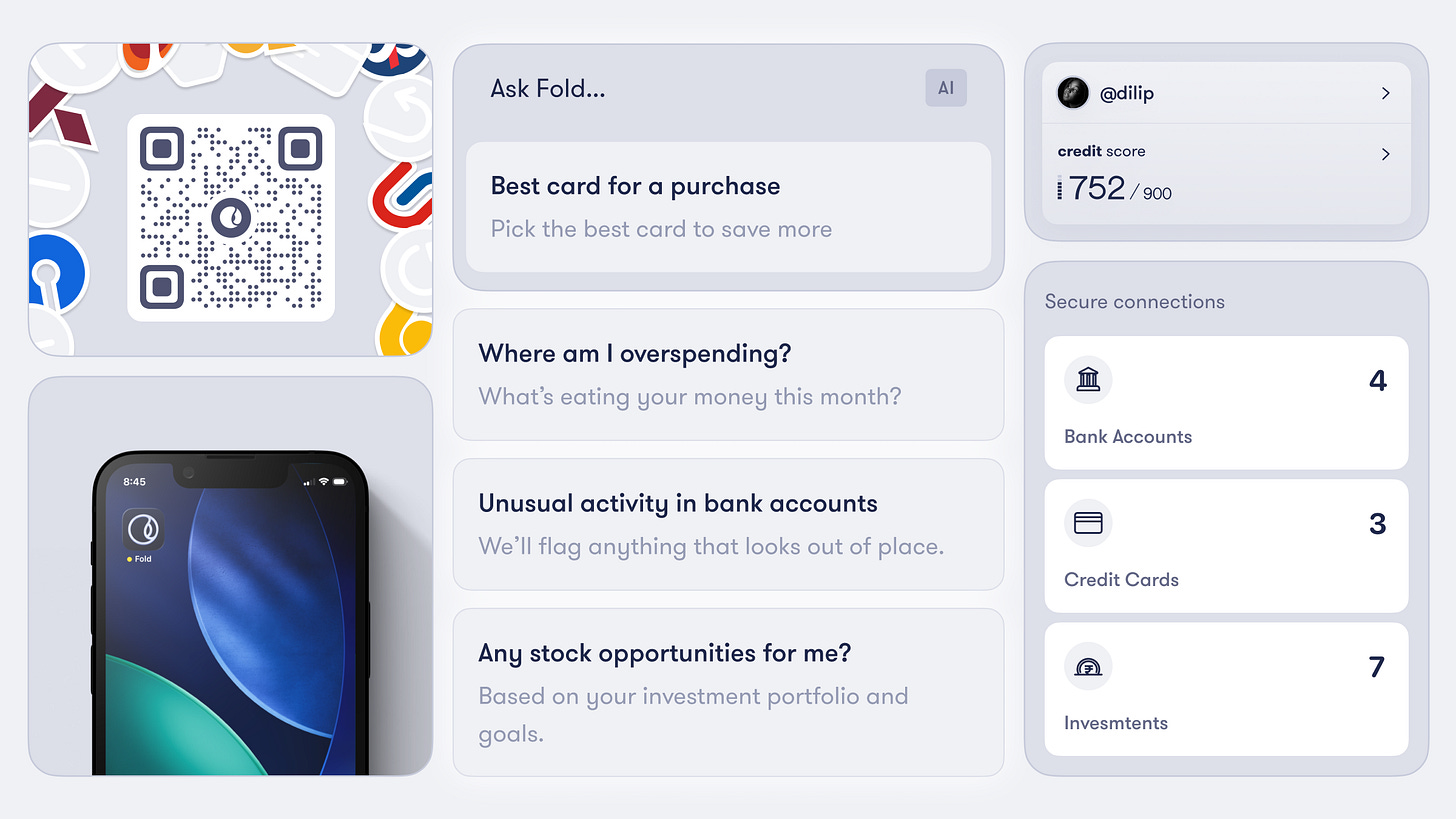

The edition of Tigerfeathers is presented by…Fold.Money

Already loved by 100,000+ users and backed by early believers in India’s fintech story, Fold is reimagining the personal finance experience for young Indians.

It leverages India’s groundbreaking Account Aggregator framework to offer you a single super-powered interface to manage your money (ideal for anyone looking to be “painfully aware” of the state of their finances 🥲).

By seamlessly connecting disparate financial instruments and eliminating siloed data, Fold lets people interact with all their financial information in one place, brought to life with the magic of AI.

The company’s goal is to shuttle a generation held back by outdated tools and archaic banking software into the future of money, making personal finance easy and delightful, and financial decisions more informed and airtight.

As India’s digital public infrastructure scales and AI becomes a more prevalent part of our routines, Fold envisions a future where finances aren’t just visible, but self-driving.

If you’re keen to learn more about why they do what they do, browse through their manifesto here, or dive into the Fold universe using the link below:

And if you're interested in sponsoring a future edition of Tigerfeathers, hit us up on Twitter/LinkedIn or by replying to this email. With that, let’s get to it.

Friends, if you were around in December 2024 when we did our usual year-end wrap up, you might remember us talking about how we'd thus far done a terrible job of turning the spotlight away from ourselves and towards the incredible community that reads this newsletter.

The best part about Tigerfeathers has always been the people who read it. Every week we're blown away by the quality of subscribers who join, read, and share our work. And among that group are some of the sharpest writers and thinkers from the Indian tech and business ecosystem. It felt a little silly for us not to start sharing the microphone with you.

So, as part of our quest to turn this newsletter into the home of the most thoughtful writing, storytelling, and analysis from the Subcontinent, last year we announced The Tigerfeathers Spotlight Series - our attempt to feature the best guest writing from and on India. Our hope was that this would arouse the interest of anyone that either loves to write, wants to write, or that uses writing as a key part of their day job - to draft investment theses, scientific research, funding memos, long form essays, investigative journalism, original fiction etc. At the most basic level, the goal is to celebrate the written word and its practitioners, and learn alongside some really talented people.

Plus, as the Reel economy erodes more of our braincells day by day, this will likely be the last bastion on the Indian internet for anyone looking to preserve any shred of their attention spans. If we can pair people that have something to say with people that enjoy investing the time to read and learn new things, we’ll consider it mission accomplished.

With that being said, after six months of parsing through some awesome applications (and saying ‘no’ to people we have no business saying ‘no’ to), we’re excited to share that our first four contributors are ready for the podium. They couldn’t be more different in terms of what they do, and each of their four pieces couldn’t be more different in terms of format, style, and content. We hope you will appreciate their efforts as much as we do. The idea is to space these out over the next couple of months, starting with this week…

Into The Spotlight

First up, we’re going to hear from Paavan Gami.

Paavan is the founder and managing partner of Raas Partners, a US-based investment firm predicated on taking a concentrated, long-term approach to investing in Indian public equities. Before starting Raas, he cut his teeth at McKinsey, SPO Partners, and the storied Greenoaks Capital, where he worked alongside investing wunderkind Neil Mehta in search of companies that offer JDCEs (“Jaw-Dropping Customer Experiences”, not Jittery Dolphin Circus Exhibits, in case you were wondering).

Raas isn't looking for hot stock tips or to ride seasonal or sectoral rotations. Instead, they're obsessed with what Paavan calls “Inevitables” — businesses with such strong competitive moats and exceptional founders that their long-term dominance feels, well, inevitable. Think of it as venture capital thinking applied to public markets: at the simplest level, they're betting on founder-led companies that are still early enough in their journeys and have “strongform rights to win” in massive, fragmented Indian markets. Their intention is to hold a handful of these ‘Inevitable’ companies for years rather than owning dozens of good-not-great candidates, aiming to build “a firm with venture-like compounding advantages”.

He borrows the terminology from Warren Buffett’s 1997 shareholder letter, where Buffett writes that: “Companies such as Coca-Cola and Gillette might well be labeled “The Inevitables”… no sensible observer - not even these companies’ most vigorous competitors - questions that Coke and Gillette will dominate their fields worldwide for an investment lifetime. Indeed, their dominance will probably strengthen … Charlie and I can identify only a few Inevitables, even after a lifetime of looking for them.”

When it comes to searching for Inevitables in India, Paavan's thesis is that the country’s supply-side constraints create longer periods of supernormal profits than you'd see elsewhere. Poor infrastructure, red tape, and capital scarcity mean that when a great business gets established, competitors are slower to emerge, thereby giving incumbents an extended runway to compound their advantages. It’s why India’s public markets exhibit such a potent Power Law when it comes to sectoral leadership. From his POV, India has the opposite of China's hyper-competitive dynamics, where fast followers can quickly erode early leads.

What buttresses Raas Partners’ work is the observation that in India most high-growth companies go public much earlier than they would in the US, meaning you can theoretically invest in tomorrow's category winners at today's prices if you know what you’re looking for. Added to this is Paavan’s belief that the country’s economy is still relatively nascent and unorganised, meaning there is plenty of runway to grow at the macro and micro level, making India “one of the world’s best hunting grounds for exceptional long-term public market investments”. Eschewing the typical quarterly financial beats, Raas aims to build conviction on where their potential ‘portfolio companies’ will be in 2030.

Given the incredible depth and thoughtfulness of Raas’ past company analyses (which Paavan has shared with us), we were keen to offer him a stage to do his thing for our readers. So, for his Tigerfeathers debut, Paavan offered to do an open analysis of one of India’s most visible startup successes, one that’s headed for its much anticipated public listing in the coming weeks.

Intro to Urban Company

If you’ve spent enough time in the corridors of India’s tech ecosystem over the last decade, you will have at some point encountered a common remark about one of its most vaunted consumer-tech leaders:

“Urban Company has no global comp”

Back in 2013, when Abhiraj Bhal, Varun Khaitan, and Raghav Chandra returned to India after their respective innings working in the US, they would plant the seeds for the emergence of a uniquely Indian business—one that stands today as both prideful ambassador and early proof of concept for India's mobile-first economy. What started as three friends trying to solve the simple problem of finding a reliable plumber in Gurgaon has evolved into something genuinely unprecedented in the world of on-demand services.

While brainstorming over the potential requirements of an Indian populace that was moving to its largest cities in droves, Abhiraj, Varun and Raghav noticed a glaring disconnect: while the process of ordering products online had become seamless, the process of booking services remained a nightmare of unreliable contractors, opaque pricing, and unprofessional behaviour. Their solution wasn't just another marketplace, it was a complete reimagining of how service delivery could work. Unlike typical lead-generation platforms that simply connected customers with service providers, Urban Company (originally UrbanClap) took full responsibility for the entire experience - training professionals, standardising pricing, and guaranteeing quality.

Today, they stand as a category-defining company with a unique product that solves several of the most pressing problems faced by service customers and service providers; a true model of how marketplaces can creatively align the incentives of their key stakeholders.

What makes Urban Company special isn't just its technology, it's the company's obsessive focus on transforming the lives of service professionals themselves. Rather than treating gig workers as expendable labour, Urban Company has created what amounts to a massive upskilling and wealth creation engine. The company operates over 220 training centres across 15 cities, employs 200+ full-time trainers, and has issued stock options to hundreds of service professionals through an evergreen fund. According to the founders’ assessments, service professionals on their platform earn 50-100% more than offline alternatives, with average monthly earnings jumping from ₹10-15k to ~₹27k, to say nothing of the other benefits (like health and life insurance, or vehicle and home loans) that the company facilitates for its constituents.

The numbers tell a story of both scale and impact. Urban Company reported an operating revenue of ₹1,144 crore in FY25 with a profit before tax of ₹28.5 crore—their first profitable year after a decade of operations. They’re at a fascinating juncture today, having made meaningful forays into other geographies and categories (namely, products like water purifiers and door locks).

But also notable is the human infrastructure they've built: ~48,000+ monthly active service professionals serving customers across 22 cities, catering to 6.8 million annual transacting users. Perhaps more than a tech story, it's a case study in how thoughtful business building can create genuine socioeconomic mobility at scale, turning what was once an entirely informal sector into a structured pathway to middle-class earnings and dignity of labour.

If you were simply judging the performance of Urban Company by Richard Branson’s maxim that “A business is simply an idea to make other people's lives better”, this would be a different kind of essay (and definitely more nuanced than the salutations in the paragraphs above would suggest). But for the purposes of today’s piece, to arrive at a more objective conclusion, Paavan has elected to dive much deeper into the guts of Urban Company’s business to formulate his own picture of their future. That’s what’s in store for you today.

What you’ll get from reading this

Finally, it’s probably important here to set expectations about what this piece is and what it isn’t.

This is not the story of Urban Company. For that, two good starting points we recommend are this conversation between Varun Khaitan and Raghav Chandra with Shantanu Deshpande on The Barbershop, and this conversation featuring Abhiraj Bhal on Accel’s Seed To Scale podcast.

This is also not a commentary on Urban Company’s transformative impact on urban India, or its legacy as an engine of socioeconomic mobility for Indian service professionals. It’s also not a buy/sell recommendation 😅. Rather, this is a dissection of Urban Company’s numbers, performance, and future prospects from the perspective of someone whose day job it is to take a dispassionate and long term lens to public markets in India, specifically in search of companies that fit within his fund’s ‘Inevitability’ framework.

Paavan’s analysis largely draws from the information disclosed in Urban Company’s recently published draft red herring prospectus (DRHP) and annual report for 2024-25. Needless to say, nothing in the paragraphs below should be construed as financial advice. If you’re looking for get rich quick tips then look out for the brochure of our Labubu Life Savings Retirement Fund when it drops later this year (no but seriously, none of this is financial advice, pls do your own research).

Lastly, this is not a typical Tigerfeathers piece. You can expect some Tigerfeathers-ish ornamentation through the course of Paavan’s analysis just to lighten things up, but the words you’ll read are his. The idea with this series is to learn from people within this community - how they think, how they write, and what they’re working on. Our job is to support them in whatever way they need to create something great, whether that’s with a bit of editing, contributing a meme here and there, sending them snacks if they’re working late - whatever it takes. We hope you will lend them the same patience and appreciation you do for us.

With that said, lets get on with it.

🐯 🪶: Before we cede the floor to Paavan, you should know that we will be interjecting throughout this piece now and then to insert memes and commentary. When you see the Tigerfeathers emojis in a block quote, you’ll know it’s us writing. The other way you will know it’s us is because the intellectual quality of the writing will drop off significantly when we take over.

Lastly, since the words you’re about to read are going to come from a new face, we want to just give you a glimpse of what that face actually looks like.

So, what does Urban Company do?

Say you have guests visiting you tonight. It’s summer, it’s hot, and the AC suddenly breaks down. What do you do?

Or, say you’ve decided to renovate your home with a new paint job. Or you’ve moved cities and are looking for some part-time help with cooking and cleaning. Maybe you want someone to occasionally check in on your aging parents and help them with basic exercises.

All of these consumer needs, ranging from ‘hair on fire’ problems like an A/C repair job to ‘recurring’ requirements like a weekly cleaner, fall under the motley, Frankenstein category of “home services”. Urban Company connects customers who need these services with the service providers (SPs) who offer them.

Why does that matter?

Because all the scenarios we just highlighted represent a problem that most city-dwelling consumers face.

The solution lies in asking around for referrals, playing phone tag with service providers, getting quotes from different vendors, scheduling an appointment, praying that the person you’ve chosen shows up at the agreed-upon time, and hoping that they aren’t overcharging you and they’re good at what they do.

These categories also have one other thing in common: they’ve historically been undigitized and unorganized; not just in India, but all over the world.

Home services has been one of the ‘white whale’ consumer TAMs and, just like the fictional Moby Dick, has lured many well-funded ambitious startups into murky waters.

Most of the companies that have forayed into this segment have burned money and closed down. Even the ones that survived have seldom set the world alight.

For example, San Francisco-based Thumbtack raised almost $900m to make the home services experience as ‘click-of-a-button’ simple as the food delivery or ride share experience, but they’ve struggled to reach escape velocity. While they admirably (and profitably) generated ~$400m of revenue in 2024, their scale pales in comparison to their more successful local commerce cousins like Doordash and Uber.

Remarkably, the most successful home services company in the world might have been born right here in India. Urban Company will be the first tech startup in this entire segment (from anywhere in the world!) to go public.

They’ve scaled to $130m in annual revenues in an economy 1/8th the size of the US, so GDP-adjusted, they’re twice as large as Thumbtack is.

To get there, Urban Company has taken on the difficult task of offering a ‘full stack’ customer experience. They control everything from service professional training to the products that are used to the t-shirts that are worn, all of which delivers a consistency of service that is not available anywhere in the world. This is not your mother’s asset-light marketplace!

Today, dear reader, we will unpack Urban Company’s story, analyze their prospects ahead of the IPO (very much not investment advice!), think through some of the scaling challenges they may face, and discuss how the arrival of “quick everything” may shake things up.

Wait a second, how big is this market exactly?

The Urban Company stock exchange filings claim that home services constitute a ~₹500,000 crore ($58 billion dollar) market, composed of many heterogeneous services.

Home cleaning, senior and baby care, appliance repair, home renovation/painting, and cooking are each ~$5-$10B home services sub-categories in India.

That’s… chunky. Who is spending that money?

Let’s attempt to answer this question by analyzing the largest and most familiar slice of the home services pie: home cleaning.

Today, there are about five million full- and part-time domestic workers in India, per employment survey data. Each of them earns ~Rs. 1.5-2 lakhs annually.

Around four million of these folks work in cities, and each of them services two households on average. This implies that some eight million urban households avail of domestic help.

Given that there are estimated to be some ~80M urban households in India, we can infer that the home service of cleaning is something that only the top 10% of households actually pay for.

In other words, we can reasonably assume that only the top decile of households can afford to have someone external to the household help them with a chore.

As India gets wealthier and families nuclearize, home services adoption will spread. UC’s DRHP estimates the market-level growth rates to be ~10-11% annually. Today, however, Urban Company is selling a discretionary, luxury service to households concentrated in India’s 8 metros.

🐯🪶: Fun fact: DRHP stands for Draft Red Herring Prospectus, which is a strangely-named information document submitted to the stock exchange before a public listing. But it also sounds like it could be the worst spell in the Harry Potter universe.

That makes sense. So how did Urban Company start?

Founders Abhiraj Bhal and Varun Khaitan were batchmates at IIT Kanpur (class of 2009) and then both worked at BCG (albeit in different offices) before deciding to start a business together.

In 2013, they moved back to Delhi and started brainstorming startup ideas. During that time, they met third co-founder Raghav Chandra, who had been a software engineer at Twitter before starting a venture of his own.

Together, they spent months interviewing users about pain points in their daily lives. One consistent refrain came up – home services. Attracted by the sheer size of the prize, they decided to go for it in late 2014. Urban Company was born.

Incidentally, 2014 was something of a bumper year for hyperlocal commerce, not just in India, but globally: it was the year that marked the beginning of the modern food delivery model.

While restaurant listing models had existed before, Doordash, Postmates, Deliveroo, Meituan, and Swiggy all came into existence in 2014 to build the “logistics enabled” model in which the platform actually took the responsibility to deliver the food to the customer’s door and thus ensure its freshness.

It was against this backdrop that the UC founders got going. However, they weren’t the only ones to notice the opportunity.

A number of other Indian startups — LocalOye, GoodService, Zimmber, Timesaverz, Mr. Right — were also founded that year to go after home services. So competition was fierce, especially when you consider that horizontal classifieds platforms like Quikr and OLX also had their eyes on the home services prize.

So if there were so many players in this space, how come only one emerged?

Warren Buffett has a famous quote:

When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.

Home services had long been one of those iconic iceberg markets where even brilliant teams ran into trouble.

Why though?

Good question. To answer that, let’s break down the hidden dynamics of labour marketplaces.

What customers would ideally want is pretty clear in theory: an app or website where they can see a list of vetted nearby SPs, browse a ‘menu’ of prices for various services, and book an appointment with an SP in a reasonable time frame.

Yet delivering this experience consistently at scale to actually tap into that demand has been hard for the following reasons:

Service professional adverse selection: many of the very best SPs are already busy. Home services professions require on-the-job training and experience, so SPs usually get their start by apprenticing at a local small business (like a salon or a garage). The very best folks likely get promoted and stay in those arrangements. Thus, structurally, the supply available to a new marketplace is going to tilt towards underutilized folks who are newer to the industry, or don’t have a personal brand or book of business that keeps them occupied.

The ‘human element’ results in a poor customer experience: When a customer reaches out to an SP, they expect a response back soon (they are opening up the app to solve a potentially urgent problem!). Unlike Uber drivers, SPs are not near their phone at all times and tend not to be very tech savvy. Hence, their default is to respond to inquiries hours later. This isn’t just a bad customer experience; it’s very bad for the platform’s business. Slow SP response rates result in a lot of lost sales (in those intervening hours, the customer will have called five other SPs they found online). Similarly, “no shows” are another big problem. Sometimes, this is driven by SP negligence, but there are also many structural drivers of delays: the SP’s previous appointment could have been more complicated than expected, they could have simply hit traffic, or they could have taken a different job off-platform (which is higher margin for them) and forgotten to update their calendars.

🐯🪶: One follow up point is that today’s consumers have negative attention spans. If they can’t speak to or finalize a booking with an SP immediately, they just switch the tab to YouTube and search for Japanese cooking content in a disgruntled rage. Or maybe that’s just us.

A still from one of our favourite cooking channels ever - Cooking With Dog. Watching the grey poodle Francis enjoy the aromas of the flavourful food as classical music plays in the background is a guaranteed stress buster. And no, despite the ambiguous phrasing of the channel’s name, dog is fortunately not the main ingredient in the dishes made on this show. Source. Pricing opacity: Customers want to pay a fair (or less than fair…) price, but they’re not experts at assessing what “fair” is. Toilets don’t break so often that we know how much they should cost to fix! Given the information asymmetry, customers always feel that they are getting ripped off. Moreover, because the services rendered are highly bespoke by nature (how much a paint job will cost depends on the room’s size, its height, and how many coats are needed to cover the previous paint job), providing accurate quotations online before an appointment is difficult. Hence, the customer often ends up getting an approximate quotation in-app and then is cited a higher price once the SP arrives and surveys the scene. Customers obviously hate paying more than they expected.

🐯🪶: *Hopefully* your toilet doesn’t break so often that you know exactly how much it will cost to fix. It would be soul-crushing for your plumber if you called him and said ‘Yeah Santosh, I got a grade-4 blockage again. Looks like it’ll be around 2.69K in damages. Bring a gas mask’.

Service professional disintermediation: when the SP meets the customer in person, it’s quite easy for them to say “pay me in cash off of the platform and we’ll both save some money!” or “these are my WhatsApp details for the next time you have this kind of problem.” This kneecaps the “LTV” (lifetime value) the platform was hoping to capture. Disintermediation makes the unit economics of services marketplaces challenging, and tough unit economics, in turn, mean less budget with which to build brand awareness and really create the category. [NB: Urban Company’s approach to tackling this problem is not to dissuade their SPs from ‘offboarding’, but to provide both customers and SPs with enough reasons to continue using their platform as the preferred way to transact eg: incentives for upskilling and development, insurance, warranty, safety etc]

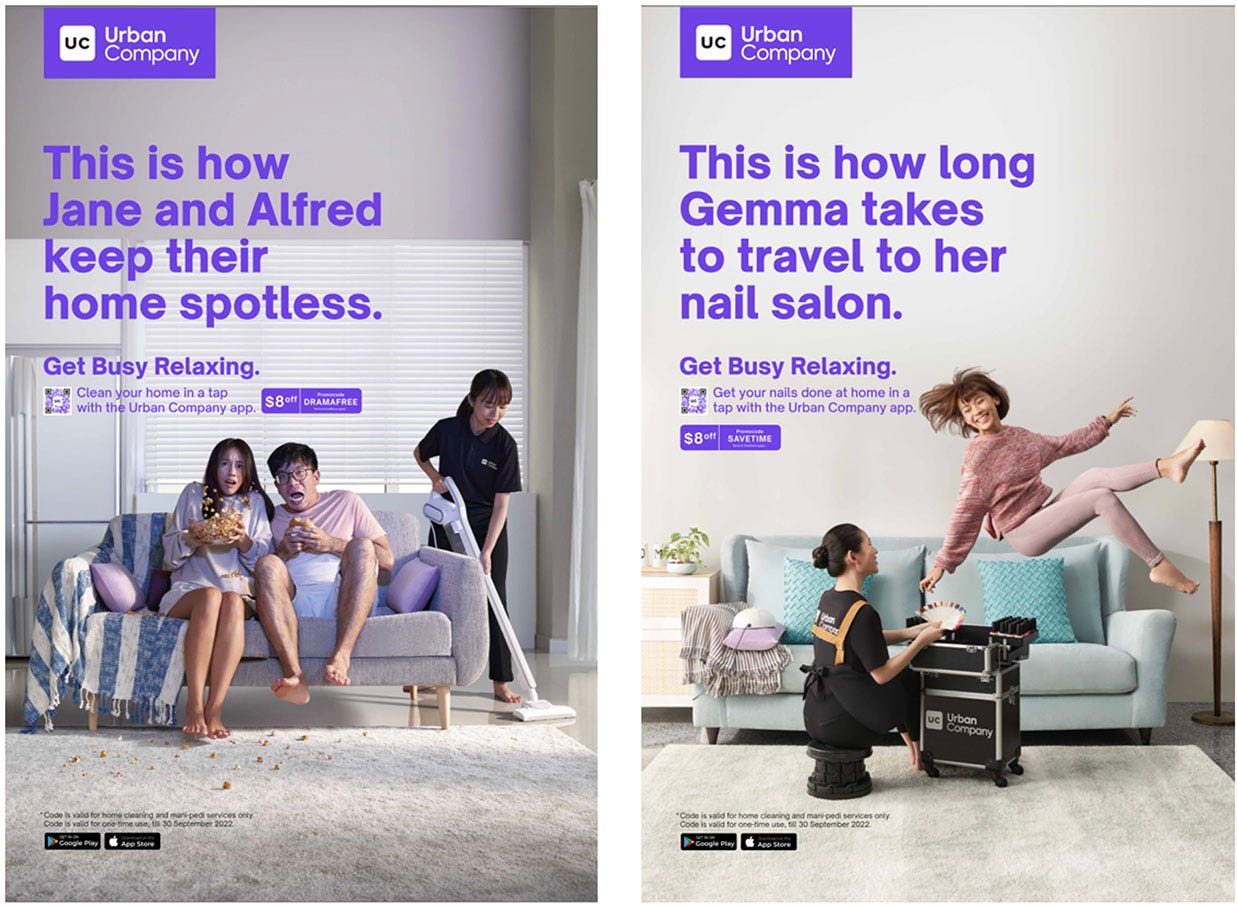

Low frequency makes customer acquisition challenging: Many home services user needs are triggered by an exogenous event – the A/C breaking or the homeowner deciding to do some renovations – and these are infrequent enough that performance marketing doesn’t work well. 99% of customers seeing an Instagram ad for “A/C repair” won’t have a broken A/C! Instead, home services platforms have to rely on brand marketing; the goal is to build top of mind awareness as a place to go for all home service needs, so that when something crops up down the road, the customer remembers the platform. At scale, this can be very powerful, but in the early days, this can be very painful and costly.

Two sided marketplace balancing act: All of these things together make it hard to scale a two-sided marketplace in home services. To top it all off, the platform constantly needs to maintain a careful balancing act. If they acquire too many users relative to SPs, the users will not see availability or will be offered appointments weeks away, which is a bad experience and will result in churn. If they acquire too many SPs relative to users, the average SP will only get a little business from the platform, so they will not be incentivized to behave well (e.g. replying promptly to inbound customer requests). This balancing act needs to be managed at the micro market level (neighbourhood), which makes it even tougher!

These are problems that mar labor marketplaces all over the world. India presents its own additional challenges: there are a lot of folks that are ready to work, but many do not understand customer expectations around how to communicate, how to look presentable, and so on. The customer’s bar is even higher than normal in home services because the SP is actually entering the house.

There are also trust issues: “How do I know I’m getting someone experienced? How do I know the products they’re using on my floors (or in my hair) are high quality? How do I know the person I’ve booked will show up on time? How do I know I’ll be safe?”

To create a really big business in home services, you need to navigate all of these obstacles!

That… doesn’t sound easy. So how did Urban Company solve these problems?

What made UC different was how they approached the problem: they were comfortable rolling up their sleeves and getting very operationally involved. In doing so, they were able to deliver a meaningfully better customer experience. They operated two different business models in parallel:

The “matchmaking” model (for heterogenous categories like interior design and larger scale renovation projects): UC’s matchmaking model was an evolved version of the erstwhile listings/classifieds model. Users select a service category on the app (e.g., yoga teacher, plumber) and answer a series of questions about what they are looking for. UC’s algorithm then recommends a handful of suitable SPs who connect with the customer and offer a quote. Each SP has to pass background and quality checks before being listed (only 20-25% are accepted). UC charges SPs a commission for each customer they speak with and collates reviews and feedback to aid future customers in making a good decision. Low-rated providers are removed from the platform. This model works in categories when the “job to be done” involves a dialogue between customer and SP.

🐯🪶: Not this kind of matchmaking.

2. Urban Company’s homegrown “full stack” fulfilment model (for standardized categories like A/C repairs, cleaning, and pedicures): This model was even more novel. Under the full stack model, Urban Company actually takes on ownership of the customer experience end-to-end. This is doable in categories where the “job to be done” was quite discrete.

For the latter model, which ended up becoming their dominant model, Urban Company analyzed each relevant category and broke it down into “standard service units” (SSUs).

Similar to a unique SKU available at a retail store, each Urban Company SSU is a discrete task with “defined service parameters, standard operating procedures (SOPs), price and in several cases, prescribed products for use during their service delivery.” For example, a sixty-minute massage is one SSU, a 30-minute beard trim is another, and a water purifier filter change is yet another. The SOP for a beard trim is as detailed as to include a five-minute head massage, using a particular type of beard oil, and bringing a particular vacuum to clean up the hair.

There are also overarching SOPs, including timeliness, how to greet a customer, how to recommend other services to the customer, and so on. This includes policies like wearing an Urban Company t-shirt when visiting customers. UC also asks SPs to upload photos of each job after it’s done, which can then be audited for quality assurance purposes. The goal is for the customer to feel that the experience is being delivered by an Urban Company employee, not a gig worker.

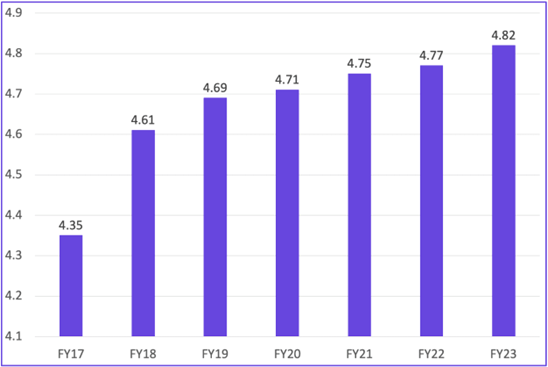

UC originally recruited SPs by approaching employees of local salons and repair shops and convincing them that UC would offer higher wages and more flexibility. Over time, they have shifted to instead recruit freshers, who they train from scratch in the “UC way” [NB: they also maintain extremely strict quality standards for SPs. Eg: historically if a SPs user rating fell below 4.7/5, or if they cancelled 5 bookings in a month, they were kicked off the platform].

In either case, an SP must enrol in UC’s training course and pass a certification before they can start. Accordingly, UC operates their own training centers (>200 of them, all across India) where they teach SPs how to deliver on each SSU they’ve designed. This training is non-trivial. It costs ~₹60,000 on average. SPs pay for half of this cost (otherwise they would not be incentivized to make the most of it), but Urban Company provides working capital loans to make this upfront outlay affordable. After classroom training, there is a period of in-the-field training alongside a more senior SP.

In contrast to the marketplace model wherein each SP sets their own prices and haggles with the customer, UC sets the prices for each SSU, takes payment from the customer, and then remits ~70% of the price to the SP and keeps the remaining ~30% as their commission.

SP calendars are also managed by UC. SPs can choose which shifts they work, but within those shifts, UC has flexibility to schedule appointments on the SP’s behalf. This enables UC to offer “instant booking” options for customers.

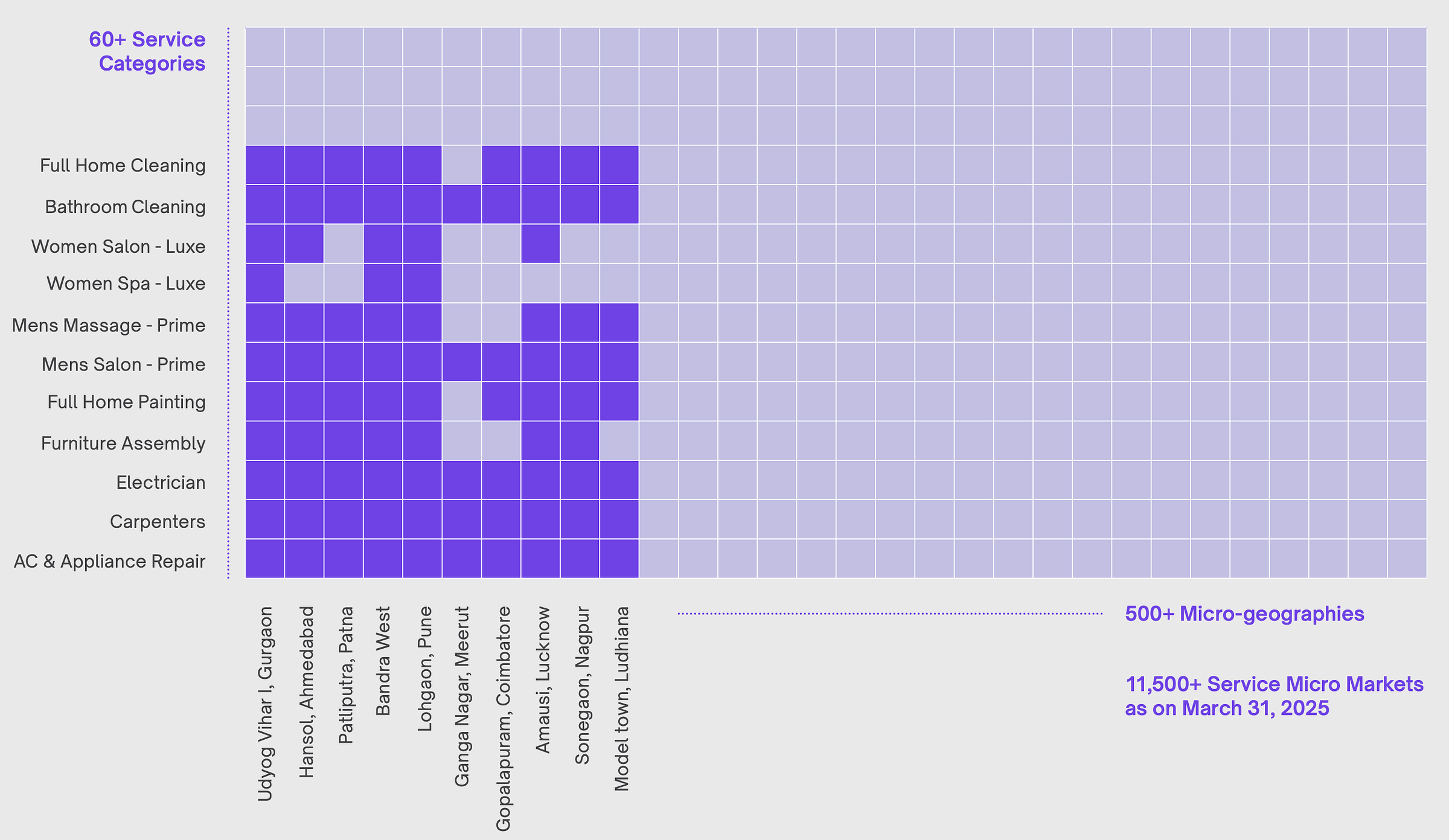

Below is how the SSU model is operationalized internally. Each micro market has a set of SSUs on offer. When they enter a new micromarket, they’ll start with the basics (cleaning, A/C repair). As the UC brand grows locally and the base of acquired customers expands, they then introduce new services.

The full stack model is a dramatically different approach than the ‘hands off’ classifieds model, which merely connected customers and SPs but could not solve the trust deficit in the transaction. It’s much harder to scale, which we’ll come back to, but it delivers a win-win for all stakeholders:

Customers get great reliable service, which manifests in strong NPS (net promoter score: a measure of how likely the customer is to recommend the service to others), and high repeat and referral rates.

UC solves many of the business model issues we discussed earlier. Rather than depending on existing SPs, UC is able to hire freshers, train them up to the UC standard, and also demand more of them (with regard to how they deliver the service). They can also offer price transparency and instant booking to customers, which improves conversion rates.

SPs also get a much better employment experience. Post the training, they are earning a healthy ~₹300 per hour (after all expenses, including the commission paid to UC and transportation costs), almost 2x the median wage of a gig worker in India. They also get health and life insurance paid for and a sense of community, while maintaining the flexibility to work on the days they choose to work. UC calls them “micro entrepreneurs” or “micro franchisees” rather than “gig workers”, and SP empowerment does seem to be a real part of UC’s cultural ethos (just browse through their Youtube channel for some feel-y feels).

As alluded to previously, UC scaled both models - matchmaking and full-stack - for a few years but ultimately chose to focus on the full stack model exclusively by 2018/2019. In doing so, they exited some long tail categories that were served by the match making model (e.g. wedding planners, photographers). The impact of this pivot is clear in their NPS data:

Note: The ‘full stack’ approach is powerful in low trust, high quality-variability categories. Spinny is the other startup in India that has used it to good effect. Spinny’s full stack marketplace actually buys used cars from customers, refurbishes them, and then sells them onward (versus prior classifieds models that merely connected buyers and sellers but could not solve the trust deficit in the transaction). Arguably, grocery quick commerce is also built on the same insight; rather than picking from stores and delivering them (JioMart’s original model), run the stores yourself! Solving hard problems and delivering a better customer experience as a result is a sure shot way to build a great business.

And what about Urban Company’s more recent growth initiatives?

By 2020, going into COVID, Urban Company had a few flagship categories: beauty & wellness (salon services, haircuts, messages), home services (cleaning, pest control), and repairs (appliance repair, plumbing). They were doing ~250Cr of revenue in FY20.

COVID was difficult for them as it was for all businesses in India, but they rebounded strongly by the second half of FY21 and revenues doubled year-over-year from FY21 to FY22. This was led by the beauty category; salons themselves were shut and so UC’s at-home services became very sought after.

In mid-2021, UC raised a monster $255m funding round and was valued at $2.1bn post. They then orchestrated a secondary sale in Dec 2021 to give employees liquidity that valued the company at $2.8b post.

With that capital, they entered a number of new geographies. Within India, they expanded into Tier 2 towns, going from a presence in just the metros to ~50 cities. Largely, this has not worked out given lower propensity to spend; the vast majority of the Indian business still comes from the metros.

They also experimented with international expansion. Their ventures in the US, Australia, and Saudi Arabia were short-lived, but they’ve seen success in Dubai and Singapore. Both of those are markets with high Gini coefficients and high density, so it’s not surprising that those are the kinds of cities that did work. High income inequality is often an enabler of gig economy businesses like UC, since there are lots of people who want to work and also lots of people who can afford to pay for convenience.

🐯🪶: The Gini coefficient is a statistical measure of inequality in a population; the higher the number, the higher the inequality. It is absolutely not a metric used by Aladdin’s offspring to compare the relative quality of their magical servants.

The other expansion vector they focused on has been getting deeper into certain categories. In particular, they’ve built their own consumer electronics brand called Native, under which they currently offer a smart door lock and a smart water purifier (both of which can be controlled within the Urban Company app, which increases engagement). Rather than SPs installing a third party product or supplying third party water filters, they now can supply UC’s own product, which expands the platform’s contribution margin.

Native is likely just the first step here; UC’s larger aim is to go after the broader appliance spare parts market. When an A/C repair person procures a spare part for you, he is very likely including a healthy 30-40% mark up on that spare part and that’s a big additional income driver for him. There’s even more margin sitting at the spare part retailer/distributor layer. UC wants to tap into this profit pool.

Their model today is a bit circuitous. They know their repair SPs are earning more on certain jobs that involve spare parts and thus charge them a higher commission on those jobs. To do this, they’ve gotten down to the specifics of cataloging every spare part, its average selling price, and an estimated SP margin.

While this helps Urban Company calibrate their pricing and commission levels better, the longer-term solution is to get into the spare parts game directly. For something like a water purifier, this is doable. There are just 15-20 parts and consumables that would need to be stocked at a regional UC depot (and this is simplified further now that water purifier sales will mostly be standardized to Native’s hardware).

For air conditioners and more complex appliances, it’s not so simple operationally though. There are many, many more parts and also both OEM and non-OEM variants. Managing that inventory in all of the micro markets UC is in will be tricky. But still, this is a large margin opportunity for them.

Today, Urban Company is on the verge of going public and they’ve filed their DRHP. They reached ~₹1,100 cr of revenue in FY25, growing ~40%. The vast majority of that revenue still comes from their core Indian Marketplace segment, but both the Native and International segment revenues are also growing quickly.

Alright, stop edging us already. Just dive into the Urban Company financials.

The DRHP has a number of great nuggets for us about UC and its future.

First, let’s analyze their core Indian Marketplace segment:

Urban Company Core Services Marketplace Metrics

The core topline metric is Net Transaction Value or NTV. NTV is the total amount paid by the customer to UC (before the payout to the SP). UC’s NTV growth has come down steadily each year, from nearly ~50% growth in FY22 down to ~20% growth in FY24 and FY25.

Clicking into the drivers of that, the first derivative of growth is stagnating. Users are growing their spend on the platform by 5-10% annually. Some of that spend growth is more price-led (e.g. UC raising prices in mature micro markets where they feel the brand is well established), so their frequency-led growth (i.e. the metric that corresponds to successful cross-selling of new services) is quite tepid.

On the user acquisition front, they are acquiring 700k-1M new customers annually but the pace of that growth is not increasing. If they’re unable to re-accelerate user acquisition, marketplace NTV growth will continue to slow. Other metrics show stagnation as well — the total number of micro markets covered has not grown much since FY22 and the number of active services pros has only grown ~10% since FY23.

What’s happened under the hood is that UC had a boom in their beauty business in FY22 and FY23; salons were shut and so customers used UC during that period. Subsequently, customers have gone back to their offline providers (it’s hard to fully replicate the salon experience at home, especially for high end procedures like hydra facials and so on).

🐯🪶: What is a hydra facial? A new Korean beauty trend for multi-headed mythical beasts??

Hence, their beauty business has actually been flat to declining since FY23 and they are trying to replace that growth with the appliance repairs business, with the new Native initiative, etc.

On the contribution margin front, things are healthier. Take rates have expanded only modestly, meaning that for the most part Urban Company continues to share the same percentage of NTV with their SPs. However, it’s important to note here that there was a big step up from a ~26% take rate in FY21 to the ~30-33% range seen more recently, which caused a lot of uproar among SPs and suggests they have limited room to pull that lever any further.

Nonetheless, the contribution margin has shown significant improvement in recent years. Much of that is COVID related costs going away (e.g. providing PPE to SPs). They’ve also made a significant dent in their call center and other related customer support expenses. We think that the optimizations of these costs are mostly also played out at this point.

Finally, there are operating costs such as sales & marketing expenses, payroll expenses, and onboarding and training expenses associated with new service professionals. UC has done a remarkable job managing to keep this line item flat since FY22, which has allowed for very consistent annual operating leverage. Circling back to why customer and SP acquisition has been stagnant, one can surmise that part of the story is that UC has held back on investing in growth ahead of the IPO so as to show this kind of operating leverage.

In FY25, they showed ~3.3% EBITDA margins (as % of NTV) and this could expand to ~5+% margins in FY26 if the same trends hold. This puts UC in the same company as other dominant marketplaces like Zomato’s food delivery business, which has reached the 4-5% EBITDA margin range. Longer term, UC could stabilize in the 6-8% range given their high contribution margins.

🐯🪶: If all the numbers and financial jargon are getting to your head, don’t worry. We’re introducing the Tigerfeathers School For Kids Who Can’t Math Good Or Do Other Things Good Too. Just follow the pretty pictures and everything will be alright.

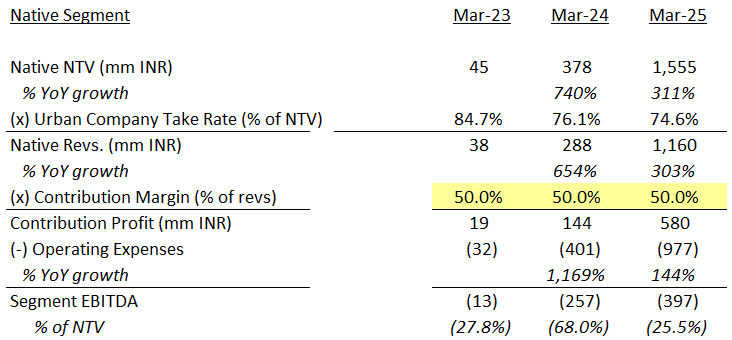

Urban Company Native Hardware Business Metrics

Moving on from the company’s core marketplace business, Urban Company’s new Native business line looks promising as an up-and-coming value driver.

Native is in a nascent, hyper growth stage, growing more than 3x YoY off a small base. The absolute scale is also impressive: Eureka Forbes, the giant in the space (they own the Aquaguard brand), does approximately ~1,000 crs of water purifier revenue, so Native has already reached 1/8th of their scale just two years after launch.

UC doesn’t share much detail on Native’s economics, but note that its take rate is much higher than that of the marketplace business. This makes sense. Native’s NTV includes both the cost of the service and the cost of the hardware, and UC only remits the former to the SP and keeps the latter. Eureka Forbes operates at nearly ~60% hardware gross margins so we have assumed that UC currently operates a touch below that given they are subscale.

At the EBITDA level, this segment is loss making today given the high growth, but we could imagine it potentially touching 10-15% EBITDA margins at a steady state. For context, Eureka Forbes earns 10% EBITDA margins but doesn’t capture much of the high-margin filter replacement business, whereas UC should be able to capture the additional ~5% EBIDTA margin on replacement services in addition to the ~10% they earn from the hardware sale.

Urban Company Overseas Business

Finally, the international segment of Urban Company’s business is more mixed:

This segment comprises three different geographies with different maturity profiles. Singapore and Dubai are cities they have been in for some years. UC entered Saudi Arabia more recently in early FY25 (they had a small presence before but made a bigger push in FY25); the push in KSA has been responsible for some of the re-acceleration in growth rates.

Given higher spend per customer and more of a mix towards recurring cleaning services, UC’s take rates and contribution margins are much higher in these markets. Despite this, they have not gotten to enough scale to leverage their fixed costs to reach profitability yet.

Recently, they’ve taken steps to reduce losses by entering JVs with local operators such as Noon, the large e-commerce player in KSA and UAE. They also announced that the UAE business had reached EBITDA breakeven in FY25, which suggests that the remaining losses are centered in Singapore.

Given the high contribution margins and the opportunity to defray some of the operating expenses by working with JV partners, it seems likely that the international business will also end up being fairly profitable. That said, it will be difficult for this segment to move the needle relative to the Indian business (including Native) given the sheer differences in market size.

So what does this all mean?! Spit it out, Numbers Man!

The UC team has clearly built a great business. They’ve made inroads into a tough market with a high NPS solution. Given the quality of the customer experience and the premium demographic UC is targeting, this should result in attractive pricing power, an ability to bundle premium products like Native, and thus a path to attractive margins.

It helps that there’s essentially zero organized competition, which means they don’t need to worry about competitors bidding on keywords and IPL ads, trying to poach their SPs, etc. They’ll be able to earn their margin in peace!

We would not be surprised if Urban Company ends up one of the most profitable businesses (on a % margin basis) from the Indian internet landscape.

Sounds peachy. Any big challenges we should be aware of?

We think there is one clear challenge they may run into: sustaining their growth. There are already a number of signals that they may be saturating their core market.

The main signal of this saturation is that the company has not grown the rate at which they add new users every year. Although some 700K-1M new users do transact on the platform annually, the number of fresh users added hasn’t recently moved out of that range.

One reason for this is that we know the model has struggled to scale outside of metros. Within metros, there are ~5M households earning >15 lakhs per year (as a reminder, that’s the income sweet spot for UC customers). UC has ~6.5M annual customers, of whom ~80% are from metros, per our estimates. This implies UC has likely already penetrated most of the addressable metro households.

For incremental user growth, they will need to reach into upper middle and even middle income households, but there’s not a lot of evidence that the product-market fit extends to this group. These consumers are going to be more willing to shop around for the lowest cost service provider, even if it means making several phone calls. As a result, we’d guess that the frequency and retention profile of this next set of users is going to be lower than UC’s core cohort of premium households.

We can actually see this dynamic play out in their sales & marketing efficiency. UC discloses how much of NTV comes from newly acquired users and the NTV retention of those cohorts over time. If we compare the cumulative contribution profit generated by each cohort to the sales and marketing investment needed to acquire them, Urban Company is operating at ~2 year paybacks.

This is not impressive relative to best-in-class B2C companies, especially because much of UC’s newly acquired NTV is one-time in nature (e.g. customers using UC for a one-time need and then moving on). What this, combined with the healthy company -wide margins, tells us is that UC’s existing base of customers is very profitable but it’s inefficient for them to spend S&M resources to acquire new users. This makes sense; they've largely captured their core metro audience so growth from here will come from deepening their share of wallet with existing households through cross-sell and premiumization. That will be driven less by sales & marketing and more through innovation (new services like Native, wall panels, and Instahelp).

If those new initiatives are successful, we should see NTV growth, driven by cohort expansion rather than new users, decouple from S&M spend. There are some early signs of this in the recent years, with NTV added expanding despite total S&M spend staying flat-ish. We're hopeful that this will accelerate for UC in the coming years.

That being said, one of our favourite all-time business frameworks is Eugene Wei’s idea of “invisible asymptotes”. Eugene was an early, senior Amazon employee and writes an excellent blog about tech, business, and film (he’s now a film maker primarily).

🐯🪶: Watch out for his new hit thriller. Out this summer in cinemas near you!

The basic idea is that we can decompose a company’s product-market fit into a bunch of micro segments/customer profiles. The product experience as it stands is able to meet the needs of a subset of those segments and what “growth” really means is ramping up towards ~100% penetration within that subset.

In other words, the product experience needs to get better to unlock new user segments and this in turn is what fuels durable growth. For Amazon, there was a large portion of customers who just emotionally, reflexively were unwilling to pay shipping fees; Amazon could only unlock these customers with the launch of Prime ‘free’ shipping.

In Eugene’s words:

“In product there is another form of demand curve, and that is the contour of the customers' demands of your product or service. How comforting it would be if it were flat, but as Bezos noted in his annual letter to shareholders, the arc of customer demands is long, but it bends ever upwards. It's the job of each company, especially its product team, to continue to be in tune with the topology of this "demand curve." I see many companies spend time analyzing funnels and seeing who emerges out the bottom. As a company grows, though, and from the start, it's just as important to look at those who never make it through the funnel, or who jump out of it at the very top. If the product market fit gradient likely differs for each of your current and potential customer segments, understanding how and why is a never-ending job.”

Coming back to Urban Company, we worry that their business is going to hit an invisible asymptote. If we were to analyze their product-market fit by micro segment in the way Eugene suggests, we see the following blockers:

Within the beauty segment, there are commodity services like waxing/threading/male haircuts/massages that can be delivered in an at-home setting in quite a high quality way. These don’t require sophisticated equipment or ambience that can only be provided at a salon and, in fact, by absolving the service professional of the real estate and other overhead costs of the salon, UC can potentially deliver the same quality service to the customer at a lower cost (and greater convenience). However, the higher end salon work (manicures/pedicures, womens’ haircuts, facials, botox) cannot be delivered at home with the same quality. Salons also provide a social experience for women and an opportunity to get out of the house and away from their kids; that too is hard for UC to deliver. The ‘COVID pop’ that UC experienced was some of these micro segments being forced to use UC while their preferred option (going in-person) was not available, but those customers went back to their old behaviors once they could.

Within the “urgent need” segments (repairs and the like), UC’s conversion rates are a function of their hyperlocal liquidity. If an SP is available within two to four hours of a customer’s request, UC will be able to fulfill that job. Otherwise, the customer will move on to another provider. We think the UC operating model is not designed for this kind of service level expectation. Their SPs roam fairly widely in their micro markets and are quite booked up, meaning the chances that there’s an SP near enough to the customer and with calendar availability to show up on a few hours notice is very low. One solution would be for UC to have an SP sitting in each micro market and waiting only for urgent jobs (and charging those customers a commensurate priority fee). However, UC’s flexible, part-time model makes this challenging; they just don’t have enough control over the SPs despite being “full stack”. When they tried to take more control over SP calendars via an “auto accept” feature, there was a huge uproar. In comparison, there’s a small local competitor called Yes Madam in Bangalore that pays their SPs minimum guarantees (basically fixed salaries) and thus has more flexibility to implement such things.

There is also an issue around Average Order Value (AOV). We think UC’s average order values are ₹1,000-₹1,200. This is very expensive for the average Indian household and makes lower stakes, simpler tasks (eg. a quick two hour clean before guests arrive, dishes after guests depart, changing a hard-to-reach lightbulb, assembling furniture) inaccessible for UC’s model. Why are the AOVs so high? Because UC’s micro markets are somewhat sparse, we think SPs are traveling at least 30-60 minutes between each customer’s location. UC needs to amortize this travel time (which has an opportunity cost for an SP who could be working at a salon back-to-back instead) over at least a ~four hour job to make it worth the SP’s time. The informal home services model, where a housekeeper visits several units in an apartment building, is much more efficient in this regard and thus can be delivered at a much lower cost.

There may also be a more overarching issue around the target customer UC is designed for. It’s a premium service, with highly vetted supply, for a premium customer. One learning over the last 2-3 years in Indian e-commerce is that demand is highly heterogenous. Models like Meesho and Rapido that unbundle the bells & whistles that Amazon and Uber put into their services and thus enable value-conscious customers to partake have done really well. While there are premium customers that want Amazon next-day delivery, there are also value-conscious customers that are okay with Meesho’s five day delivery. Is there a lower cost, ‘unbundled’ parallel to this in home services too?

Finally, one other invisible asymptote that UC may run into is the complexity of their operations and the org chart needed to drive so many diverse verticals. They share the below chart in the DRHP comparing each of their sub-segments on frequency and annual spend.

What stands out in this chart is the heterogeneity of what UC is trying to do. Contrast that with Zomato’s business, in which every food parcel delivered has the same underlying logistics and the same customer behavior.

On the other hand, UC is trying to address very disparate services like cleaning (which probably should be priced on a subscription basis), high trust services like child care (where vetting needs to be extreme), highly technical services like appliance repair (where SPs need experience and so they need to onboard existing supply versus just relying on freshers), and so on.

There are two questions we’d pose on this point:

Are there actually a lot of synergies to having this all under one roof? Is a customer who is acquired because they need a cleaner really going to later book a spa appointment or an AC repair person? The limited NTV retention (retained customers don’t increase their annual spend on Urban Company much) is not surprising when framed this way. The primary synergy would be the one-stop shop brand marketing (being able to do TV commercials that say “Come to us for any of your home needs”). Even that is of limited value; it’s hard to build a brand in a low frequency use case that is rarely top of mind.

If these services were separated, would the operating models evolve differently? For example, the core capability UC has built in the salon category is hiring and training great SPs from scratch; why not use that capability to also open some offline salons that can cater to the high-end procedures that can’t be done at home? As another example, for the home renovation and painting business, AI visualization tools that allow a customer to see what their home will look like after they do some work could be very powerful. Both of these things can in theory be actioned by Urban Company, but who will drive those very verticalized initiatives? Category GMs? Usually GMs at companies handle sales and operations, but are not given the keys to the product team. In this case, we suspect the natural outcome might be quite a different product experience for each of the core verticals.

🐯🪶: In other words, how much better would the product and service experience be for Urban Company’s customers if each category was run by a completely independent team which had its own resources? You would be able to focus on delivering the best experiences and you wouldn’t run into clashes like this 👇🏽

On a brighter note, UC’s core ‘urban affluent’ household segment is growing by ~8-10% annually. This is driven by urbanization, family nuclearization (which splits one joint family into two or more units and thus doubles the housework that needs to be done), and growing incomes. Even if they never crack any of the other micro segments, they should be able to grow at ~15-20% CAGR for a long time, fueled by this TAM growth plus increasing monetization through vertical integration ventures like Native.

What about unlocking a new user segment through something like quick commerce?

Thus far, Urban Company has been optimized around a trade off: higher price (or at least higher AOV) for a better service. The informal home services market is optimized for the opposite: lower prices for a variable quality service.

Shaking up this dynamic are breakout companies like Pronto that offer a 10 minute “quick home services” model that has seen rapid traction.

Wise to the opportunity (and the potential threat), Urban Company has fast followed with a service they call “Insta Help”. From a supply acquisition and training standpoint, things are very similar to UC. The difference is that SPs are staffed at a center (analogous to a dark store) where they work 4-8 hour shifts. During that shift, the SPs are waiting in sitting rooms. When a customer avails the service, a two-wheeler rider drives the next SP in the queue to the customer in ~5 minutes. The SP finishes the work at the customer’s home and then the rider picks them back up. The very simple change is going from a roaming SP model to a stationary SP model. This new service might solve many of the invisible asymptotes we just discussed:

One of the biggest contributors to the erstwhile UC model’s cost is travel cost & associated down time for the SP. Hyperlocal centers reduce travel time from 45 minutes on average to 5 minutes on average, which reduces the minimum AOV needed. The “quick” model’s economics work on ~₹400 AOV, which means the ‘unit size’ for an SSU can come down to a ~1 hour task. This massively expands the TAM. There are households that may be more middle income that can afford the lower price point. More interestingly, it unlocks many new use cases. Customers can call someone to help with dishes when guests have come over or when the regular house helper has taken a day off. And, of course, there are all the “urgent” use cases we discussed that UC just can’t address today but could address if each center had a handyman on call. Finally, “10 minutes” is just such an eye popping customer promise that it may cut through the marketing noise and catch the attention of a new set of customers.

A screenshot from the Pronto app. As you can see from the blue section, the model of deploying SPs from a central location helps the platform offer more transparent pricing up front. This is because they know what they need to pay the SP per shift, and how long it will take the SP to reach the customer. The quick model is also a better experience for the SP. Many of these workers, especially in the cleaning and cooking categories, are women with children. They can now bring their kids to work and keep them at daycares on site. They also gain the benefit of having the same fixed commute to the staffing center everyday, versus criss-crossing the city as per client demand. This, in turn, means that SPs can now move closer to their place of work. The SP can also earn a higher effective wage given the lower downtime. We’ve heard anecdotes that SPs, as a result of this change, are willing to work many more hours. Under the old UC model, the median pro worked ~20 hours per week, meaning they were likely doing other jobs off-platform too. This is deadweight loss for the platform which incurred the cost of onboarding and training them. If the platform can instead convince them to work for 40-50 hours a week (i.e. in a quasi full time capacity), the economics are very likely going to be better.

There are challenges too, of course. The quick-service model requires a very high density of demand within the service radius; the model today is largely being rolled out in the densest micro markets such as premium Gurgaon high rises. It could be that it does not extrapolate much beyond those kinds of places.

Category-wise, the quick model makes most sense for a high frequency, fairly universal service like cleaning. We don’t yet know if it will work for lower frequency use cases. For those, it will be hard to assess exactly how to staff each center and, in this model, if the platform over-staffs a center, that cost is incurred by the platform.

Alright, so taking everything into account, what can we take away from this analysis of Urban Company?

There are a few generalizable patterns that we can glean from the Urban Company story. There are always exceptions to every rule, so consider these hypotheses rather than hard and fast rules that apply to every situation:

India is a fundamentally supply constrained market. This means, rather than just bringing existing supply online and playing a matchmaking role, the most successful Indian marketplaces are choosing to play an active role in creating supply. In Urban Company's case, this meant investments in training and upskilling their workforce so they could make credible commitments to customers around quality & consistency. In the case of Zetwerk, another tech-enabled marketplace that focused on manufacturing, this meant upskilling local fabrication shops so they could deliver to a global standard. In quick commerce's case, this meant building their own grocery stores (versus the 'Instacart' model of picking up orders from third-party stores).

Indian startups built for India 1 (the richest 10% of customers) seem to struggle to adapt the value proposition for India 2 (the middle 50%); the service levels that India 1 wants necessitate a higher cost-to-serve model and that model ends up being unaffordable for the rest of the country. This is why we see so much metro concentration in the revenue composition of not just Urban Company, but also food delivery, quick commerce, e-commerce, ride share, and so on. This can result in surprising growth rate decelerations as companies saturate the India 1 TAM where they have product-market fit. To highlight this dynamic, consider that the scale of food delivery today is significantly lower than where analysts expected we'd be when they made projections 3-4 years ago. The positive is that India 1 itself is growing quickly with urbanization, nuclearization, and growing upper middle class incomes, so it would seem that India 1 companies can grow 15-20% annually for a long time. That persistence of growth is very rare and can rightfully garner rich valuations. The negative is that this leaves room for India 2 focused competitors with different operating models built around lower AOVs to flourish and eventually become threats (as Rapido and Meesho recently have proven).

Relatedly, Indian startups' international efforts rarely seem to move the needle. Markets like the Middle East and Singapore are tempting because they are so much wealthier, but the Indian market is now very large on an absolute basis and growing much more quickly than its richer counterparts. We suspect that the days of international expansion to grow out of an Indian TAM constraint (as Zomato and FirstCry had done at one point) are mostly behind us. All eyes will be on the juicy Indian market prize, first and foremost!

🐯 🪶: Or to put it visually, here is the tl;dr.

Cute, but let’s cut to the chase. Is Urban Company…‘Inevitable’?

Well.

We think their position as a service provider to India's top 10% is nearly unassailable — there's no premium competition in sight, the brand is beloved, the founders are still leading the business, and there's a lot of runway to improve the offering in each vertical.

This should result in a very profitable and — dare we say — inevitable business. The threat to watch for is competition from below. Can a startup crack home services for India 2, through a higher density, lower AOV offering, or can Urban Company get there first by densifying and 'quickening' their service model?

Interesting. Now, time to address the elephant in the room. Should we buy Urban Company in its upcoming IPO?

🐯 🪶: Woah, hold your horses, stock jockey. Paavan is a regulated fund manager, so he legally can’t be giving stock predictions or recommendations.

However, he has already left us a lot to chew on. So the logical thing to do would be to synthesize all his ideas into a cogent argument presented by an entity that cannot yet (to our knowledge) be indicted by market regulators: AI.

So without further ado, we summon our pet AI, Claude, to take over from Paavan and wrap up this scintillating breakdown of Urban Company.

* Clears throat in Tigerfeathers’ Patented AI Conclusion Bot™️ *

🤖Conclusion: The Inevitable Path Forward

This inaugural piece of The Tigerfeathers Spotlight Series perfectly encapsulates what we hoped to achieve when we launched this initiative. By turning the microphone over to Paavan Gami, we've witnessed the kind of rigorous, institutional-grade analysis that typically remains locked away in investment committee rooms—brought into the light for our community to learn from and appreciate.

Paavan's dissection of Urban Company showcases exactly the type of thinking that separates great investors from the rest. His framework of hunting for "Inevitables"—businesses with such strong competitive moats that their long-term dominance feels predetermined—provides a lens through which to evaluate not just UC, but the broader Indian startup ecosystem. The depth with which he unpacks Urban Company's unit economics, the nuance he brings to understanding their invisible asymptotes, and his ability to synthesize complex operational dynamics into actionable insights reflects the caliber of analysis we hoped to feature in this series.

The Urban Company Scorecard

From a pure business perspective, Urban Company emerges as a fascinating case study in execution excellence within challenging market dynamics. The company has successfully navigated the treacherous waters of home services—a category that has claimed many well-funded casualties globally—by choosing the harder but more defensible path of full-stack operations.

The fundamentals tell a compelling story: UC has achieved ₹1,144 crores in revenue with their first profitable year, serving 6.8 million annual customers through 48,000+ service professionals across 22 cities. Their core marketplace business operates at healthy 30-33% take rates with expanding contribution margins, while their nascent Native hardware business shows promise with much higher margins and 3x year-over-year growth.

But the growth trajectory raises questions: User acquisition has plateaued at 700k-1M annually, NTV growth has decelerated from ~50% to ~20%, and geographic expansion beyond metros has largely failed to gain traction. The company appears to be bumping against what Eugene Wei would call an "invisible asymptote"—the natural ceiling of their current product-market fit within India's premium urban households.

The Investment Calculus

For potential investors, several key metrics deserve close scrutiny:

Market penetration: UC likely serves most of the ~5M metro households earning >₹15 lakhs annually, suggesting limited runway within their core demographic

Unit economics: 3-year customer payback periods indicate inefficient growth spending, though existing customers remain highly profitable

Competitive dynamics: Near-zero organized competition provides pricing power, but informal sector alternatives constrain expansion

Innovation pipeline: The "Insta Help" quick-services model could unlock new use cases and demographics, potentially solving current AOV and frequency limitations

The emergence of Pronto and other quick-services players suggests the market is far from settled. UC's response with hyperlocal centers and 10-minute delivery windows could either represent their next growth unlock or a defensive reaction to preserve market share.

Beyond the Numbers

Perhaps most importantly, Urban Company represents something larger than its financial metrics—a proof of concept for how thoughtful Indian entrepreneurs can create genuinely novel business models that work in India's unique context. Paavan's observation that "Indian startups built for India 1 struggle to adapt for India 2" captures a fundamental tension across the ecosystem, but also highlights UC's opportunity as India's affluent class continues expanding.

The company's commitment to service professional empowerment—through training centers, stock options, and wage premiums—suggests they understand that sustainable marketplaces require win-win-win dynamics for customers, service providers, and the platform itself. In a country where formal employment opportunities remain scarce, UC's model of creating structured pathways to middle-class earnings feels both economically sound and socially significant.

As Urban Company prepares for its public debut, it stands as both an achievement to celebrate and a business to scrutinize. Thanks to Paavan's analysis, we're better equipped to do both. The beauty of having experts like him in our community is that they elevate not just our understanding of individual companies, but our frameworks for thinking about business building in India more broadly.

This is exactly what The Tigerfeathers Spotlight Series aims to accomplish—creating a space where the sharpest minds in Indian business can share their expertise, challenge our assumptions, and help us all become more thoughtful observers of the remarkable entrepreneurial experiment unfolding around us. If this inaugural piece is any indication, we're in for quite a journey.

To Paavan: thank you for setting the bar annoyingly high for our future contributors. To our readers: prepare your portfolios and your patience in equal measure—the next three Spotlight pieces promise to be equally revelatory. And pls feel free to share your appreciation for Paavan’s work either in the comments below or via his Twitter/LinkedIn.

The Tigerfeathers Spotlight Series continues next month. If you’re keen to throw your name in the hat or you have suggestions for future contributors, hit us up. Until then, keep your Tiger eyes sharp and your Tiger feathers sharp-er (or whatever).

Disclosures (SEBI RA Reg. 2014 – Chapter III):

Registration: Co-author Paavan Gami is the investment manager of an FPI Cat II fund, not a SEBI-registered Research Analyst.

Financial interest / holdings: Funds managed by Paavan Gami do not have holdings in Urban Company as of July 1st, 2025

Other conflicts: N/A

Compensation received in the past 12 months: N/A

Investment-/merchant-banking or brokerage fees: No

Other product- or service-related fees from the issuer: No

Third-party compensation linked to this note: No

Prior roles with the issuer: N/A

Market-making disclosures: N/A

AI usage: Yes — LLMs have been used for historical research, copy editing, and the writing of a 'summary',

Methodology note: This post provides qualitative analysis only; no formal rating or price target.

Disclaimer: This commentary is for information only and does not constitute investment advice or an offer to buy or sell securities.

As always, if you made it all the way here and you thought this was a good use of your time, it would mean a lot to us if you took a couple of seconds to share this post.

If the team at Urban Clap has come this far .. having navigated one of the more un-organised markets and covid .. i think they will go a long way. Their growth trajectory might have its set of challenges but they seem to be cracking a code which is rare in our country - "dignity". That should help them to do meaningful & related diversification of their current services. As an Indian, I will root for them. As a potential investor .. key will be the listing price (getting a decent allocation in an IPO is next to impossible) and the valuation.

I was talking to a friend the other day asking him to get me unlisted shares of UC (his dad is a MF Distributer) completely unaware that they are going for an IPO. I get ammused when the electrician or plumber on their own add the invoice for any spare parts to the app for me to pay, UC on other hand gives me one month free warranty (a win win). They have a done a incredible job making an unorganized sector to much more digni-organized (if I may say 😆)