Hunger Inc: Empire of Taste

From Canteens to Sweet Shops, and Pedro to Papa's, how Mumbai's Hunger Inc set the table for a new chapter of Indian hospitality

Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 159 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since last week’s essay.

We’re going back to back with another story that’s been many months in the making. ‘Many months’ also happens to be the age of Vaibhav Suryavanshi, the youngest centurion in IPL history.

To stay up to date with more tales of Indian excellence, click here to subscribe👇

This edition of Tigerfeathers is presented by…Bombay Locale

“Nobody owes you attention. We help you grab some.”

Bombay Locale is a global creative studio that helps tech companies cut through the noise by turning complex ideas into compelling, cinematic stories. Their masthead says it all: "Storytelling that works."

Over the last 8 years, they've crafted explainer films, launch videos, brand campaigns, and investor content for companies like Zoho, Hubilo, Pingsafe, InVideo, Defy, ClearTax, Jio, and dozens of early-stage players across SaaS, fintech, crypto, and AI.

What sets them apart is their technical chops—they’re ‘techies turned storytellers’. They believe that behind every complex product is a human problem worth solving, and that emotional connection is where great storytelling comes alive.

The company originally started as a scrappy experiment between two brothers working out of hostel rooms and friends' apartments with borrowed gear. Today it’s evolved into a colourful team of designers, engineers, bankers, filmmakers, and all sorts of misfits united by a shared love of great stories.

If you’re building in consumer, fintech, SaaS, or AI, and you’ve got a story you want to bring to life, get in touch with them at hello@bombaylocale.com, or book a call with the Bombay Locale team here:

And if you're interested in sponsoring a future edition of Tigerfeathers, hit us up on Twitter/LinkedIn or by replying to this email. With that, let’s get to it.

In Chapter One of Tom Shone’s excellent biography of Christopher Nolan is a quote from the director that pinpoints the exact moment he knew what he wanted to do with his life, as far back as his pre-teen years at boarding school in England:

There was no film club, although every week war movies like Where Eagles Dare or The Bridge on the River Kwai were shown, and Nolan does remember being allowed to watch a pirated VHS of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) on a TV in his housemaster’s lodge. “We were allowed to pop down to the master’s house and watch half-an-hour chunks of it,” he says. It was only later that he caught Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) and put it together with the film about replicants he had seen in half-hour chunks in his housemaster’s study.

“I can remember this very palpably, identifying some tone to those films that was common and not really understanding it and wanting to understand it—something that almost felt like a sound, a low throbbing, a particular lighting, or an atmosphere to those films that was clearly the same. Then what I found out was, same director. So, totally different story, different writers, different actors, different everything, all the things that as a kid you identify as making films what they are—you think the actors basically make the film up—all those things are different, but there’s a connection, and that connection is the director. I can remember thinking, That’s the job I want.”

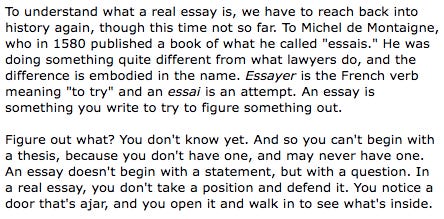

Spoiler alert - today’s piece has nothing to do with lighting, movies, or directors. It does, however, have to do with genre-bending creativity, storytelling, and execution of the highest calibre (also, ceviche). Much like the paragraphs above, it was born out of pulling at the same common thread.

In June last year I was putting together my ‘GOAT list of Mumbai food recommendations’ for a friend visiting the city from the US for the first time. It hit me that, since 2015, the real estate on that list has been increasingly claimed by the same juggernaut force, comprising the trailblazing team of founders, chefs, restauranteurs, mixologists, and mithaiwalas at Hunger Inc.

Starting with the launch of their iconic opening salvo The Bombay Canteen in 2015, the company has built a portfolio of enduring brands that routinely command the territory on any (more-official-sounding-but-less-prestigious) list of the best restaurants and bars in Mumbai, India, or Asia.

Before going ahead, I’m contractually obligated to add here that many of Mumbai’s best meals aren’t found within four tastefully decorated walls, surrounded by moody lighting or air conditioning; several of the city’s best dishes are served without the fuss of chairs, tables, crockery and even cutlery; and you don’t need to break the bank to sample the best that the metropolis has to offer.

But when it comes to restaurants (i.e. the kinds of places that pop into your head when you think of restaurants), over the last ten years there is no group that is more responsible for changing the dining scene in Mumbai - and arguably, India - than Hunger Inc.

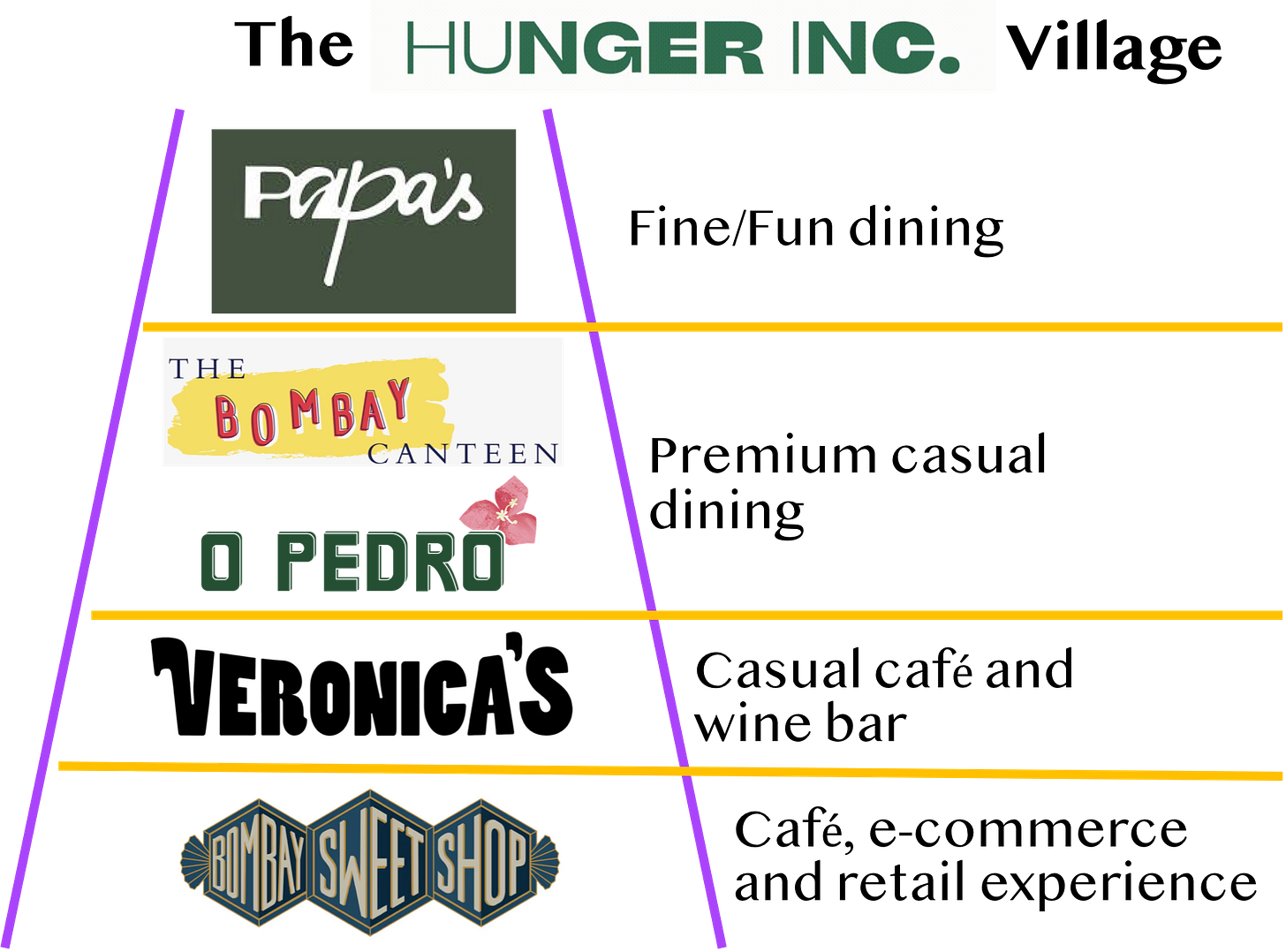

Originally conceived around a mission to ‘celebrate India through its food traditions’, at last count, their empire spans:

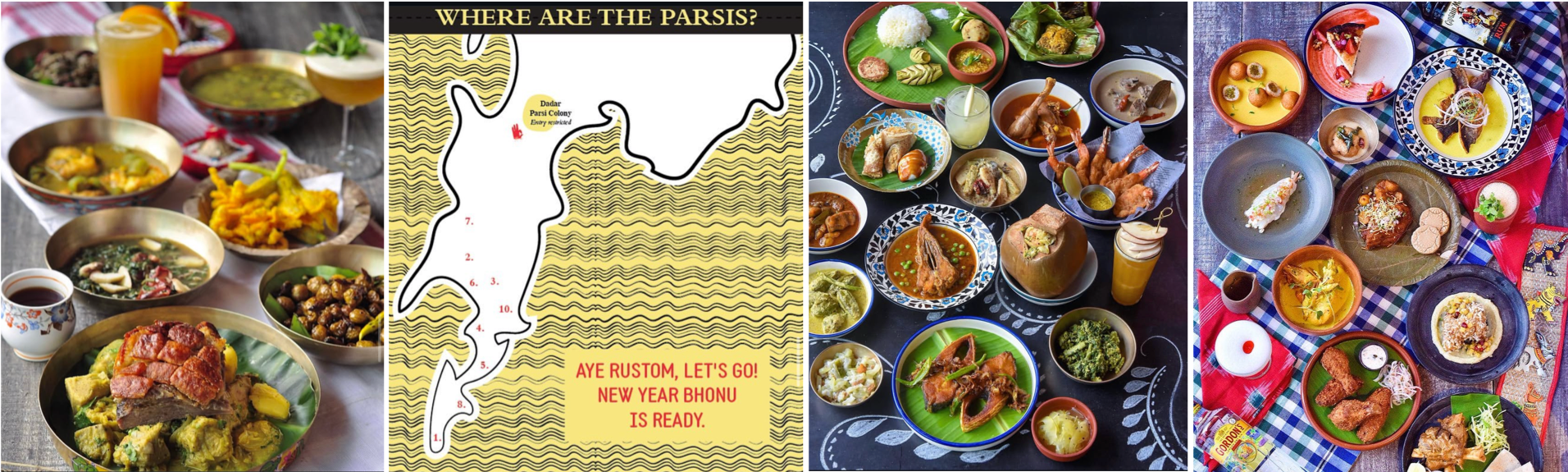

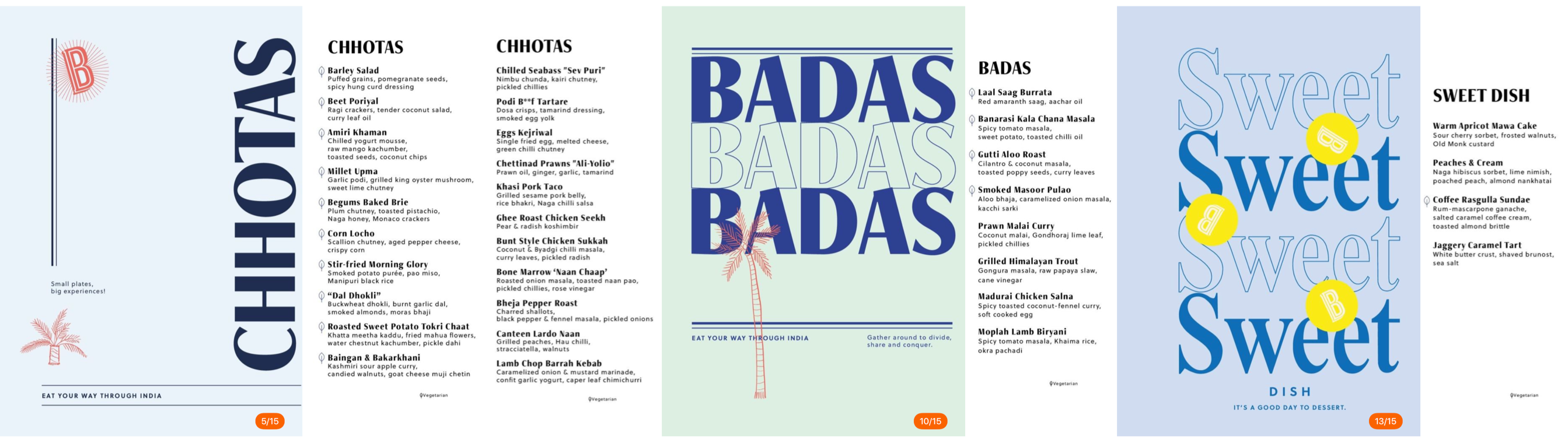

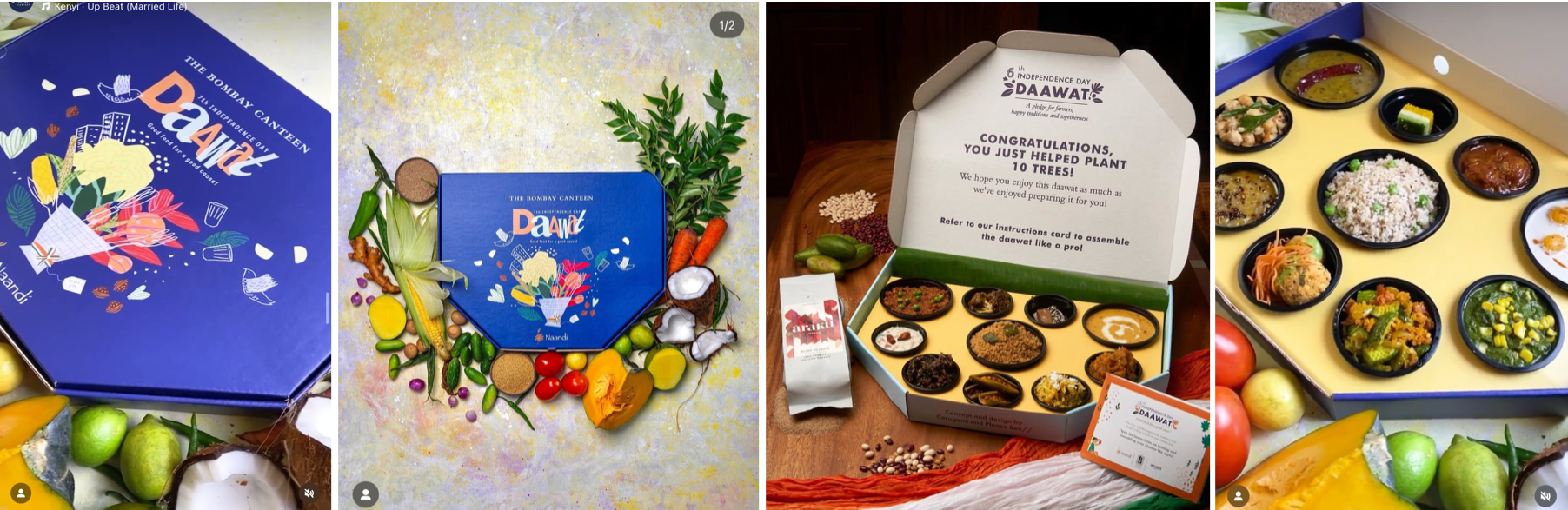

The Bombay Canteen (2015) - a love letter to *Indian* food that broke all the rules - no butter chicken, no white table cloths, no need for a nap after your meal. It’s the restaurant that redefined Indian dining in 2015, bringing the tradition of seasonal ingredients and regional cuisines into a modern, approachable setting.

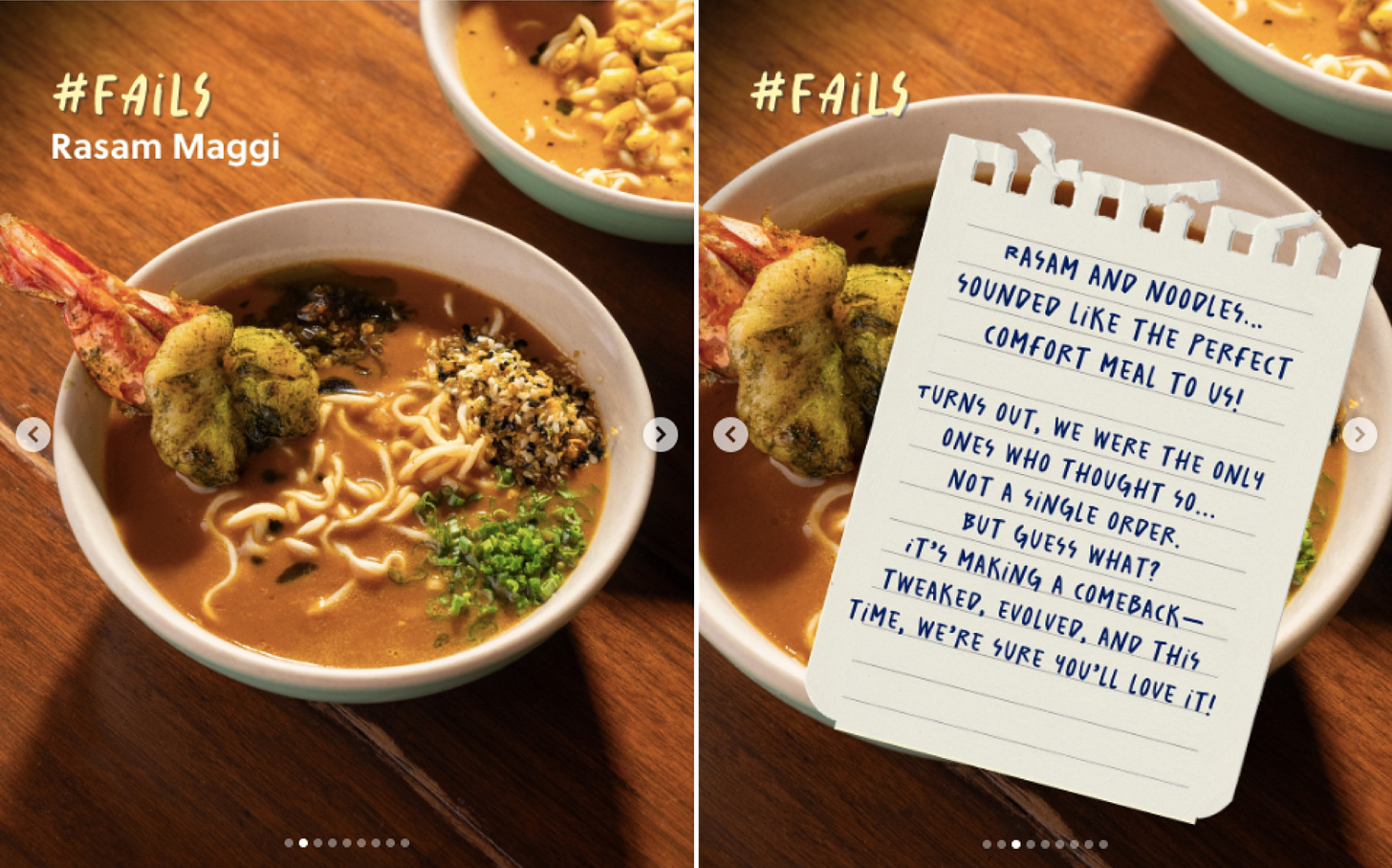

O Pedro (2017) - a “happy place” that celebrates the culture and culinary heritage of the sunshine state of Goa.

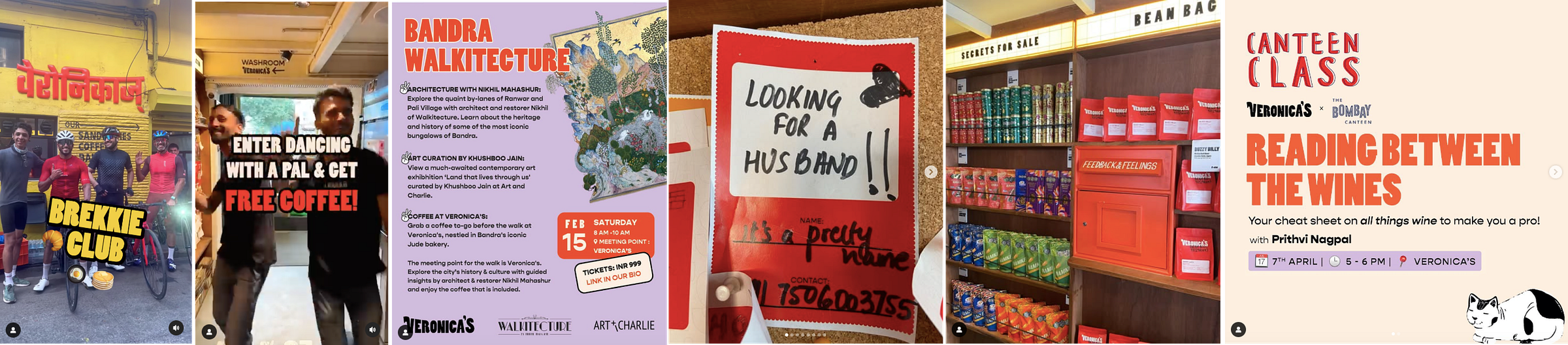

Veronica’s (2023) - the “sandwich shop with the personality of a cocktail bar”.

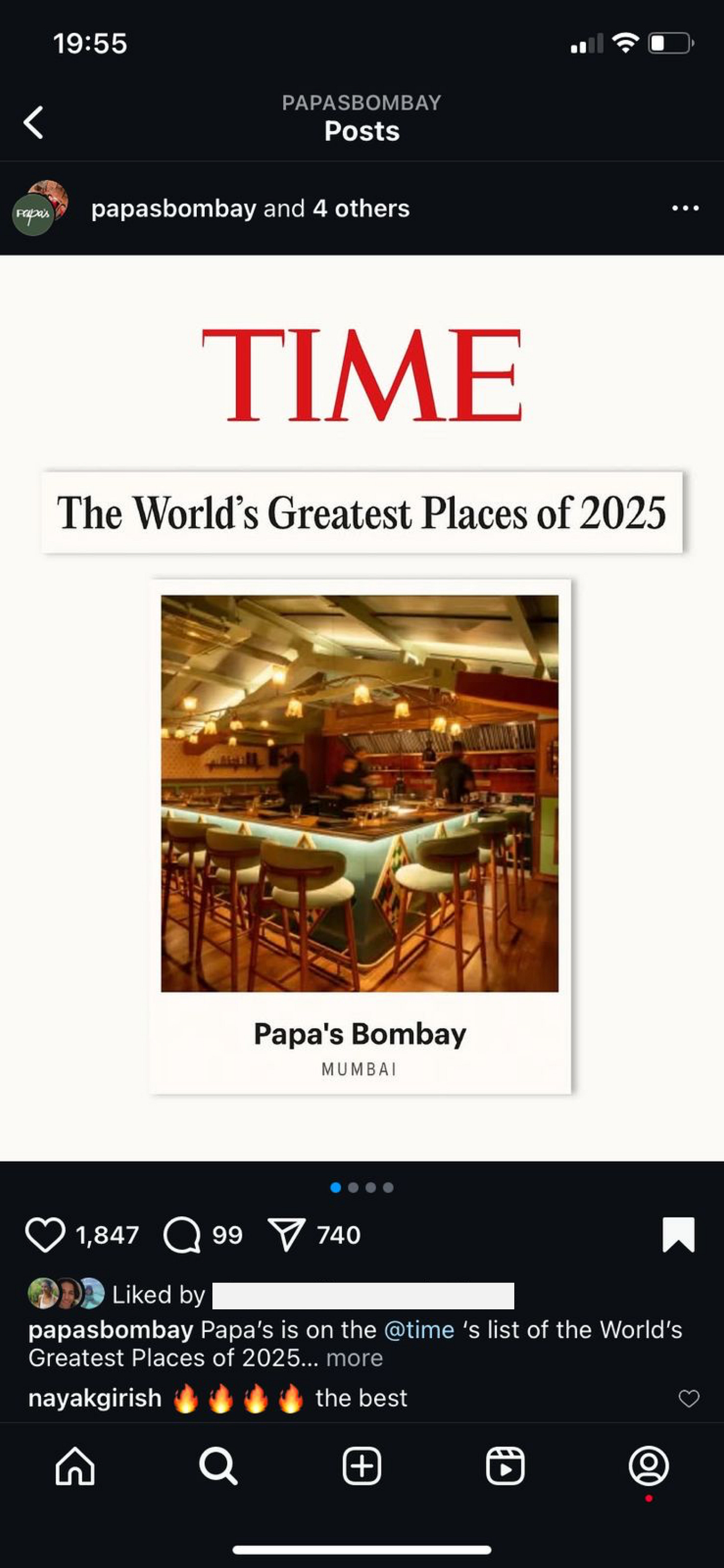

Papa’s (2024) - an “intimate-yet-loud” chef's counter experience, that fulfils their decade-long vision to reimagine fine dining in India. It serves as the culinary playground of Chef Hussain Shahzad - coronated in 2024 as the best chef in the country.

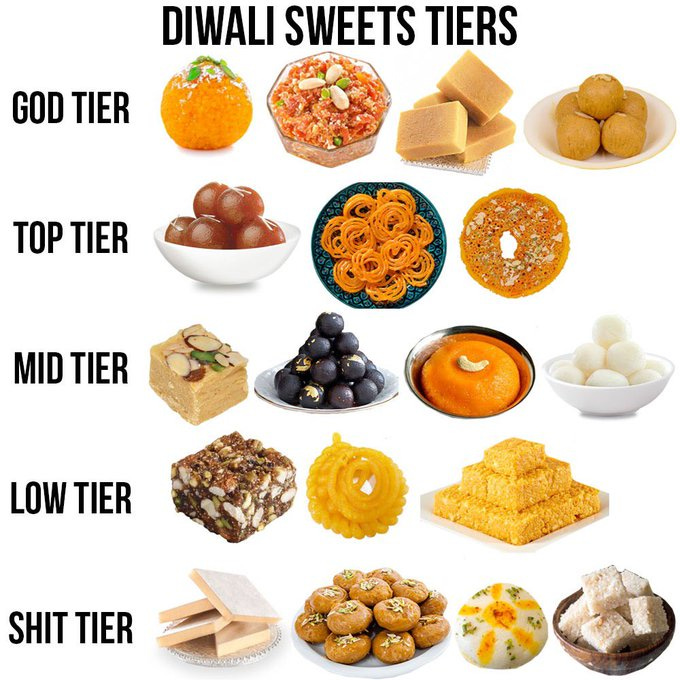

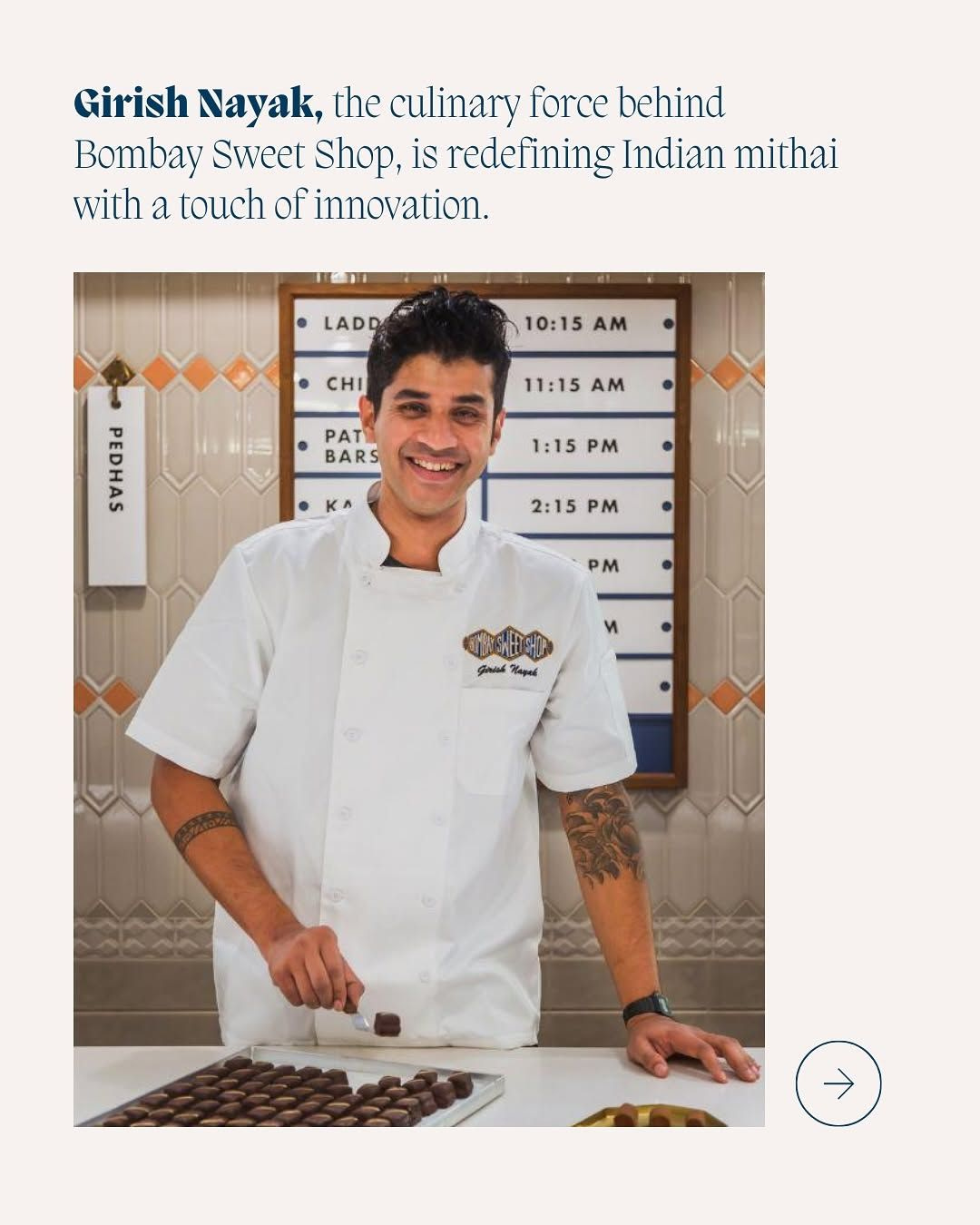

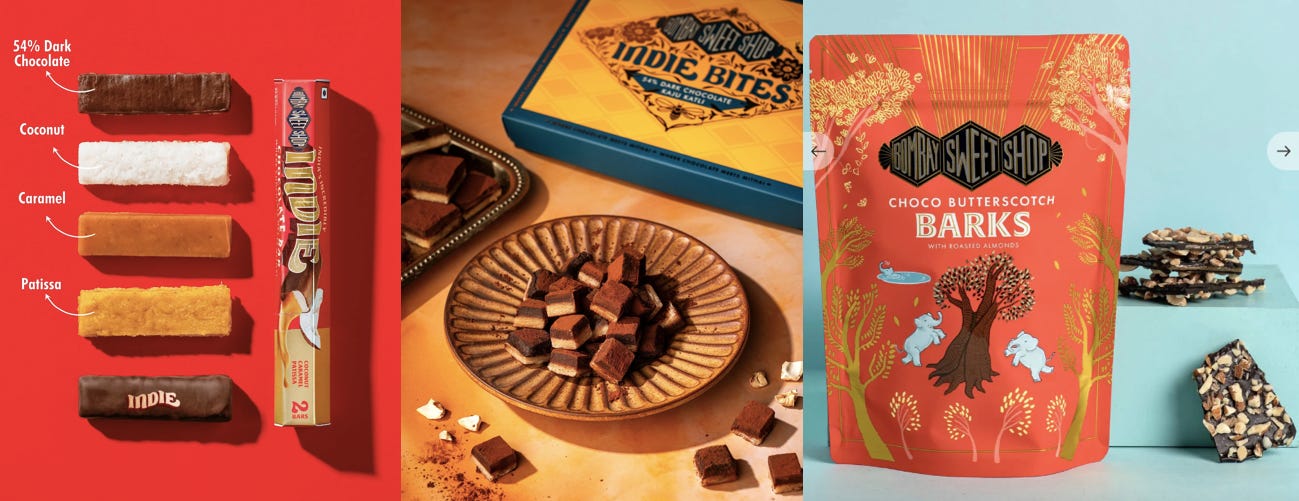

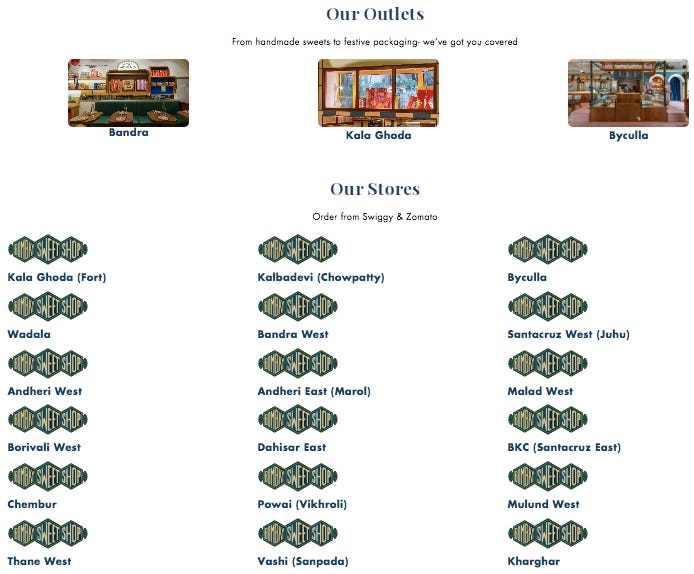

Bombay Sweet Shop (2020) - a project that began by asking “What if Willy Wonka owned a mithai factory?”, that’s now blossomed into a formidable direct-to-consumer brand celebrating the magic of Indian sweet-making.

and, enthucutlet (2022) - a bi-monthly digital magazine chronicling the ingredients, people, places, legends and recipes that are shaping the story of food in India, extending the company’s mission beyond the walls of their restaurants.

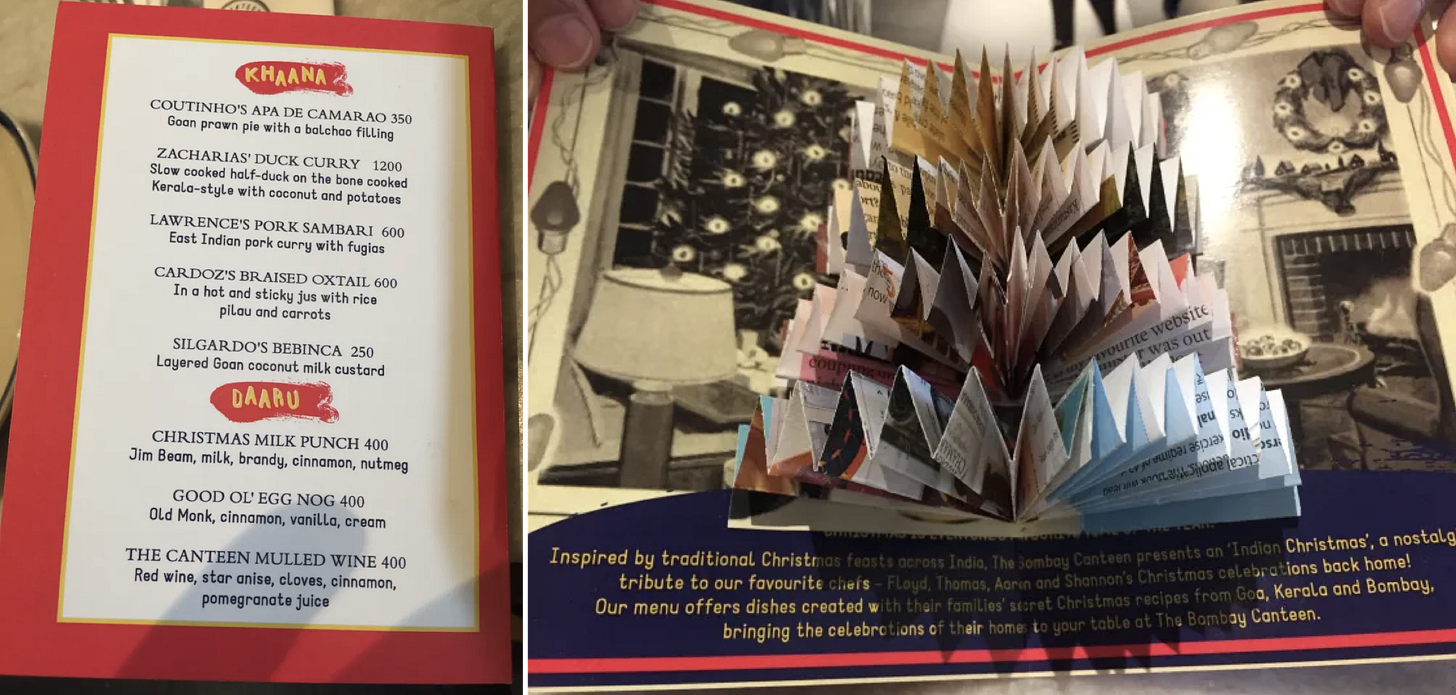

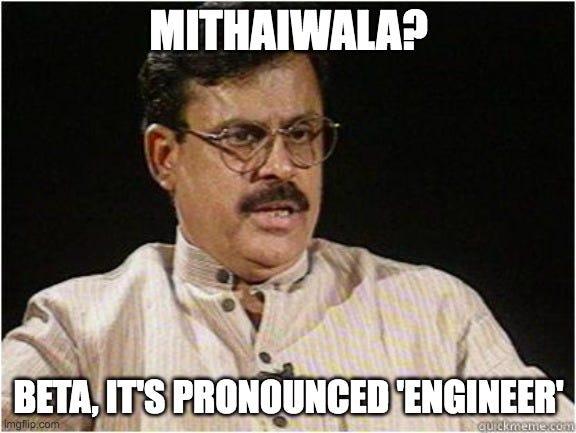

Hunger Inc was originally founded in 2015 by Sameer Seth and Yash Bhanage, alongside their mentor and culinary North Star, the legendary chef Floyd Cardoz, whose visionary approach to Indian cuisine at his New York restaurant Tabla first made him a culinary icon in America. Chef Floyd sadly passed away at the start of the 2020 pandemic. While the team is still very much animated by the inventiveness and playfulness of his original approach to food, the company has today blossomed into a food services powerhouse. It counts on the leadership of Executive Chef Hussain Shahzad and Chief Mithaiwala Girish Nayak, amongst a wider cast of chefs and operators that includes several of the country’s best.

Over the last decade, the group has crafted a culinary philosophy and a coda on hospitality that has tied together each of their subsequent ventures. Much like how Ridley Scott's directorial DNA threads through both space-horror and android-noir, there’s an unmistakable Hunger Inc signature that connects everything they touch. And it extends beyond what happens in the kitchen.

If you live in Mumbai or you’ve visited in the last ten years, and you’re the type of person who likes going out to restaurants, there’s basically a 100% chance you’ve wandered into their world. It’s likely you’ve experienced their signature brand of hospitality firsthand, where their front-of-house staff makes it clear that they’re on your team, where every detail - from the copywriting in the menu to the layout of their spaces to the enthusiasm of staff members passionately talking about their favourite dishes - has been meticulously crafted to put you at ease.

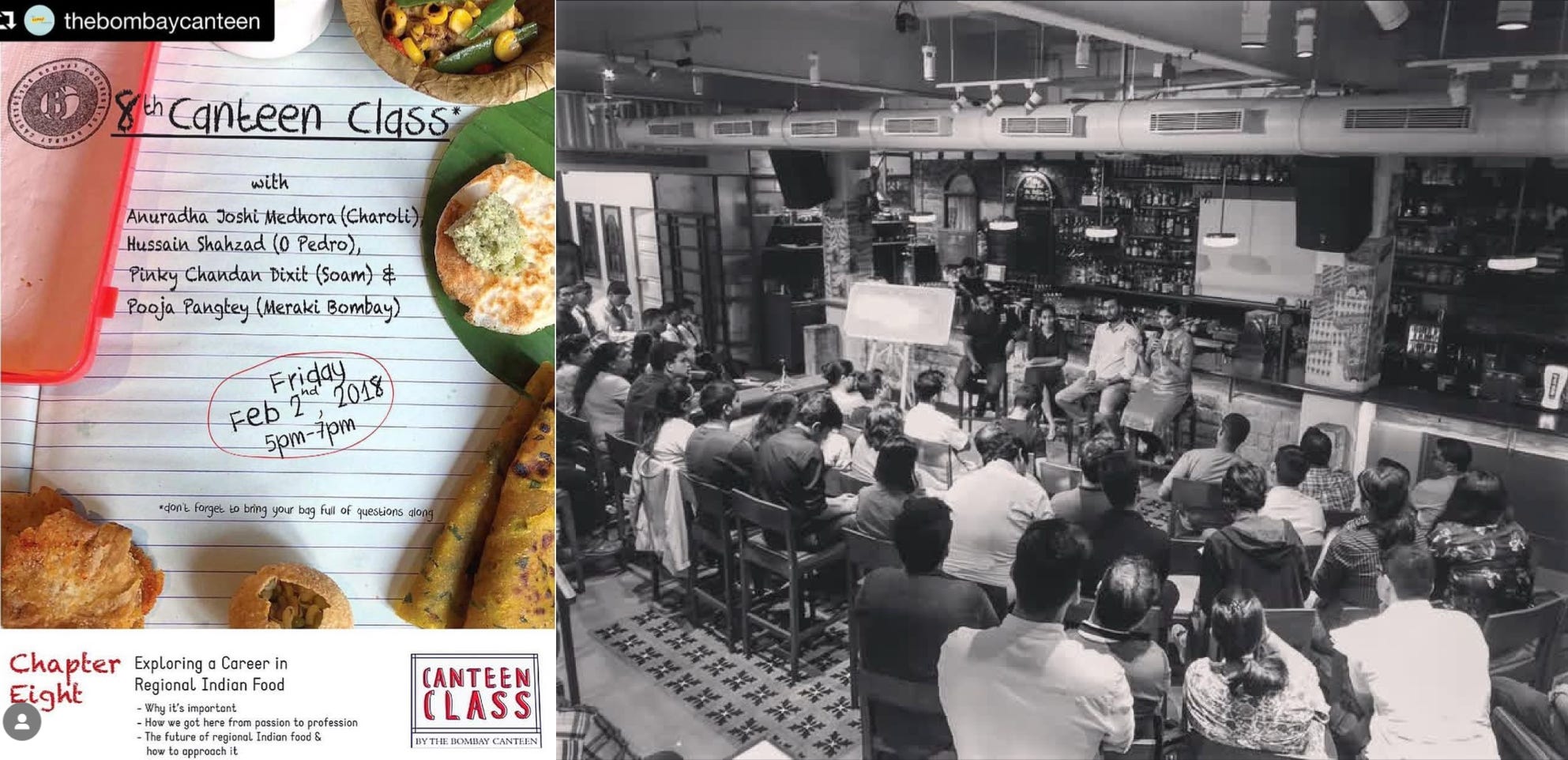

Back in 2015, when India didn’t have much of a standalone restaurant culture, it wasn’t intuitive for restauranteurs to care about these things. What helped the Hunger Inc team break the mould is that they were bringing the knowledge and experience from years working with titans of the food industry in the US and Singapore. It meant they were amongst the first Indian restauranteurs to think of eating out as an ‘experience’, working backwards from how a restaurant should make its guests and - more importantly - its staff feel.

Today this philosophy has become their calling card. Coupled with their thoughtful approach to reinventing regional Indian dishes, they’ve been able to rack up a pristine record of hits in a notoriously unforgiving industry, giving them bragging rights as a special set of impresarios, operators and tastemakers. So, as they celebrate their 10th anniversary this year, it seemed like a fitting juncture to document their story for Tigerfeathers.

“B-b-but this is a tech newsletter”, I hear you say.

This is true. Our last three Indian startup stories were about a company that designs mRNA vaccines, a company that makes it easy for Indians to buy digital gold, and a company that makes special satellites that allow us to spot invisible problems on the surface of the Earth.

So why is today’s piece - our longest ever - about a company that makes a mean Chilled Seabass Sev Puri and Dark Chocolate Kaju Katli? Three reasons:

1. Because the Hunger Inc story isn't just about restaurants - it's a primer on creating things that people love.

The team has cracked some timeless codes on things like world-building; storytelling through products; nurturing cult brands; designing for your community; and more. Their ‘Hospitality-First’ ethos can be applied to supercharge virtually any entrepreneurial pursuit. They just happen to be using food as their canvas.

If you’re in the business of getting people through the door and making sure they come back again and again, you will probably find a something to chew on here.

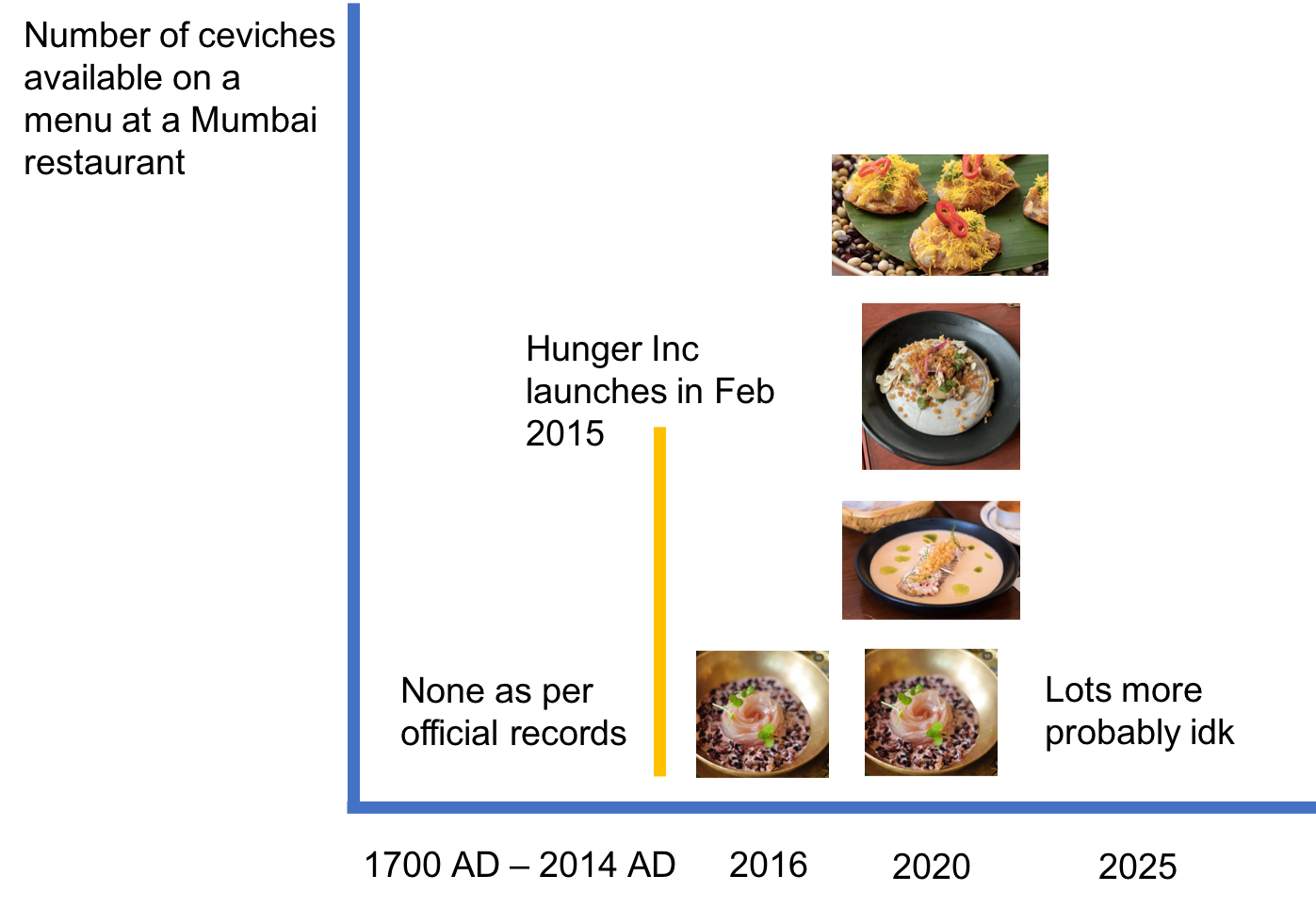

2. Because their story coincides with a broader plot twist in the Indian consumer saga.

After decades of nurturing a reflexive preference for anything with an overseas stamp, India's taste buds (and wallets) are pivoting homeward. As we put more distance between ourselves and the post-liberalisation 1990s, a ‘foreign-made’ infatuation is giving way to a growing curiosity about our own styles and flavours.

You can see this changing zeitgeist everywhere from fashion labels to speciality coffee to skincare. It’s a combination of Indian entrepreneurs being bold enough to test the adventurousness of Indian consumers, and Indian consumers opening up to the idea that Indian-made doesn’t have to be an apology, it can be an aspiration.

In the same vein, the arc of The Hunger Inc - from elevating humble regional Indian cuisines to reimagining mithai for the Instagram age - isn’t just a food tale, it's a snapshot of a country rediscovering its own richness.

3. Because food is home turf (for me).

I’ve grown up in a family of professional chefs, bakers, and restauranteurs, where the background noise at home was always conversations about food. My parents used to run two much-loved cafes in Mumbai - PLENTY and Food For Thought - for over ten years until the pandemic. After many, many occasions walking out of a Hunger Inc establishment saying some variation of ‘they’ve figured something out here’, it felt like the easiest way to figure out what, was to just ask the team myself. So this piece is an excuse for me to nerd out about a space that’s close to home, while getting to learn from some of its sharpest operators, at a time when India’s appetite and curiosity for new food experiences is at an all time high.

If you’re curious about the industry, if you’re a fan of their restaurants, or if you’ve got a tiny back-of-your-mind interest in running your own some day, you will enjoy diving in to this one.

With that being said, today’s Tigerfeathers essay will cover:

the 10 year journey of Hunger Inc

a (very) deep dive into the ideas, insights, individuals and intuition that’s shaped each of their ventures

their process of researching and launching new businesses, and their (secret) recipe for generating hits 👀

how their story fits into a changing paradigm for consumption and entertainment in India

A quick disclaimer before we start. You know how sometimes you get to the end of a book and, in your head, you're like "*angry noise* this could have been a blogpost!"? Well, this is the exact opposite of that - it's a blogpost that could have been a book. English translation - it's long AF. In my defence, it’s one of the most colourful startup stories you’re likely to find, and because this is Tigerfeathers, I thought it was important to do it full justice. All of which to say, I would budget for a few sittings (and bathroom breaks) if you decide to read on.

So, without further ado (but really after far too much ado), fresh off their 10-year anniversary, this is the story of Hunger Inc.

“All they know is that you’re trying to get to the city of gold, and that’s enough. Come on board, they say. We’ll adjust.”

— Suketu Mehta (Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found)

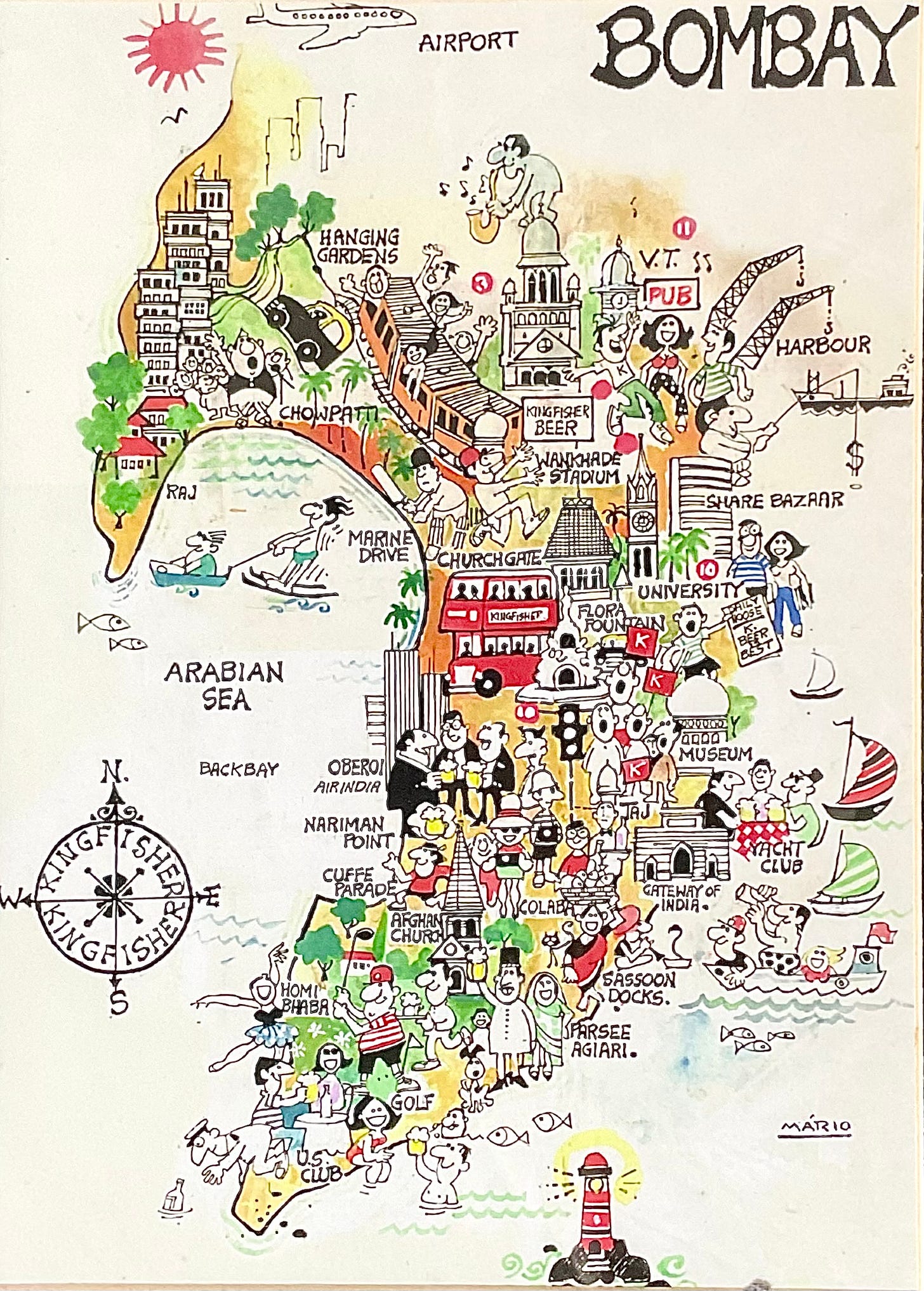

Outside the Gateway of India on Mumbai’s southern fringe, a stone's throw away from where the last British troops departed in 1948, sits a plaque that reads "Urbs Prima in Indis" – the First City of India. It is an unlikely moniker for what was once an archipelago of seven sleepy fishing islands, but Mumbai has always fancied itself a city of second acts.

It's a city where Victorian Gothic spires face off against Art Deco curves, where wine bars now fill the brick shells of cotton mills that powered its industrial revolution. For centuries, it’s been India's front door to the world – where ideas, ingredients, and ambitions wash up on its shore, get mixed into Mumbai's mosaic and presented as something entirely original. While Bangalore writes code and Delhi drafts legislation, Mumbai stirs the pot – literally and figuratively – as the country's cultural crucible. The city’s tables tell this story best.

From mawa cakes at century-old Irani cafes, to coastal fish curry houses run by Koli fisherfolk, to the flavours of Indian-Chinese birthed by Hakka immigrants and everything in between - each kitchen bears evidence of a community that came and cooked.

It is fitting, then, that the city that turned no one away would serve as both canvas and character for a genre-defining experiment in hospitality. When the founders of Hunger Inc returned to Mumbai in 2015 after their adventures working in restaurants, bars, and hotels overseas, they would place their bet on Mumbai’s time-honoured tradition of finding possibility in the space between old and new.

1. Origins

There’s an alternate version of this story where Yash Bhanage goes ahead with his scheduled medical college entrance exam, and Sameer Seth accepts his next promotion at Citibank, and this piece is about a chain of tastefully designed healthcare clinics that make you feel comfortable yet strangely nostalgic about your health every time you visit. But we’ll never know that story.

In this one, both of them would trade the safety of their conventional career paths for the colourful chaos of the Canteen.

@YashWeCan

Yash, in particular, would abandon that path before it even began. Growing up in Pune to dad who was a neurosurgeon, his mom an architect, and an older brother who chose to be a chemical engineer, his decision to swap lab coat for waistcoat was far from preordained.

“I didn’t really have a strong idea of what career path I wanted to take.” Yash recalls. “It was either be a doctor or engineer, or just copy whatever your friends were doing. In the pre-internet days, you couldn't exactly make an informed decision on your career either. I remember there was this one career book I found that had these short briefings on different professions - almost like a dictionary of different career options - that included one and a half pages on hotel management. It said something like ‘hotel management will be a promising profession in India over the next 20 years’. That was enough for me."

In the 80s, Pune, like the rest of India, didn’t have much of a standalone restaurant culture, or much of a restaurant culture at all.

“We used to always have great Maharashtrian food at home - great fish fry, chicken curry etc, but I wasn’t a ‘foodie’ as such,” he says. “Pune didn’t have a lot of places to go out to. There wasn’t really a place we saved up pocket money for. We would go to Vaishali for a dosa in our college days, but that was it.” However, he points to one particular memory that stuck with him, that likely influenced his choice of chosen field.

“On special occasions my dad would take us to the coffee shop at this hotel in Pune called the Blue Diamond (which later became the Taj). I still remember their chicken sesame fingers. There was this manager there, always in an impeccable suit, orchestrating the entire operation like a conductor. I used to look upto him thinking 'this guy knows what he's doing’. That might have been what sealed the deal.”

Yash applied to the Institute of Hotel Management and got into IHM’s Goa campus. His parents were fully supportive of the decision to swap the familiar rhythms of Pune for the lively tempo of India’s sunshine state. The three years at college in Goa were a study in contrasts, with pristine beaches outside rivalling the dusty textbooks and outdated curriculum inside.

“I really enjoyed those three years. More than the college itself, moving out of home at 18 helped me mature a lot. I was a good student too, always in the top two of my class. It probably gave me a false sense of confidence because success in college at the time just meant you were good at following instructions written down in some outdated textbook or manual. There was no sense of the culinary arts. We weren’t exposed to what was happening around the world. The curriculum back then was taught by professors who hadn’t been part of the industry for a long time. There was nothing new. There was no attempt at instilling the passion or curiosity to create something special. The entire experience was geared towards manufacturing armies of robots for the hotel industry. It was based on discipline, not innovation.”

Case in point - when he was looking for advice on how to pick the right landing spot after graduation, his college career counsellor said “You’re a tall boy. You should work in a hotel reception.” As a naive 22-year old, he took the advice to heart, and ended up joining the newly launched Grand Hyatt hotel in Mumbai to work at the front desk.

“I got very bored very soon”, Yash admits, “but a month in, there was a conference happening at the hotel. We were really understaffed so I got pulled in to the new Italian restaurant at the hotel to help ease the load. I had never worked at a restaurant before but the hustle and bustle was infectious. The actual work was mostly clearing tables, running around getting coffee for people, that kind of thing. But I loved the idea of service, of helping people out. It was the best week I had had at work.” He asked for a switch to the restaurant side of things, and the hotel was kind enough to oblige.

Yash spent a year and a half as a server, and another year as supervisor. Even accounting for 16 hour workdays, a hellish commute, the cult of yes-sir-no-sir that permeates Big Hospitality in India, and the odd instance of entitled customers flaunting their entitlement, he felt at home.

“I started feeling like this was where I was supposed to be. Like this was my hotel, like I was meant to continue working at that restaurant forever. My dad thankfully pointed out that I was getting too comfortable. For one, I was making Rs. 12,000 per month (after starting at Rs. 8,000 per month), so it wasn’t like this was some crazy lucrative position. And two, my dad used to always tell us when we were growing up that his neurosurgeon’s job was akin to driving a taxi. When he was in the operating theatre, that’s when the meter was on, that’s when he got paid. If he wasn’t on the surgery table, he wasn’t making money. He always encouraged us to find a career that didn’t require us to always be present to earn a living.”

Realising that there was more to learn, and with the encouragement of his family, he applied to the Cornell University School of Hotel Administration, where, in Week 1, he would meet his future partner and co-founder.

@CanteenSam

Sameer was born in Lucknow, but spent his childhood bouncing between Bangalore, Kolkata, and for the most part, Delhi. He grew up in a big family that was obsessed with food. “We spent every meal talking about what we were going to eat for our next meal,” he says. “Food was always the backdrop to our most cherished memories and conversations.”

His mother was a teacher and his father in the corporate world. Despite a love of food that was regularly fanned in a family that had no shortage of great cooks, he was nudged to first fill up his CV with the kinds of things that made for a textbook career. “There was always the inkling to do something in food or hotel management as far back as college. I remember helping to organise a college festival in Delhi - it was that process of alchemy, of bringing all these pieces together and seeing the final vision come to life, I think that’s where the interest first came from. But at the time I had no idea how or where to even start. Plus in India, we tend to perpetuate this myth of ‘first do this, then you can do that’.”

That myth effectively translates to ‘first choose security, and then chase your passions.’ For Sameer that meant a degree in Chemistry from St. Stephen's in Delhi, an MBA from IIM Kozhikode, and a much-coveted campus placement into Citibank's mortgage division, that came with a ticket to Mumbai in 2005.

“I loved those first couple of years, both working in Citi and getting to live in Mumbai. It’s funny that my life has always seemed to funnel back to real estate, whether that was in mortgages at Citi, or later in the food business. It turns out banking isn’t the worst base to have if you want to run restaurants.”

After two and a half years in his role, Sameer began feeling the pull of the ‘then you can do that’ side of the proverbial Indian career equation. He couldn’t get rid of a nagging feeling that this wasn’t the path he was supposed to be on. Staring at the prospect of a promotion that felt more like a sentence than an opportunity, he decided to rip the band-aid on his hospitality ambitions.

“At 26 years old I knew I was done. This was as far as I could go. I had relocated back to Delhi by this point, so I reached out to a family friend who was a partner at this small restaurant group in Delhi and, on a whim, asked if I could join them. He was kind enough to indulge me with an offer.”

So without telling his parents, he quit his job in Mumbai and moved back to Delhi to join the Shalom restaurant group, leading his grandmother to famously quip “tum bank chhodke paratha bechne ja rahe ho?” [you’re leaving the bank to go sell parathas?].

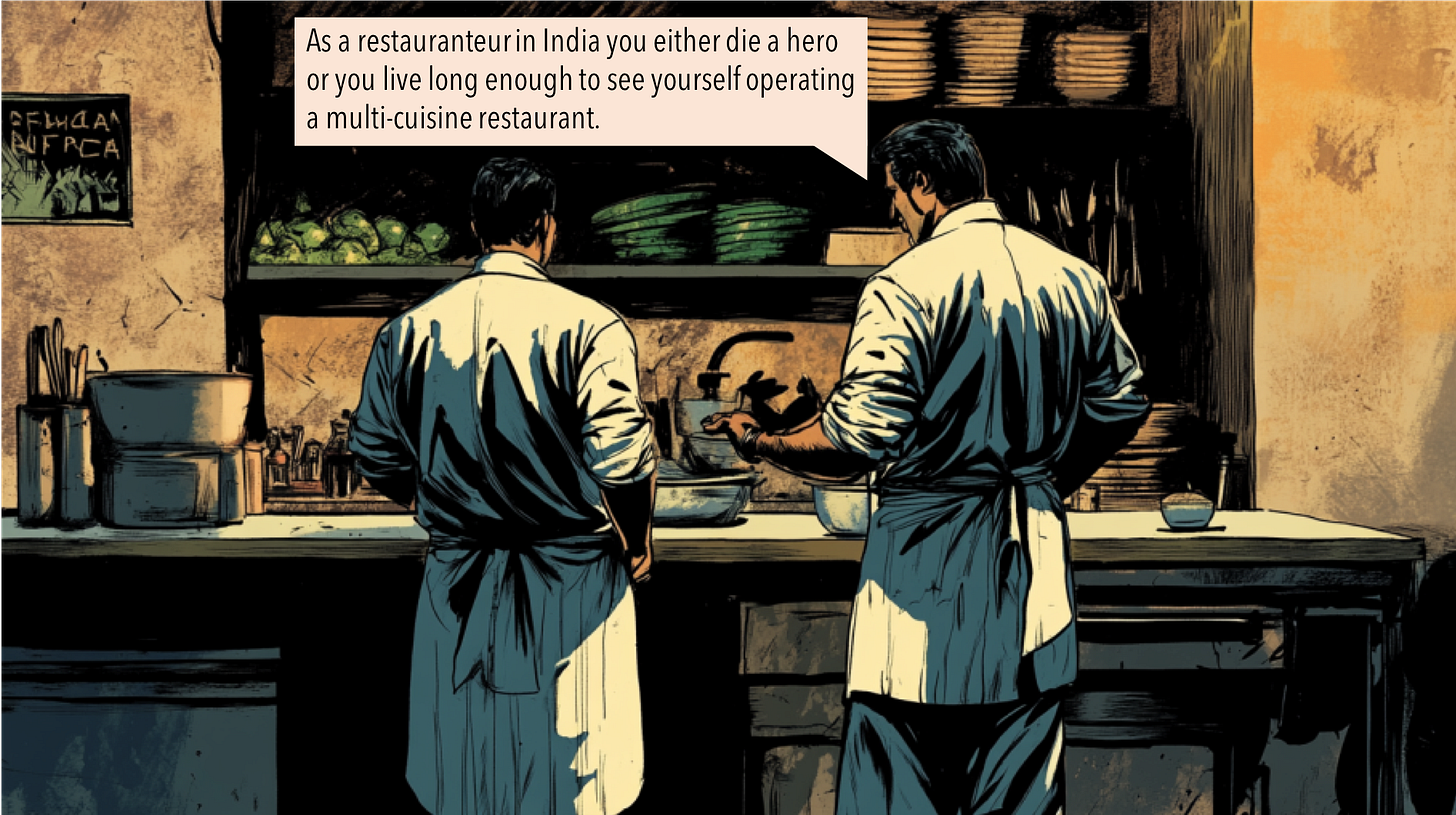

Sameer reasons that his family would have been even more horrified had they known he'd signed up without a defined role or salary. It was all academic as far as he was concerned. He had his foot in the door of the restaurant world, and that was enough. The next two and a half years would give him a front row seat to the incomparable highs, as well as the brutal mathematics of the restaurant game.

“We opened three new restaurants in the first six months, and then closed seven over the next two years. I dove headfirst into the deep end (mainly on the marketing and finance side of things), and loved every minute of it - the chaos, the rush, the joy of being on a restaurant floor…there’s nothing like it. I saw what it meant to create an ambience from scratch. I experienced firsthand what happens when shit hits the fan, and learnt as much about what not to do as I learnt about what to do.”

Just short of three years in, he began to feel the pull of entrepreneurship. “I knew I wanted to do my own thing, but there was still so much I had to learn, about how to construct a menu, how to develop a food philosophy - fundamental things like that”, he says. On the advice of a mentor, he decided to level up, and applied to the Cornell School of Hotel Administration to “find an idea to bet on.” As it turns out, he found much more.

2. Two Enthu Cutlets Walk Into A Bar

“Service is black and white; hospitality is color.”

“Black and white” means you’re doing your job with competence and efficiency; “color” means you make people feel great about the job you’re doing for them. Getting the right plate to the right person at the right table is service. But genuinely engaging with the person you’re serving, so you can make an authentic connection—that’s hospitality.”

“I believe that whatever you do for a living, you can choose to be in the hospitality business”

- Will Guidara (Unreasonable Hospitality)

For all our pithy attempts to sort humanity into neat categories, there might be just one division that matters: those who believe nothing good happens after 2 AM, and those who believe that's when the magic happens. The Hunger Inc story is a product of the latter, and fittingly for a story set in the food and beverage industry, this one starts in a bar.

In the summer of 2010, at a mixer hosted during orientation week at Cornell, Yash and Sameer were both stragglers at Rulloff’s bar on campus. “We were basically the last two left,” recalls Sameer. “We ended up hanging out till late in the night. Even back in that first meeting we joked about starting something together in India someday.”

The two would only overlap for the first six months of their year-long Masters course at Cornell. Yash would take up the option to spend his second semester abroad in Singapore. Despite their brief stint together at university, they were able to maintain a close cross-continental friendship, largely forged over a shared love of food and drink. Although both had arrived in the US on the back of years in the weeds of the restaurant business, Cornell was really their first introduction to the tao of hospitality, which meant less starched uniforms and mechanical pleasantries, and more soul and substance.

“Cornell encouraged you to ask questions,” says Sameer. “It pushed you to think deeply about whatever interested you. Your professors focused on stoking your passions, whatever they were. If you weren’t curious you were left behind.”

“It was a humbling experience,” Yash says. “It felt like everyone’s knowledge of food and hospitality was superior to mine, because mine came from textbooks and instruction manuals. The culture was completely different.”

These differences became more pronounced in their first jobs after graduation. Yash, curious about bar operations, took up a role as a bar manager with the Fairmont Hotel group in Chicago. Sameer came on board as a busboy (and then a server) at Bar Boulud in New York City, which was part of the restaurant group run by celebrated chef Daniel Boulud. Aside from learning how to carry three plates at the same time without dropping them from basement kitchen (“My proudest moment”), it was there that he witnessed this cultural disparity firsthand.

“In every restaurant in the world you have this ritual before the start of service,” he explained. “This is so the service staff can get briefed on what they need to know before customers come in. In India, this is typically a hygiene check. It’s to check if your fingernails are trimmed, if your sidelocks are groomed, if you have a lighter in your pocket that’s working in case a customer asks - that kind of thing. In the US, this was like a study group. You’re made to taste all the specials for the evening. You sample the wines. You talk through the menu for the day with everyone else. It’s predicated on you developing your own perspective on the food, so you can pass that along to guests and guide them through the evening. It was like an education instead of a box-ticking exercise, to make sure all the information relevant to shaping a customer’s experience could filter through to every level of the staff.”

This was worlds apart from Yash's experience back at the Italian restaurant in Mumbai, where servers were deliberately kept in the dark about what they were serving. "I remember we had this white asparagus festival where I could only tell guests that 'this pizza has cheese and white asparagus on it' because we weren't allowed to taste the food," he says. "I couldn't tell them the texture would be crunchy or that the asparagus would be slightly sour. Those thoughts never even entered our minds because we never experienced the dish ourselves."

Although they admit that things have probably changed today, in the early 2010s hospitality in India was still looked at in silos. Personnel involved in food, service, alcohol, decor, ambience, branding etc rarely ventured out of their respective fiefdoms. “As a waiter I was like a horse with blinders on,” recalls Yash, “My target was delivering a cappuccino in five minutes, not understanding why or how it connected to anything else. In the US you realise that, yes, food is important, but it’s like an actor in a play. It takes a lot more to make a great production, and a great restaurant is one that brings all these pieces together.”

This privileged ability, to compare their professional experiences from within and outside India, sparked an observation that would illuminate their doctrine on company-building at the yet-to-be-born Hunger Inc.

3. Black and White

“But hospitality, which most distinguishes our restaurants—and ultimately any business—is the sum of all the thoughtful, caring, gracious things our staff does to make you feel we are on your side when you are dining with us.”

“The human beings who animate our restaurants have far more impact on whether we succeed than any of the food ingredients we use, the décor of our dining rooms, the bottles of wine in our cellars, or even the location of the restaurants. Because hospitality is a dialogue, I have always placed the highest premium on hiring the best possible staff to engage our guests.”

- Danny Meyer (Setting The Table)

“In India, hospitality really means service. And service really equates to servitude,” says Sameer. "The thought that someone serving you is beneath you is deeply ingrained in the hospitality equation because of the class distinctions that unfortunately surround us all the time in India. It leads to a sense of entitlement from guests, and hurts the confidence of staff, who don’t feel like they can talk to customers they’re serving as equals.”

Sameer and Yash reason that it’s perhaps the ancient Indian notion of athithi devo bhagwan (‘Guest is God’) that has bred this status imbalance between guests and front of house staff in restaurants. It’s an imbalance they say gets reinforced by traditional hotel management institutes here, which are primarily concerned with creating a pipeline of pliant drones to supply the big hotel chains in the country rather than celebrate the individuality of the people actually responsible for delivering the service.

In the 2000s and early 2010s, when ‘going out to eat’ in India typically meant you were visiting a restaurant housed within a high-end hotel, that type of culture, which rinsed the personality out of service personnel, was par for the course. “It’s silly,” Yash says. “Because Indians are naturally warm people. We are ‘hospitable’ by nature. When someone comes to your house, it doesn’t matter who it is, you’ll offer them water or tea or biscuits. If you were in the business of serving people in India, why wouldn’t you want to lean into that?”

Sameer explained that what restaurants and hotels in India historically used to get wrong is that they confused hospitality as being the outcome of a chemical reaction. “But hospitality is just about treating people in a better way than you want to be treated,” he says. “It starts with involving your service team into the thinking behind the product and the food, and that's what we set out to do.”

Yash would go on to manage a jazz bar in Singapore that was being set up under the Fairmont Group. Sameer would get the opportunity to work directly with Danny Meyer at the Union Square Hospitality Group (USHG), where he would witness firsthand how “respect for your people could actually drive better business outcomes” when it came to nurturing enduring restaurant brands.

Working in some of the world’s most famous kitchens and bars would become an extended education for the two Cornell graduates. They were fortunate to be able to mine these experiences for insights that would become the scaffolding of their vision for Indian dining.

Like, the idea that *how* your meal is served is as important to shaping your impression of a restaurant as *what* is being served.

Or the belief that the personnel *outside* your kitchen have a critical role to play in reinforcing the story of the food you’re cooking *inside* your kitchen.

Or the thought that “you should treat your team in the same way that you would want them to treat your guests”.

These things might seem passé now, because we’ve gotten more accustomed to eating out; because restaurants in India are now regularly founded by entrepreneurs and chefs who’ve spent time in kitchens abroad; and because our minds and palates have become more exposed to culinary nuance courtesy of cooking shows, travel and social media. But a decade ago, this was closer to counterculture than convention.

It seemed, then, that if you were considering starting a new restaurant in India in the mid-2010s, and your intention was to break new ground, an obvious way to differentiate yourself would be to borrow the emerging standards of American hospitality and apply them in an Indian context.

But that kind of cultural translation requires more than just enthusiasm and good intentions. It requires a missionary, a cultural translator of the highest calibre befitting the task at hand. In the case of Sameer and Yash, well before they had even begun to dream up their vision for Hunger Inc, they were fortunate to encounter a kindred spirit who filled in all their culinary gaps, someone who’d been building his own culinary bridge between the United States and India since as far back as 1988.

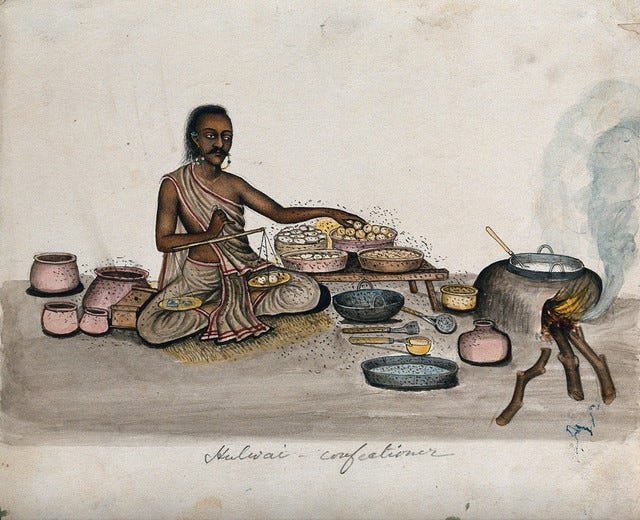

4. Flavorwalla

“Growing up and staying in Bombay from the 1960s through 1980s, good Indian food, as I knew it then, was always regional. Cooked and eaten at home, it was delicious. As a young boy I would wait for my friends to invite me over for a meal…especially those who were from different parts/regions of India—from Maharashtra, Kashmir, Karnataka, Bengal, or Rajasthan. Some of these friends were Catholic, or Hindu, Muslim, Parsi, or Sikh. No matter who they were, or where they came from, there was always amazing food cooked and served at home. My love for food grew from these meals.”

- Floyd Cardoz (Foreward to Tiffin)

Before The Bombay Canteen could exist, before regional Indian food could be considered fashionable in exalted culinary circles, before Indian chefs could be celebrated for innovation rather than tradition, there needed to be Floyd Cardoz.

Growing up in a Catholic household between Mumbai and Goa in the 1960s, Floyd had originally embarked on a career in medicine. Eventually deciding to switch lanes, he was considered an anomaly at the time for choosing the kitchen as his home turf. The 60s and 70s and 80s offered no blueprint for a male chef in India seeking culinary acclaim – no household names, no celebrated figures, no path worn clear by those who'd navigated it before. Cooking was seen as a decidedly blue-collar activity, unassociated with celebrity or creativity in the way it is now. “I left India in 1987, and one of the reasons was that chefs were not getting recognition here then,” he later admitted.

Floyd arrived in America in 1988 via stints at the Institute of Hotel Management in Mumbai and Les Roches International School of Hotel Management in Switzerland. After cutting his teeth at some of the city's 'traditional' Indian restaurants, he rose through the ranks at Lespinasse, one of New York’s most illustrious French institutions, becoming the first person of colour, and first person born and raised in India to lead a prominent fine dining establishment in New York City.

His anointing as the ‘godfather of modern Indian cuisine’ began in 1998, when he partnered with the aforementioned Danny Meyer to set up Tabla, a trailblazing restaurant that forever changed how Americans thought about Indian food.

Tabla was built on a radical notion: that Indian cuisine deserved the same care, attention, and respect as French, Italian, or Japanese food. It wasn't just about dressing up Indian food in ‘fine dining’ garb – it was about challenging the very concept of 'Indian cuisine' as a monolith.

Floyd often argued that bundling the diverse culinary traditions of India under one umbrella was as absurd as grouping French, Italian, Spanish, and German cuisines under the banner of 'European food.' The differences between a Goan fish curry and a Kashmiri rogan josh are more pronounced than between a coq au vin and a beef bourguignon, yet one was treated as a variation on a theme, the other as a distinct expression of regional identity.

“Indians have to tell the story that our cuisine is fucking amazing, and it doesn’t have to be thought of as something that’s pedestrian or cheap or Curry Hill. We want to show you things that we eat here all the time.”

- Floyd Cardoz (via Ugly Delicious on Netflix)

Tabla was a return to the kind of ‘Indian food’ that Floyd knew growing up. This was light, soulful fare prepared by members of his family or cooked in the homes of his friends and neighbours. It had nuance, depth of flavour, and varied widely based on who was cooking it, where they were from, what time of year it was, and what was available in the market that day. Seasonal, regional and fresh. Less ‘Indian food’ than Goan food, Bengali food, Malvani food, Gujarati food, Parsi food, or Sindhi food.

To Floyd, that was what Indian cooking was, not the boring, loveless ‘restaurant cuisine’ that was being served in America at the time. He realised that “those who disliked Indian cuisine were afraid of all the lesser-known and unrecognizable Indian ingredients like pomfret and karela and the murky, greasy sauces. The menus in Indian restaurants never changed and were never seasonal. This made it a cuisine that was stagnant and one they did not want to eat very often.”

As chef and author Suvir Saran summed up beautifully in his tribute to Floyd in 2020, “Tabla gave the much needed bridge between the bastardized goopy-gloppy-greasy and cheap and cheery buffet table cuisine that people assumed was the length and breath of Indian cuisine, and what we are now discovering as the regional and seasonal, light and flavorful, fresh and incredibly nuanced cuisines of the Indian sub-continent.”

Tabla added an entirely new vocabulary to the American culinary lexicon. It expanded what diners thought possible from Indian flavours, beyond the tired, murky ‘Mughlai’ formula that was spammed across most curry-house menus.

Dishes that once seemed exotic – like crispy okra salad, upma with seasonal vegetables, bacon-cheddar kulcha, onion rings with chaat masala, or tamarind-glazed fish – eventually became part of the mainstream restaurant repertoire, even outside of America. Perhaps most significantly, Floyd pioneered the now-commonplace approach of applying Indian spice profiles to pristine local ingredients, erecting a culinary bridge that countless chefs have since crossed.

The thread connecting Floyd's childhood in Bombay and Goa to his groundbreaking work in New York (and eventually back in Mumbai) was a respect for food as a vehicle for cultural and personal expression. In his 2016 cookbook Flavorwalla, he reflected, "My food (like my life) is a fusion of many different cuisines and cultures, with subtle Indian accents."

For Floyd, cooking was never just about technique – it was about memory, emotion, and capturing the joy found in everyday moments. He often spoke of standing on a stool as a nine-year-old to fry eggs for his family's Sunday breakfast, of sneaking into his grandmother's kitchen in Goa to pilfer tamarind and pork sausages, and of wandering Mumbai's seafood markets with his mother to select the freshest catch. "Good food and cooking," he once wrote, "is not only about how a dish tastes or looks on the plate, but how good it makes the cook cooking it and the guest eating it feel."

It was this philosophy – that food should be soulful, joyous, and generous – that would resonate deeply with two young Indian hospitality graduates who, twelve years after Tabla first opened its doors, found themselves in New York with the same vision of what Indian cuisine could become.

5. Homecoming

“…anytime I hear or sense “trendy” (as opposed to “enduring”) as an important aspect of what’s going on, my antennae go up. It all comes down to knowing what you stand for and putting your product in the proper context.”

- Danny Meyer (Setting The Table)

Sameer had first met Floyd while still a student at Cornell. He’d been working on an independent study centred on the most successful restauranteurs in America, and was introduced to the Tabla luminary by one of his professors. “Floyd joked that I should go back to India after graduating. He told me that India was where it was at, and that I shouldn’t waste my time in the US. He said ‘just start something in India and I’ll join you’. I assumed he was just being nice.”

The interaction apparently left an impression on Floyd, because he invited Sameer to join him at Union Square Hospitality Group in late 2011, where he was in the midst of setting up his second restaurant in partnership with Danny Meyer.

Unlike Tabla, North End Grill wasn't focused on Indian cuisine. It was primarily a contemporary American seafood restaurant with a strong focus on wood-fired cooking. Sameer joined the team as a manager. As far as he was concerned, it didn’t matter what was actually being cooked. Getting the chance to learn how to properly run a restaurant from Danny Meyer and Floyd Cardoz was like getting the chance to learn how to properly administer an evil kingdom from Sauron and Saruman.

“It was like Disneyland,” he says. “I saw every aspect of what it takes to set up a successful restaurant, and more importantly how to set one up for the long haul. USHG is over 40 years old and its first restaurant is still at the top of its game. That kind of endurance takes a very different mentality. Opening a restaurant in New York is cutthroat as it is. Plus you have the weight of expectations from guests that expect and demand the best from anything that USHG does. To survive and thrive in that kind of environment takes time, and it boils down to culture.”

USHG represented the capstone to his education in the food business. “I saw how a restaurant had to be treated like a social laboratory, because you get to see the full spectrum of human behaviour. As a server, you have to read the table and read the room. You have to predict what people will need and pay attention for clues on how you can make someone’s experience special. It’s a dance between the front of house and back of house - like theatre. When the restaurant opens it’s curtains up - showtime. I spent only a year and a bit at USHG, but I’d never worked harder in my life until then. That experience directly informed the kind of restaurant I hoped to run someday.”

While Sameer was levelling up at USHG, Yash was on his own eventful journey through the Fairmont ecosystem, moving from Chicago to Singapore, cycling through various operational roles. "I was a jazz bar manager, a poolside manager and a quality assurance manager," he says. His education extended from perfecting the bitter-sweet equilibrium of a negroni to designing systems to keep birds away from eating bircher muesli off a hotel buffet.

Despite the 12-hour time difference and their demanding schedules, Sameer and Yash made a concerted effort to stay in touch. Their conversations often circled back to the possibility of someday bringing their collective experience back to India. They had so far reaped the benefits of learning and making mistakes on someone else’s dime, but were feeling the itch to have more skin in the game themselves.

After one particularly exhausting night of work at USHG, Sameer set that ball in motion, punctuating their usual conversation with a phrase that has signalled the divine moment of conception for scores of entrepreneurial dreams in India - “Kuch karte hain”

6. India Today

“I believe the next step for Indian food, restaurants and chefs is to celebrate India. Look for ingredients from the far reaches of the country. Celebrate the cooking of all regions. Figuring out a way to use ingredients that our forefathers used in everyday cooking will evoke magic.

- Floyd Cardoz (via Chillies and Porridge)

Hunger Inc’s inaugural venture emerged partly as a result of Sameer and Yash looking around at what was happening in the restaurant scene in the United States and Singapore, and partly from observing how standalone restaurant culture was evolving back home in India.

From their perspective, in 2012, restaurants across North America and Asia were experiencing a renaissance of localism. Chefs were turning inward, rediscovering their own culinary heritage rather than chasing international trends. There was an explosion of farmers markets, locally-sourced ingredients, and a newfound appreciation for regional traditions - creole cooking in the American South, BBQ in Texas, hawker cuisine in Singapore, farm-to-table fare in California. Chefs were telling stories of their lives through their food, connecting people to a special place, a time, and a memory.

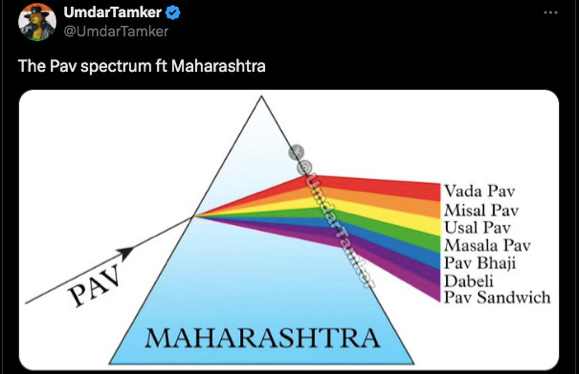

Back in India, standalone restaurant culture was just emerging from the shadows of five-star hotels, but without same introspection. “At the time, if you were going out to a restaurant in India, you either went out for Asian food, or you went out for ‘Continental’ food, where every menu featured the same holy trinity of burgers, pizzas and pastas, regardless of the context,” recalled Yash.

Dining attitudes were different back then too. Compared with today, eating out was more of an occasion than a lifestyle, which meant you mostly went out to eat things you couldn’t get at home. So even if you were going out for ‘Indian food’, it meant you were usually selecting between one of two available options.

“You would either go to a South Indian Udupi-style restaurant where you got your idli and dosa,” Sameer explains. “Or it was North Indian Mughlai-type cuisine - your local Moti Mahal or Copper Chimney, where you knew what your order was going to be even a week before you went. It would be some combination of butter chicken, dal makhani, palak paneer, and naan. And you’d get exactly what you came for. The meal was always delicious and familiar, and you’d walk out happy, stuffed, and ready for bed.”

These kinds of establishments had been around for decades. They had found a winning formula around providing delicious crowd favourites in non-intimidating family-friendly environments, and stuck to it, seeing no reason to fix what wasn’t broken. “But they weren’t the kinds of places you’d go to for a night out, or for a date, or to find an inventive cocktail programme,” says Sameer. This lack of reinvention played a major part in explaining why Indian restaurants had acquired a reputation as “places you would take your parents to”.

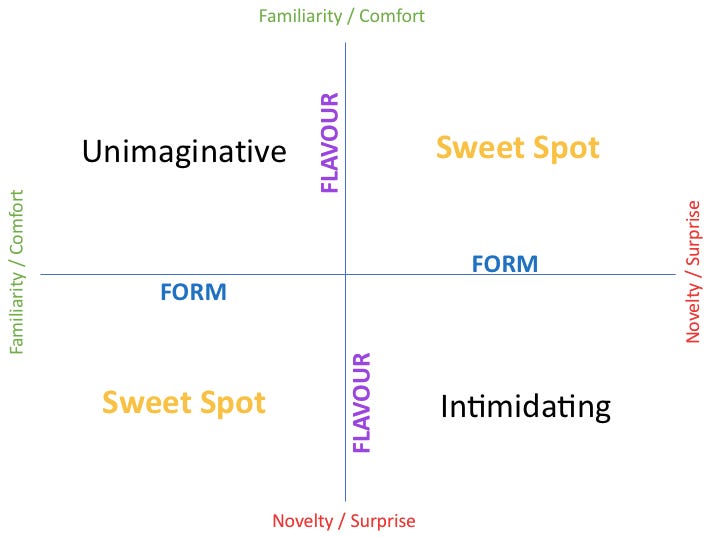

Similar to the epiphany that Floyd had had more than a decade earlier with Tabla, Sameer and Yash felt that there was so much more to Indian cuisine that lay between the Butter-Chicken-and-Dosa axis. There was so much regional variety that hadn’t yet been reimagined or showcased in a contemporary setting. There was no Indian restaurant for “the India of today”.

The duo had noticed that, as Indians became more exposed to sushi, ramen and risotto, we had developed a blindness to the wealth of our own cuisine. We had been trained to think that ‘Indian food’ - a mosaic of 28 different cuisines with spices, flavours and techniques bequeathed by the British, Mughals, Dutch, French, Portuguese, Persians and everyone else who passed through The Golden Road, was somehow not exotic enough to merit a sophisticated restaurant setting.

The gap they identified went beyond just what was on the plate. It extended to the entire *experience*—the ambience, the service style, the beverage program. The duo saw an opportunity to create something that spoke to a new generation of Indian diners. These were the individuals who’d gotten comfortable with travel, who’d been exposed to global restaurant trends, who were looking at food as a form of entertainment, and had yet to experience the same quality of experience enrobed around their own cuisine - not the monochromatic ‘Indian restaurant’ food that the world had come to associate with the Subcontinent, but the seasonal, fresh, nuanced, delicious food that had been thus far mislabelled as ghar ka khana.

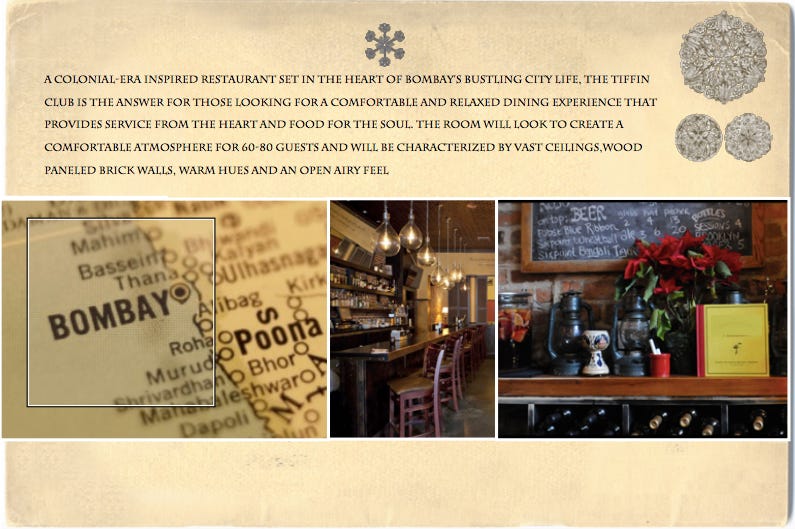

That’s where the idea for Tiffin Club came from.

7. Tiffin Club

In late 2012, Sameer and Yash took the decision to quit their jobs to bet on themselves (and their restaurant idea). Rather than elbowing for room in the crowded restaurant landscapes of America or Singapore, they reasoned that it would be smarter to return to India, to do battle on home turf.

The next big call was to decide which city would be their ideal landing spot. After briefly mulling over options like Bangalore, Delhi and Pune, they zeroed in on Mumbai. “Mumbai has always had a more experimental palette when it comes to food,” says Yash. It helped that both of them had spent the early part of their careers in the city. It was also fitting that Mumbai, India’s pre-eminent melting pot, had always welcomed amalgamation. It had always been appreciative of reinvention. Thus Maximum City was the perfect stage for what they had in mind.

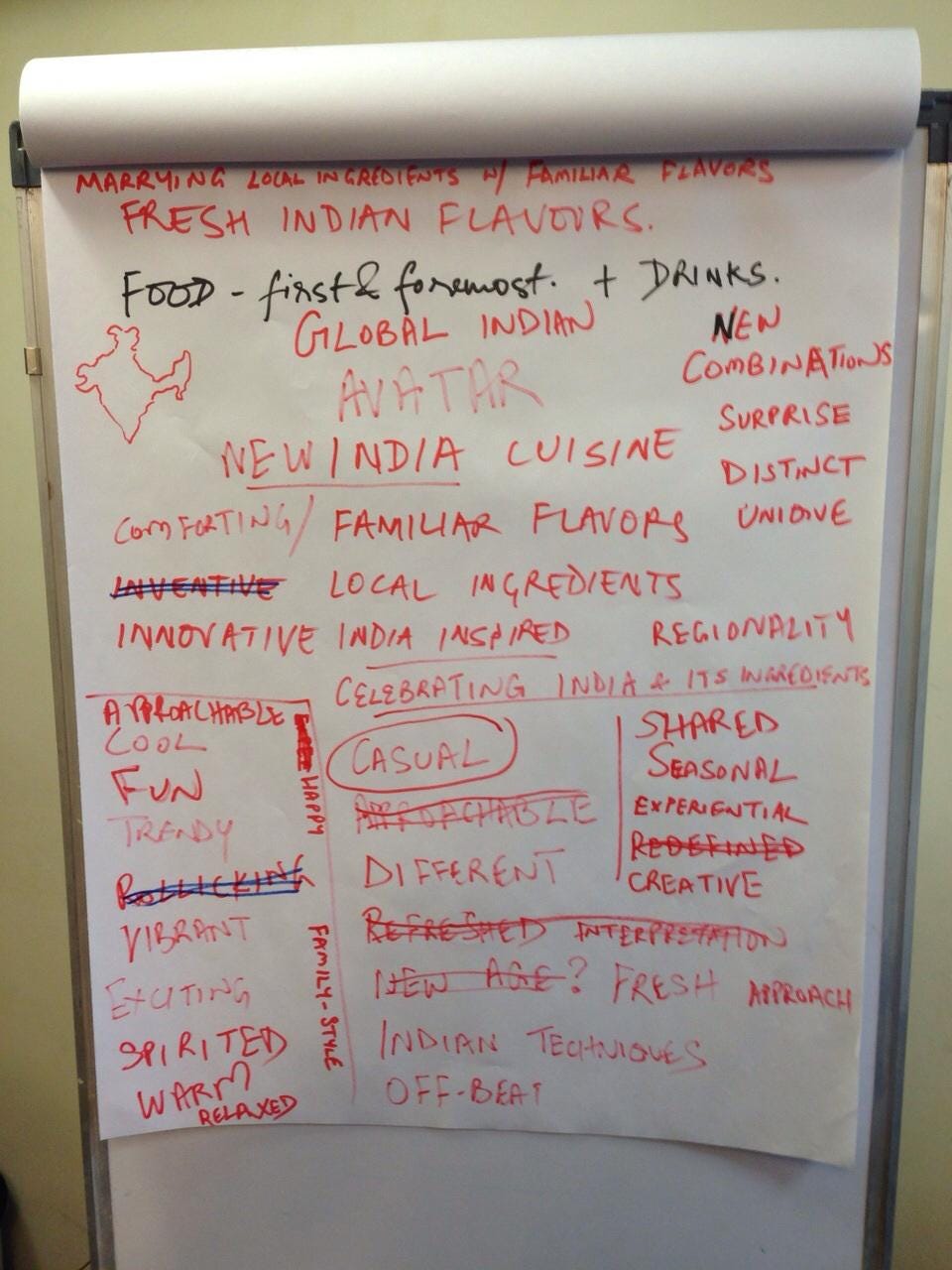

As for what they had in mind? They laid out their thesis in a concept note (one that would go through a few subsequent iterations, but remain mostly true to the original vision).

The name was an extension of this ethos. ‘Tiffin’ was the British term for a light midday meal that had been co-opted to describe the modern Indian ritual of carrying and sharing home-cooked food from stacked metal containers. The ‘Club’ part didn’t have any thing to do with nightclubs. Instead it was a nod to the colonial-era community hubs that dotted India's presidency towns – those membership establishments where people gathered for sports, drinks, conversation, and connection.

‘Tiffin Club’ spoke to the kind of restaurant they wanted to create - one that celebrated India through its food in a casual, fun atmosphere – reimagining traditional recipes using only locally sourced ingredients, with menus changing regularly to reflect what was in season. It would reject the performative stiffness of fine dining – their staff would be encouraged to be themselves, guests could dress however they pleased, and the experience would feel like eating in someone's home. (Their attempt to use the name would ultimately be thwarted, but we’ll get to that later).

The only wrinkle was that neither of them were trained chefs. “We were honest with ourselves,” says Yash. “Both me and Sameer were front of house and operations guys. We needed someone who could make the menu that matched our vision.” Without any connections of their own, they approached Sameer’s old boss Floyd Cardoz for advice. “We presented our idea to Floyd over Zoom to get his feedback,” recalled Sameer. “We told him this is what we’re thinking, and asked if he could connect us with any chefs in India who might want to come onboard.” To their surprise, Floyd volunteered to join them himself.

His leap of faith would steel the would-be restauranteurs with confidence, validating their thesis, and legitimising their efforts. It would also honour an offhand promise Floyd had made to Sameer when the latter was still at Cornell, to join him if he ever decided to start something in India. As to why a chef with his pedigree and stature would agree to join two upstarts with no restaurant experience, Floyd would later attribute it to their enthusiasm, their realness, and their vision that resonated with him. “More importantly,” says Sameer, “we had the balls to ask.”

Floyd came on board as their third partner in 2013, adding “flavour” to their business plan. Having spent over a decade educating Americans on the nuances of Indian cooking, he was able to provide the philosophy and language that grounded their vision. The trio raised around Rs. 1 crore as startup capital, partly from external investors and partly via a loan from Sameer and Yash’s parents. They spent a few months fleshing out their idea over cross-continental Zoom calls. Sameer would move back in early 2013, Yash soon after, where they would kick start their hunt for the right location to bring their vision to life.

8. The Bombay Canteen

It took almost nine months for them to find a home.

For any restauranteur in Mumbai, finding the right commercial real estate at the right price in the city is akin to threading the eye of a needle through a haystack. Given that Hunger Inc were marking their arrival with a novel concept that hadn’t been proven yet, they had to be judicious about where they planted their flag. After scouring for a suitable site in every corner of the city, they found their home on the grounds of an old textile mill that, fittingly and poetically, was in the midst of its own reinvention.

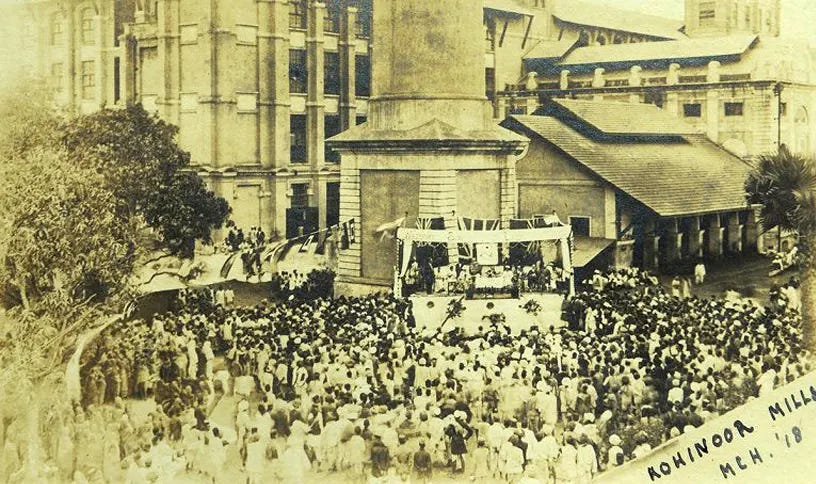

For those not clued in to the city’s history, Mumbai's textile mills were once the economic and social backbone that transformed a fishing village into an industrial powerhouse. In the mid-19th century, as the American Civil War cut off cotton supply to British textile factories, Bombay - with its deep-water harbour and new railway connections to the cotton-growing regions of India - stepped in to fill the void. The city's first cotton mill opened in 1854, and the subsequent mushrooming of mills cemented its status as 'The Manchester of the East'.

The ‘cotton boom’ shaped Mumbai’s identity, attracting waves of migrants from across the country seeking opportunity, thus creating new neighbourhoods, dialects, and cuisines, and establishing the city as India's commercial capital and multicultural hub. The mill owners became the city's new aristocracy, while mill workers sowed a distinct working-class culture into the seams of the city. By the 1980s these mills had outlived their usefulness, and the land was gradually repurposed for luxury apartments, towering high-rises, entertainment venues and office space over the subsequent decades.

When Sameer and Yash stumbled onto the 4000 square-foot husk of an old mill building in the compound of the erstwhile Kamala Mills, it didn’t exactly scream ‘restaurant’.

“At the time, Kamala Mills wasn’t the bustling commercial complex it is now,” explains Yash. “Todi Mills, across the road, was where the action was. There were places like Blue Frog and Cafe Zoe that were already open and doing well there. But the rent was too high for us, so we looked at Kamala Mills, which was like the less sexy step sister. It was a mostly empty compound then. There were no big high rises in the area yet. And the big offices hadn’t started moving in - it was mostly blue collar work spaces. We knew we would have to make the market ourselves, but we saw the potential of the site. It was a big, open space. There were high ceilings, and scope for a lot of natural light. It was a bet on the area too, that there would be enough of a ‘demand circle’ of offices and residences to sustain a lunch and dinner service. Most importantly it fit within our budget for rent [around 12-15% of their forecasted monthly sales].”

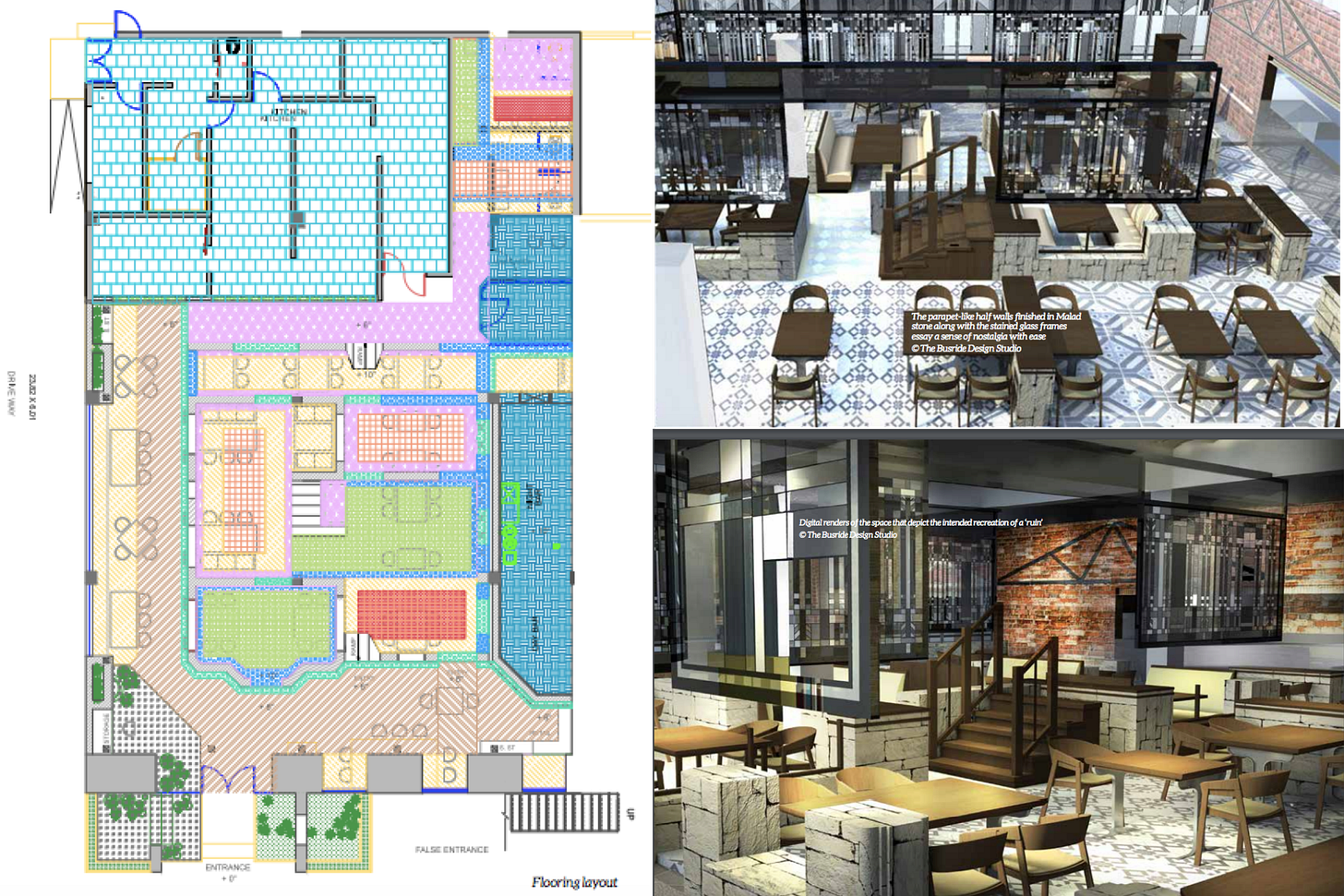

To translate their vision into a physical space, they enlisted Ayaz and Zameer Basrai of The Busride Design Studio, who’ve left their architectural fingerprints on many of India’s prettiest restaurants and cafes. The brief was clear: to create a place that celebrated both the old and new of Bombay through its design—a space that felt both nostalgic and contemporary, similar to their vision for the menu.

The Basrai brothers approached the project with a forensic mindset, sifting through literature on what makes spaces feel inviting. They observed that people naturally gravitate towards walls and windows when entering a large space—because these provide a sense of being anchored, of being safe and grounded. This insight defined their approach.

They conceptualised a space that looked as if an old colonial-era Bombay bungalow had been plucked up by a giant crane, leaving behind memories, materials, and unfinished fragments. The resulting design incorporated ‘Malad’ stone walls rising just three feet from the ground, creating semi-private dining zones; stained glass windows and partitions inspired by Mumbai’s iconic Irani cafés; an assortment of coloured and patterned floor tiles resembling those from an old Bombay mansion; and even a staircase that ended mid-flight, suggesting a history interrupted.

The idea was to create an “incomplete structure”, to give people the feeling of walking amongst the old walls and old rooms of a typical Bombay bungalow.

"We thought it'd be fun to populate a ruin with another ruin," explained Ayaz Basrai. "It's like walking into a large warehouse and stumbling upon the wrecks of an old bungalow inside."

"The clarity in food offerings, the overall city-love, and the leanings towards a nostalgic nod to the 'Best of Bombay' informed the design process profoundly," Ayaz said. The bar was designed with deliberately lopsided shelves displaying an eclectic mix of props, artefacts, frames, and books alongside the liquor bottles.

All of the design fed the overall narrative. Every element told a story, inviting patrons to piece together remnants of a fictional bungalow through clues embedded throughout the space. The structure deliberately juxtaposed colonial Mumbai (the old stone walls) with contemporary Mumbai (via the Art Deco elements in the glass and steel), capturing both tradition and modernity.

Their design ultimately transformed a barren mill space into what felt like the dining room of a colonial-era Bombay home. It would eventually find its true identity as a slightly different type of communal space.

“A few months before we opened there was another restaurant called Tiffin Time that launched in Mumbai, so we had to change our name” recalled Yash. “We wanted to incorporate the word ‘Bombay’, because the restaurant would be a product of its surroundings and its community. And we decided to go with the word ‘Canteen’ because it felt like that was the kind of environment we were hoping to create. Everyone in India has a memory of a canteen - your school canteen, your college canteen, your office canteen. It’s where you would catch up with your friends, chat with your crush or gossip with your colleagues. We wanted to offer that same setting for people - a place where they would feel comfortable visiting on any occasion, a safe space to exchange stories. That’s why we went with the name.”

With a name and space in place, the next big priority was to define what they were going to cook, and more importantly, who would be doing the cooking.

9. Outside In

“I believe a cook becomes great when, and only when, he or she understands where his or her taste buds come from. Understanding their native cuisine gives them an understanding of the nuances of all cuisines.

- Floyd Cardoz (via Chillies and Porridge)

Back in 2014, Floyd was still juggling his restaurant commitments in the US. He planned to divide his time between New York and Mumbai for the opening of The Bombay Canteen (TBC). It meant that Hunger Inc still needed to find someone on the ground to lead the kitchen at TBC. Their search led them to two chefs whose culinary philosophies would set the tone for their decade-long adventure.

The first was Thomas Zacharias. Thomas had fallen in love with food as a kid back in his grandmother’s kitchen in Kerala. He’d seen how people’s faces would light up with happiness as soon as she laid down her food on the table, and become hooked by that “superpower”. After graduating with a degree in hotel management from Manipal, he trained at the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) and worked at the three-Michelin-star restaurant Le Bernardin in New York, before returning to India to helm the kitchen at Olive Bar & Kitchen in Bandra, Mumbai.

While Hunger Inc was beginning its search for a head chef, Thomas had just come off a four-month sabbatical through Europe, where he’d visited France, Spain and Italy for the first time. He had hoped to get better intimated with the European fare he’d been serving up at Olive, and the kind of cuisines that had become his go-to speciality in the initial years of his career. The trip had led to a very different kind of epiphany, courtesy of a meal at the famed Osteria Francescana in Modena, Italy, hailed by many counts as the best restaurant in the world at the time.

Owing to a late cancellation, he was able to snag a seat as a single diner for the three-hour twelve-course experience, setting the scene for a moment that changed the course of his career. At a talk at his alma mater in 2019, he recounted the incident that led to him eventually coming on board at The Bombay Canteen:

…what was interesting about that restaurant is inspite of its fame, the chef still comes out and talks to every single table. And the chef Massimo Bottura came to my table and he started talking about his inspiration and his philosophy. And he said “what I’m trying to do is showcase my own cuisine, and my inspiration was my grandmother”. And at that point everything changed for me. I had an epiphany at that point. And I realised that, how does it make sense for me, an aspiring chef, to be spending all my time, energy, and money focusing on a different cuisine when I had nothing to explore my own? And that’s when everything changed for me.

Thomas had walked out of the restaurant feeling restless, thinking that his work didn’t have a higher purpose. He came back to India and eventually quit his job at Olive, embarking on another food pilgrimage, this one closer to home. This trip would take him across the Subcontinent, covering 18 states over two months to explore the richness of India’s own food traditions, unearthing recipes, flavours and techniques that rivalled anything that Europe could offer. Around this time a headhunter connected him to the Hunger inc team, who were looking for an Executive Chef to run The Bombay Canteen, a new restaurant that wanted to spotlight the vast bounty of India’s culinary terrain. As Thomas recalled - “I was sold in five minutes”.

Thomas came on board as the first Executive Chef and one of the four founding partners of Hunger Inc, along with Sameer, Yash, and Floyd, who served as Culinary Director for the group. Equally important to forging the group’s DNA was Thomas’ sous chef (second in command) at The Bombay Canteen and eventual successor as Executive Chef of the company - Hussain Shahzad.

Hussain would only join the crew a few months after The Bombay Canteen had already opened, but had been on the team’s radar since well before that. Born in a Bohri Muslim household in Chennai, with a father from Mumbai and mother from Patna, Hussain's upbringing was a mishmash of cultures that shaped his fluid approach to cooking: "There are no rules. If it tastes delicious, it belongs."

Like Thomas, Hussain's earliest food memories were shaped by family. They involved sitting by his grandmother on the patla while she rolled out rotis, waiting to be rewarded for sitting patiently with one lathered in gud and ghee. Also like his future kitchen-mate, he’d started his hospitality education at WGSHA in Manipal (a few years Thomas’ junior). After working as a banquet chef at the Trident Hotel in Mumbai, he swapped the suite life for the pressure-cooker kitchen of Eleven Madison Park in New York, working under Chef Daniel Humm to learn what it took to run the kitchen at the best restaurant in the world. The exacting standards and attention to detail meant that “Every night was a World Cup final.”

In 2014, Hussain had made up his mind to leave EMP and return to India (but not before a two week stint working as Roger Federer's personal chef). Through Thomas, Floyd heard about this talented Indian chef looking to come home and saw an opportunity. It would take three separate recruitment attempts before a final ambush at The Bombay Canteen after the restaurant had already opened finally convinced him that their vision of modern Indian cuisine—thoughtful, technique-driven, and deeply respectful of regional traditions—was something he wanted to be part of.

I had the chance to chat with Sameer, Yash and Hussain for this story, and the thing that stood out for me was that aside from Floyd, none of the founding team (or Hussain after) had ever worked in an Indian restaurant before. No one had even cooked Indian food professionally before. On the contrary, all of them had come through the Indian hospitality machine at a time when your self worth as a chef was measured by your mastery over European techniques and flavours - the age of béarnaise, not bhuna.

As it turned out, that clean slate was probably a big part of why the eventual menu at The Bombay Canteen was such a departure from convention. “We had less emotional attachment to traditional recipes,” says Hussain. “We were able to look at the entire landscape of Indian food with curiosity, with humility, without any pre-conceived notions, and allow ourselves to be guided more by flavour profiles, techniques, memories, and ingredients, rather than a futile attempt at chasing ‘authenticity’. If you think about it logically, what was once new and innovative is something we regard as ‘authentic’ today. To us those ‘authentic’ dishes should be used as the starting point for innovation, not the end. And we fully expect that our own creativity today will one day become the inspiration for someone else’s experimentation. That’s the approach we took.”

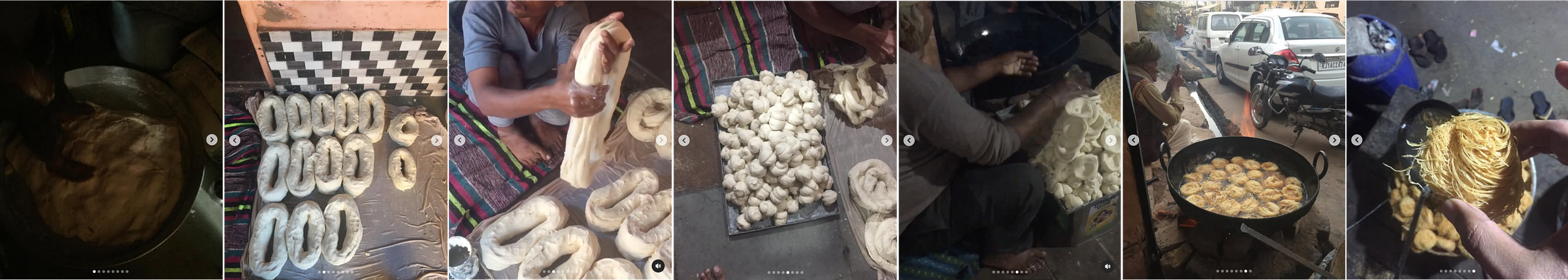

Before opening, the team did what they've continued to do before launching any concept: immersive research. They traveled extensively across India, gathering not just recipes but context. Their approach wasn't to visit established restaurants but to dive into homes, markets, and roadside eateries—places that are still strongholds of our food traditions. What they found was that ‘Indian cuisine’ wasn't one thing but dozens, hundreds of micro-cuisines that varied widely in how they did things.

Each of these local doctrines has its own techniques and flavour principles, influenced as much by religion, caste, wealth and class as much as they are by geographical boundaries. For example, a sambar in a Brahmin household is likely to be made with ghee and without onions and garlic; or consider that in Rajasthan's arid climate, the warrior Rajput caste developed meat-heavy dishes preserved with spices and ghee, while merchant Marwari communities evolved sophisticated vegetarian alternatives using local desert ingredients. The deeper the Hunger Inc team burrowed into Indian cuisine, the more they realised there was no such thing. “It’s why we say that we don’t spotlight Indian cuisines at The Bombay Canteen but the ‘cuisines of India’,” says Chef Hussain.

Unsurprisingly, when TBC opened in February 2015, the commitment to showcasing the full wealth of India’s food made it quickly apparent that there hadn’t been an Indian restaurant like it before.

10. “It’s a good day to Bombay”

The Bombay Canteen opened its doors to the public on 11th February 2015.

The day before, on 10th February 2015, Arvind Kejriwal of the Aam Aadmi Party was elected Chief Minister of Delhi in a landslide victory that marked the start of a new political era in India’s national capital.

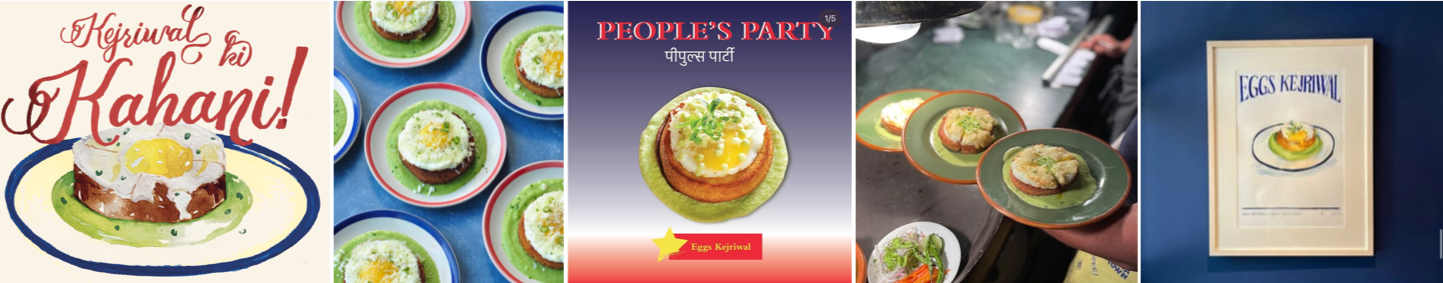

I imagine after reading that last sentence you’re wondering what this random bit of trivia has to do with the crew at Hunger Inc?? As it turned out, Mr. Kejriwal’s victory would lend the gift of inspiration for a dish that would become one of TBC’s most cherished and iconic creations, conceived on the restaurant’s very first day of operations.

“Thomas [Zacharias] had come up with this terrific green chilli coconut chutney based on his grandmother’s recipe that we couldn’t figure out what to do with,” recalled Sameer. “We had this brioche bread leftover from another dish, and the night before opening, some of the team decided to combine this bread and chutney with eggs and cheese to make our own version of the Eggs Kejriwal. It was so good that we decided to put this on the menu as a special on Day 1. We got reviewed and written about that day so everyone who came in afterwards kept asking for it.”

“Now, If you grew up in Mumbai, you probably know the origin story of the Eggs Kejriwal at Willingdon Club. This gentleman named Devi Prasad Kejriwal was a vegetarian at home, and wanted to hide the fact that he used to come to the club to get his fix of fried eggs from other guests. So he used to ask the servers to disguise the eggs with a layer of cheese, green chillies and chutney. If you knew that story, that’s why you ordered the dish. But for everyone that didn’t, they thought it was funny that we were paying homage to Arvind Kejriwal’s victory. The name continues to strike a chord with people even today, and you’ll have a table of 20 coming in just to order 20 Kejriwals each. Why? Because at its core it’s just a yummy, comforting chilli cheese toast. And it all started with some spare ingredients and a pop cultural moment coming together at the right time.”

TBC’s Eggs Kejriwal - simple, delicious, tongue-in-cheek-y, with just the right dash of culinary flair and a fun story to boot. It was The Bombay Canteen in a nutshell.

The mythology surrounding this instantly-signature dish added an extra ‘z’ to the buzz that had been brewing ahead of the restaurant’s launch. Not that it needed any extra juice. TBC could already count on the considerable hype that had surrounded the homecoming of Floyd Cardoz, almost thirty years after he’d left the city for foreign shores to find the right appreciation for his culinary gifts. Hype can often be a double-edged sword in the restaurant business, but in the case of Hunger Inc and TBC, what kept them even-keeled was the fact that the only pre-existing image they really had to live upto was the one that had been germinating in their heads for the past 24 months.

“When people first walked into Bombay Canteen, they saw these Malad stone walls, this Art Deco inspired glasswork, colourful retro posters, a beautiful bar and cocktail programme, staff in T-shirts with ‘Bro’ written on them. It might seem a bit clichéd now but 7-8 years ago none of it conformed to any pre-existing image of an Indian restaurant,” says Yash.

Similar to what Floyd had done with Tabla in 1998, TBC didn’t offer a caricature of India. Instead, it presented a vivid portrait of a very different profile of the country that hadn’t yet been expressed in a restaurant setting - a lighter side that that didn’t take itself so seriously.

Instead of table lamps and Taj Mahal’s, the team dabbled extensively in nostalgia to stir up the kinds of warm, fuzzy memories that people associated with their favourite Canteens. Every detail was defined working backwards from the sense of homely comfort they wanted their guests to feel when they walked in.

This meant repurposing old Rooh Afza bottles as water jugs, the same way that Indian households used to do in the 70s, 80s and 90s; or using old-school hand-bound account registers as menus; or taking their branding cues from retro posters ripped out of old magazines; or sending around trays of snacks and chai in the evenings the way you would if you had guests visiting your home. It even extended to their delivery packaging, which was designed to resemble a traditional cloth-based potli, that Indian families would use to carry their food while travelling (this one could even double as a reusable tablecloth).

A lot of the credit for the personality of TBC is owed to Avinash and Pritha Thadani, the husband and wife duo that founded Please See, one of India’s foremost design and branding agencies. If Hunger Inc is a family, then Pritha and Avinash are the type of cousins that are around so much that your mom instinctively just puts out a couple of extra plates for dinner every night. Originally recruited by the Hunger Inc team to help with logo and menu design for TBC, the Please See duo have become a “mirror” to everything the team does, contributing to some of the most pivotal ideas and initiatives of the company over their decade long journey.

Pritha summed up the ethos of the team in the early days, telling me that “They wanted start a conversation about India in a softer setting.”

Where TBC broke with convention in India was in entrusting its front-of-house staff to carry that conversation. “We call it ‘Hospitality First’,” says Yash. “It’s about treating our team the way we want them to treat our guests. It’s about building their confidence over time so they can speak to our customers on an equal footing, and help tell the story of the restaurant. We want our servers to be able to tell you their opinions on dishes, and not just recite ingredients.”

The only way to do that was to have their service staff sit at the same table as the rest of the team, involved in pre-serving briefings the way it was done in the West, trying and tasting all the food that the restaurant would be serving so they could come up with their own impressions firsthand. Clad in various playful, pun-friendly T-shirts in the early days (inspired by Batman, Star Wars, and whatever else was top of pop culture at the time), the idea was to use a combination of explicit and implicit cues to slowly break the ingrained socioeconomic barriers that typically colour the interactions between diners at servers at high-end restaurants in India.

As to what was being served? Floyd's mandate to the team was “to teach people to eat the way we used to eat—and make it accessible, affordable and fun. Don’t do things that will cost people an arm and a leg because they’re not going to want to come and eat with us.”

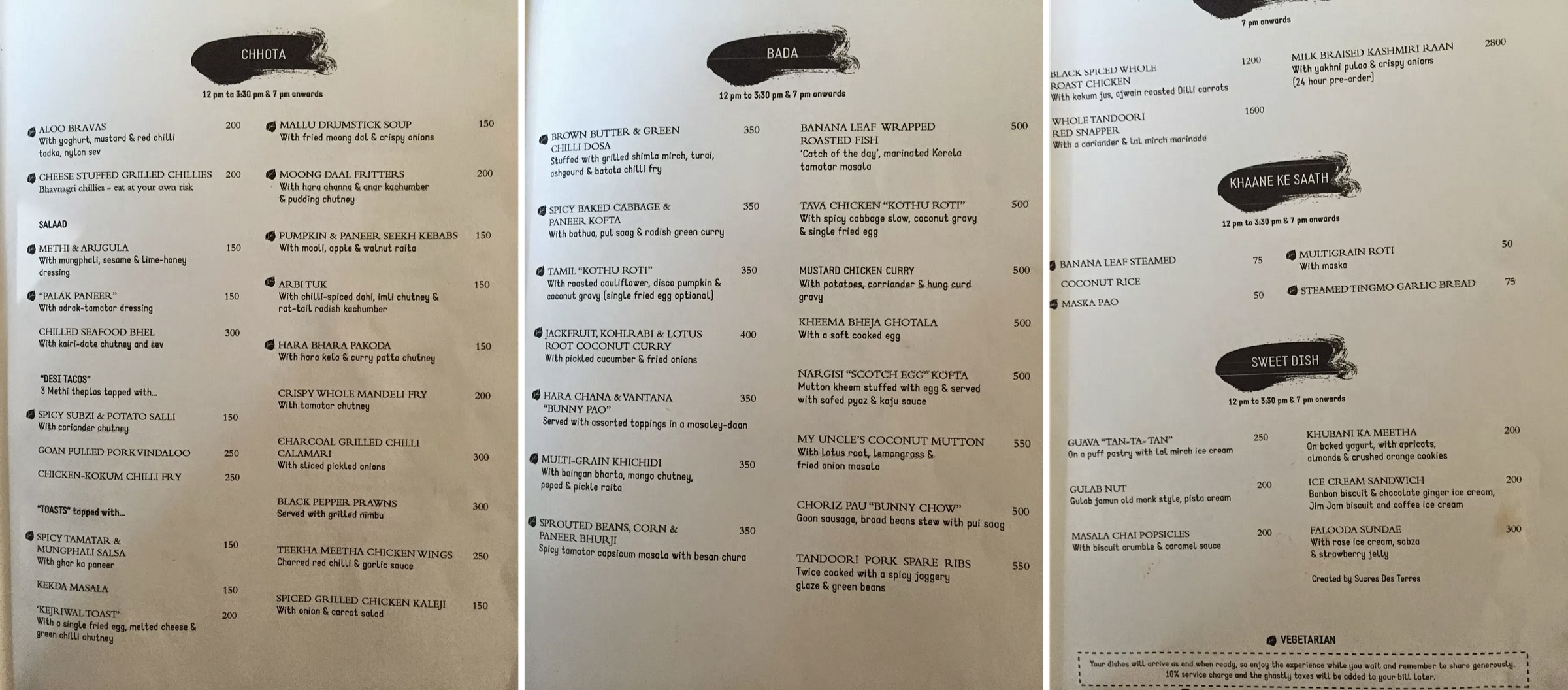

The first iteration of the menu was focused on spotlighting regional dishes that were not typically found on ‘premium’ restaurant menus. These were dishes inspired by their travels across India, by their childhoods, by their families, and by the city.

The goal was to demonstrate that lesser-known ingredients, dishes and micro-cuisines could not only be as interesting, but as delicious as the usual ‘Indian’ food that restaurant-goers were used to sampling. That point had to be continually massaged in, even in the face of the occasional critique.

“I remember we had a customer who came in and said ‘you have a tandoor, you have chicken, why can’t you give me chicken tikka?’, but we had to stick to our guns and be clear about what we were and what we weren’t. We realised you can’t be everything for everyone, and that’s okay,” says Sameer. The team will also freely admit that it took time to get the vegetarians on their side. “The four of us original partners were all good carnivores, and a lot of our early veg dishes were just stripped down versions of our non vegetarian food. That’s not the case now.”

Even in the early months, for every occasional person that said ‘why would I go to a restaurant and pay money to eat things like lauki, arbi, mandeli, and poi saag, when I can get the same thing at home?’, there were scores more that beamed with pride seeing that dishes from their homes and hometowns were cool enough to make it onto a restaurant menu.

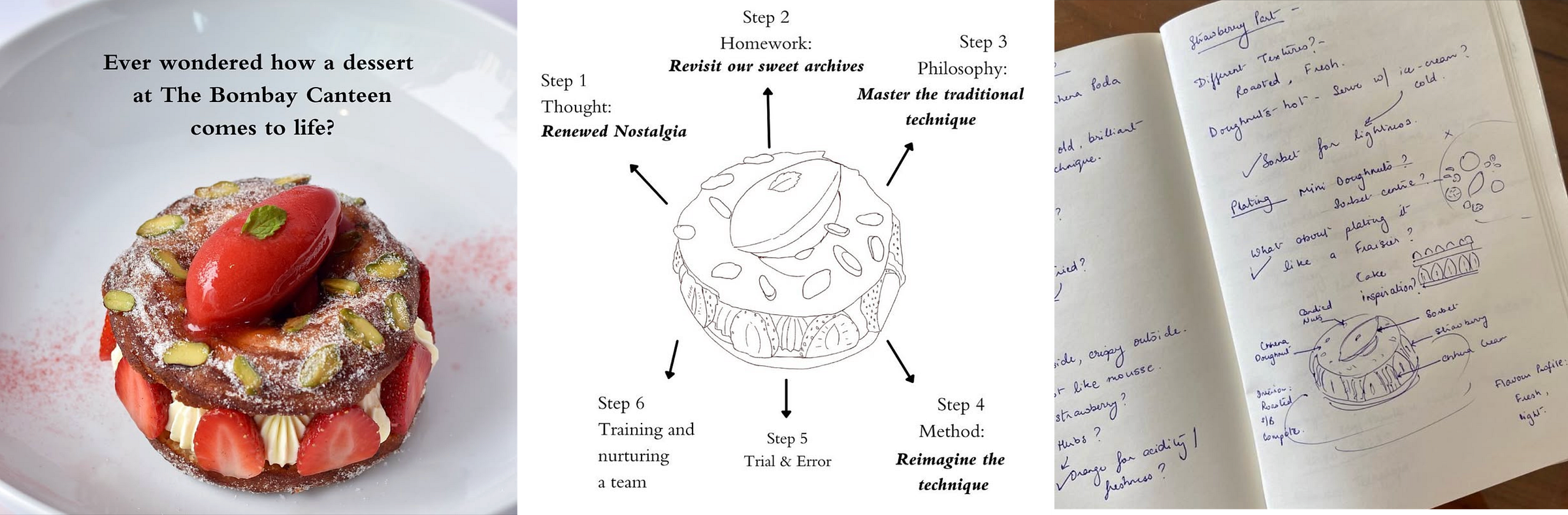

In what has become a running theme with any of their restaurants tackling cuisines of the Subcontinent, there is a lot of thought that goes into this presentation. It’s never innovation for the sake of innovation, reinvention for the sake of reinvention, or representation for the sake of representation. Instead they always ask themselves whether are adding something new and substantive to the dialogue about Indian food.

I didn’t get to chat with Chef Thomas Zacharias (who led the kitchen at TBC as Executive Chef for its first five years), but he summed up his approach to showcasing unheralded regional cuisines on a podcast last year that I thought was particularly insightful:

…the questions I would ask when I came across dishes that inspired me on my travels is that:

Has this food been served in restaurants in mainstream cities before?

Am I doing justice by bringing these dishes to the forefront? Are they lesser known dishes? Is there a point to be made here?

Do I need to alter it in some way to make it accessible for people in cities or can they exist on their own?

…but the first thing that I would always do is recreate the original dish the way it is before innovating, because if you cant do that then you’re not really holding on to the integrity of those original inspirations.

In other words, there was always a sense of purpose to what they were doing in the kitchen. That sense of rootedness in something real, is a big part of why TBC has been able to thrive for over a decade (as of this time of writing). “By the mid 2010s there were lots of new ‘modern Indian’ and ‘Indian fusion’ restaurants that were beginning to emerge,” recalls Yash. “Most of these places were trying to ape this silly trend of molecular gastronomy. It was liquid nitrogen this, dehydrated that, it was all smoke and mirrors. There was no heart in any of it, which is why none of those places are still around. What we were trying to do was different.”