Wings Over India: Manufacturing Our Aviation Future

A Spotlight On...Puss-Moths, Maharajas, and the clarion call for India to get busy building airplanes

Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 518 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece.

Incidentally 518 is the number of times we’ve watched this low budget gif of the last South African wicket from the 2025 Women’s Cricket World Cup Final -

Congratulations to the ladies for getting the job done - hit the applause button below to show your support🇮🇳🏆

Tigerfeathers is presented by…Fuzz AI

Fuzz AI is the intelligence layer for modern investors, purpose-built for India’s financial landscape.

It’s the newest product out of the lab at Raise Financial Services, adding to a roster that includes Dhan, Upsurge and Filter Coffee - each designed to help Indian investors navigate the country’s public markets.

Unlike generic AI tools that are trained to summarise data, Fuzz is programmed to verify. Every answer is backed by visible, traceable public sources.

Built for serious investors, analysts, and finance professionals, Fuzz understands the intricacies of Indian regulations, policies, and market quirks that global tools miss.

It’s like having your own personal research analyst, one that understands the rhythms of India’s financial landscape.

What makes Fuzz different:

Verified insights with sources and citations

Deep research mode by default

India-centric financial datasets

Specialized agents for filings, sentiment, and quant data

50K+ investment professionals are already on the waitlist. Fuzz is currently in beta, but you can register for free access here👇

And if you’re interested in partnering with us on a future edition of Tigerfeathers, hit us up on Twitter/LinkedIn or by replying to this email. With that, let’s get to it.

There’s a term we’ve been using in conversations for much of this year to describe what feels like a new epoch in India’s startup odyssey: The Age of Audacity™️

Over the past 18ish months, as many of the software stalwarts of the past decade graduate to their next phase as public companies, there’s been a shift in the tectonic plates of Indian tech. Amidst the consumer-facing fervour for vertical quick commerce apps, ceremonial-grade matcha, AI companions, and short-form video platforms, we’ve seen an emergence of a new archetype of Indian founder.

This cohort skews younger, more brazen, more willing to peer above the shards of a shattered glass ceiling in search of dusty domains that would have been dismissed as entrepreneurial dead ends in generations prior.

Space. Biotech. Aviation. Robotics. Defence. Climate. Manufacturing. Energy.

In short, the world of atoms, not bits.

The ‘why’ propelling this wave requires a more nuanced answer (and likely its own essay), but more pertinent is the ‘why not?’ that’s infected the ambitions of pioneers in this Age of Audacity (T-shirts coming soon). In fact, we’ve been fortunate to feature a handful of these ‘deep tech’ stories over the past year - stories like that of Pixxel, PopVax, and Airbound.

Anyway, this week, for the third edition of The Tigerfeathers Spotlight Series (i.e. our guest writer programme), we’re going to hear from someone currently surfing this new wave. Or to be more accurate, someone who’s very recently taken flight…

Into The Spotlight

Please join us in welcoming Khushi Mittal to the podium.

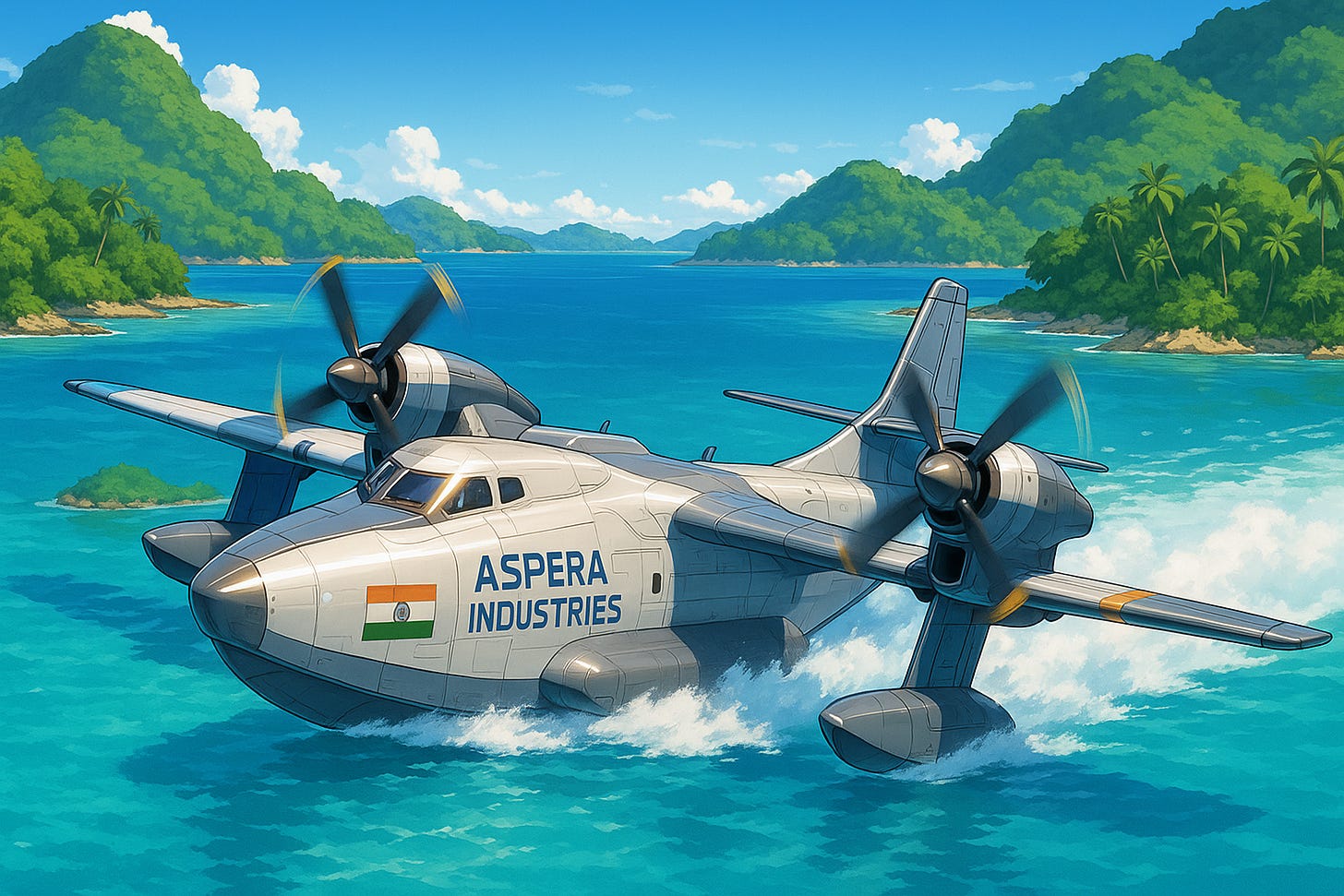

Khushi is the Founder and CEO at Aspera Industries, where she and her team are building autonomous, amphibious airplanes capable of taking off and landing both on water and flat land.

Aspera’s planes are designed to operate from makeshift water runways and short landing strips, targeting cargo routes between warehouses and ports that currently rely on slow boat transfers or costly conventional air freight. The company aims to commence its operations with island nations and coastal shipping lanes across Southeast Asia before expanding to land.

Khushi’s long term goal is to build the world’s first autonomous airliner - built for the world from India - capable of being our country’s answer to Boeing and Airbus.

That goal is made all the more impressive considering she dropped out of the University of Alberta midway through her undergraduate second year, where she was on course to finish with a degree in Physics and Computer Science. At the time, she had burrowed deep into the AI rabbit hole, but was emboldened to move back to India (and Bangalore) by a timely $8000 grant from Emergent Ventures in 2024, to chase her childhood dream of “doing something in aviation”.

It’s not easy for someone to just saunter out of college and set up a highly technical new venture, so Khushi counts on a number of “wanderings” over the past four years that illuminated her path to Aspera in early 2025. To get to know her better, these adventures, in her own words, include:

Aspera closed a $750K pre-seed round earlier this year led by our friends at Inuka Capital along with Antler India and Boundless VC, along with angel cheques from Awais Ahmed (Pixxel), Paras Chopra (Lossfunk), Sameer Brij Verma (Northpoint), Soumitra Sharma, and Aaryaman Vir Shah (one half of Tigerfeathers).

So what’s on the runway today?

Like many of the people we enjoy learning from most in the Indian startup ecosystem, Khushi is a prolific writer. She’s married her engineering and humanities sensibilities in features for Contrary Research and Asimov Press, along with her own bubbly Substack (check out her recent piece on ‘Leeches and the Legitimizing of Folk-Medicine’ if you’re a fan of strong opening sentences).

Her piece this week on Tigerfeathers is true to form. It’s about her first love - aviation. It tells the story of India and airplanes - and why we don’t build them today (but why we should). It’s part historical vignette, part black-and-white industry overview, and part personal reflection on why she’s doing what she’s doing.

If you’re on the look out for inspiration to chase down your own dream, this essay is a pretty good start. It features a Rubik’s cube, maharajas, jet engines, and an ashtray made by Salvador Dali.

We hope you enjoy, we hope you learn something, and we hope you extend Khushi the same patience and appreciation you do for us.

With that said, lets get on with it.

1. Before You Can Fly, You Must Dream

Brazil Defies The Odds

It was the morning of 26th October, 1968, and the air on the makeshift strip at São José dos Campos hung thick with humidity. A handful of engineers, some in smart coats and others in oil-stained overalls, hauled an unfamiliar white airframe out of its hangar and watched as the pilot climbed into his seat.

At the edge of the tarmac stood Ozires Silva, a young Brazilian Air Force officer turned aeronautical engineer. He had spent years shepherding this improbable machine from the pages of his sketchbook to something that finally resembled a flight-ready airplane. Now all he could do was bite his nails and wait as the pilot flicked the switches to bring the turboprops alive.

A thump. Then silence.

Silva exhaled sharply. Not today. Not after everything. Under his breath he muttered, “Come on, you son of a bitch. Fly.”

And then came a cough, a sputter, and a shiver through the fuselage. The twin Pratt & Whitney PT6 engines finally woke up, the propellers biting into the morning air.

Moments later, the aircraft surged forward, shrugged off the runway, and climbed.

This is how the EMB-110 Bandeirante took its maiden voyage as the first ever aircraft designed and built in Brazil. But it did not come easy. As Renato Oliveira, a pioneer in aviation preservation and history, later wrote:

Brazil’s industrial elite believed aircraft manufacturing was too risky, too expensive, and best left to the Americans or Europeans. Financial institutions refused to invest. Friends and colleagues urged Silva to abandon the project. But he did not retreat. With conviction and diplomatic skill, Silva took his case to the federal government. In 1969, his efforts bore fruit.

A year after the successful demonstration of the Bandeirante (Portuguese for ‘pioneer’), the Brazilian government formally created Embraer, a state-owned aerospace firm. They installed Silva as the company’s president, and gave him a clear mandate: to build aircraft that could help military and commercial customers traverse the vast internal distances that stretch the length and breadth of Brazil.

Under Silva’s stewardship, the company went further than they imagined. Not only did they build several aircraft that faithfully performed within Brazil, they also became renowned suppliers for the rest of the world. By the 1990s, Embraer would be privatized; by the 2000s, it would be the third-largest aircraft manufacturer in the world, a position it still enjoys today.

Today, Embraer is valued as a $12 billion dollar NYSE-listed global exporter, generating nearly $5 billion in annual revenue, employing 23,000 people, and building everything from light attack aircraft to the commercial E-Jet family that flies routes for carriers like British Airways, JetBlue, and KLM.

It did not just build Brazil’s engineering and commercial credentials, it also built Brazil’s confidence in itself.

Europe Enters The Fray

Two years after that first muddy takeoff in São José dos Campos, a different conversation was happening across the Atlantic.

In 1970, ministers and engineers from France, Germany, the UK, and Spain gathered to discuss a problem that had been growing for a decade: Europe had ceded the skies to America.

The global commercial aviation market was dominated by the US firms Boeing and McDonnell Douglas; if the status quo persisted, Europe risked becoming a permanent customer, rather than a competitor. The Americans were flying passengers on 707s and DC-8s. The Europeans were buying them.

The answer, the Europeans decided, was not to sit around and mope. It was to build, and to build big. The group decided to launch a multilateral joint venture that would aim to roll out world class passenger aircraft. They named the initiative Airbus.

“I wanted to use all the available talents and capacities to their utmost without worrying about the colour of the flag or what language was spoken.”

- Roger Béteille, Airbus founding father and chief engineer

This was no small feat. Four nations with different languages, regulations, and industrial traditions would somehow coordinate to build a single aircraft. Within two years - an astonishing sprint for an industry accustomed to decade-long development cycles - engineers in Toulouse rolled out the Airbus A300, the world’s first twin-engine wide-body airliner.

On 28 October 1972, barely four years after the Brazilian Bandeirante’s modest opening salvo, the A300 roared into the sky, heralding Europe’s return as an aviation power.

Roger Béteille, the project’s technical director and one of Airbus’s founding minds, later reflected:

“We had to bring something more. ‘Something more’ was daring to use advanced technology wherever it could bring economic results. We had to take more risks of failure than the established manufacturers.”

In other words, they had to be scrappy and operate like a startup. They couldn’t compete on legacy or scale, so they competed on innovation and risk tolerance. It’s hard to deny that those risks paid off.

Today, Airbus is the clear global leader in commercial aviation.

It delivers almost 900 new aircraft every year, with an order backlog of 10,000. It generates €70 billion in revenue, €5 billion in profits, and sits pretty with a market cap of over €160 billion, all while employing more than 150,000 people.

But over and above just the numbers, Airbus is special because it represents one of Europe’s most successful experiments in political coordination, industrial planning, and long-range engineering ambition.

China Flexes Its Muscles

Fast-forward to the early 2000s.

Boeing, Airbus, and Embraer jets were the pride of their patron nations and the envy of everyone else. But there was a rising power that had awakened from its long slumber and cast a hungry eye towards the skies; China.

With its mighty industrial base, large and technically skilled population, and visionary political will, China had all the ingredients to take on the reigning kings of aviation. The question was not whether China could build aircraft - it was when.

And so, in 2008, in the wake of the Beijing Olympics that had announced China’s arrival on the world stage, China established the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China, also known as COMAC.

It had one goal: to build a homegrown commercial aviation industry that could rival, and eventually eclipse, all other competitors.

The idea was not to license production lines or merely assemble the final technology the way they had done for some Western firms like Apple. Instead, COMAC was set up with the ambition of designing and manufacturing their airplanes in-house, and becoming the go-to provider for Chinese airlines, and eventually, the world.

The journey wasn’t the smoothest at first, but it certainly produced results. The first domestically produced aircraft entered active service in 2016, in the form of the the Comac C909.

The eventual ramp up of this aircraft was similarly slow, but it steadily increased year-on-year. By 2023, the C909 had already carried over 10 million passengers on routes between Shanghai, Beijing, Chengdu, and Shenzhen.

Today, it has ferried 25 million passengers all over the expanse of China. There are more than 160 C909s in active service, most of them flying for the “Big Three” airlines: Air China, China Eastern, and China Southern. Several hundred more are in production as we speak, commissioned by virtually all of China’s domestic airlines.

The C909 has also begun to hit the export market. It has found customers in Lao Airlines (Laos), TransNusa (Indonesia), and Vietjet (Vietnam), though its key market remains China’s vast domestic aviation sector.

As we speak, work is underway on a Comac C929 model, a twin-aisle jet airliner that would compete with the Airbus A350 or Boeing 777 to service long-haul routes. The early planes are imperfect, but so were those of Airbus, Embraer, and Boeing when they started.

This is nothing new: every aviation power begins with a prototype that barely gets off the ground. What matters most is tenacity and ambition.

And China’s ambition is clear for all to see: become the world’s third great commercial aircraft manufacturer, and eventually, number one.

So what is the point here?

The point of all of these stories is to illustrate that every great aviation success begins with a dream, and with belief.

The odds are never in your favour when you want to build something as hard as an aircraft, but if you sit around waiting for perfect conditions, you have zero shot.

Embraer began with a small team on a humid runway and built one of Brazil’s greatest export engines despite widespread scepticism.

Airbus began as a political experiment and became Europe’s industrial crown jewel.

China began with no meaningful aircraft industry and is now mass-producing commercial jets for the world’s largest aviation market.

None of these journeys were easy. They were constrained by capital shortages, supply-chain gaps, geopolitical pressures, and technological catch-up. But the pioneers persisted. And their persistence led to great progress in the those countries.

Which leads to the obvious question: when will it be India’s turn?

2. India’s Tryst With Aviation

JRD Tata Kicks Off The Story

Nothing worthwhile is ever achieved without deep thought and hard work. No achievement in material things is truly worthwhile until it serves the needs of the country.

The quote above from the legendary JRD Tata is one that I often reflect on, especially when thinking about the history of planes in this country.

This may come as a surprise to some people, but India does have a rich national aerospace heritage: one that predates Independence, ISRO, and almost every modern industrial effort we celebrate today. And like so many of India’s great institutions, the story began with the Tatas.

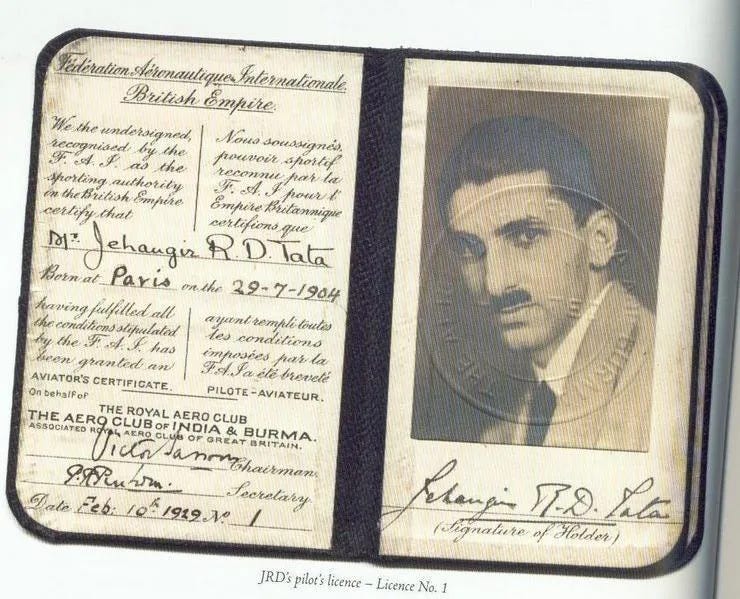

The youngest of the Tata clan, Jehangir Ratan Dadabhoy (JRD) Tata, had caught the flying bug early. Born in Paris and educated across Europe, JRD earned his commercial pilot’s license in 1929—becoming the first Indian to do so.

Flying wasn’t a hobby for him, it was an obsession. So when the Imperial Government of India announced it would contract private operators to carry airmail, JRD saw his opening. He convinced his cousin, Sir Dorabji Tata, to let him bid on behalf of Tata Sons.

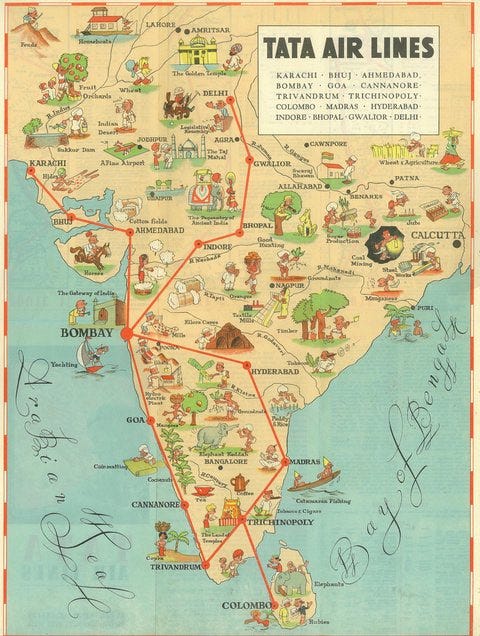

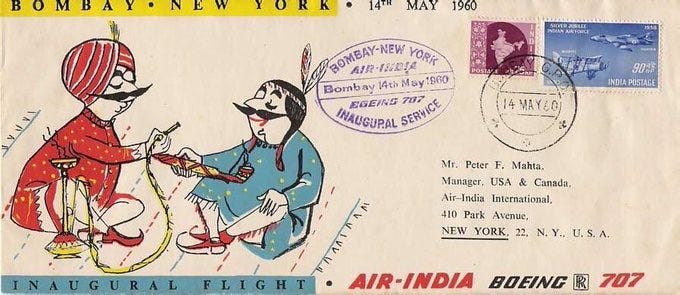

Competing against British firms with far more experience, the Tatas won the contract in 1932. The service would connect Karachi, Ahmedabad, and Bombay - three critical nodes of commerce in British India. The terms were strict: weekly service, weather permitting, with penalties for delays. But JRD didn’t see obstacles. He saw history in the making. JRD, just 28 years old at the time, also insisted on piloting the inaugural flight himself.

And so in October 1932, at a dusty airstrip in Karachi, Mr. Tata sat alone in a tiny de Havilland Puss Moth (still the greatest model name in aviation history), carrying 55 kilograms of mail and a vision far ahead of his times. There was no air traffic control, no proper airports, and no navigation systems. Just a vast, indifferent sky and a privately funded belief that India could one day master the air.

Within a year, Tata Airlines was operating scheduled airmail services across Bombay, Ahmedabad, Karachi, and Madras.

By the 1940s, the airline had evolved from a mail carrier into a passenger service, operating routes that connected India’s major commercial centres. The operation was earning the state’s trust and proving that Indian enterprise could manage complex, safety-critical infrastructure, all before the Indian state itself existed.

In the midst of World War II, while the British Raj was struggling to maintain control and India’s independence movement was reaching fever pitch, JRD’s airline kept flying. It ferried British officials, Indian businessmen, and crucial wartime supplies. The service was so reliable that even the colonial administration came to depend on it.

Then, in 1946, on the eve of independence, the company was formally renamed Air India. More than a rebranding, it was a statement. India, the nation, did not yet exist on any map. But Air India, the airline, was already soaring above it, carrying the name of a country that would be born just one year later.

In Parallel: Walchand Hirachand and HAL

Around the same time, another Indian industrialist was harboring his own aviation ambitions.

Seth Walchand Hirachand was already a legend in Indian business circles, having set up businesses such as Hindustan Construction Corp and the Scindia Steam Navigation Company, India’s first homegrown shipping firm. Hirachand believed deeply in swadeshi industrial self-reliance, and he saw aviation as the next frontier.

In 1940, while traveling from Honolulu to Hong Kong, Hirachand found himself seated next to a gregarious American named William Douglas Pawley.

Pawley was an aviation entrepreneur who worked for the American manufacturing company Curtiss-Wright and had already helped China establish aircraft assembly lines during Chiang Kai-shek’s rule. As the two men talked over the Pacific, Walchand outlined his vision: India needed its own aircraft manufacturing capability, and he wanted Pawley’s help to build it.

By the time they landed, Pawley was sold on the idea.

What happened next was a masterclass in Indian entrepreneurial hustle. Within months, Hirachand had secured land in Bangalore and funding from the Maharaja of Mysore. The location was strategic—Bangalore offered conditions well-suited for aircraft manufacturing and testing.

By December 1940, Hindustan Aircraft Limited (which would later become HAL) was formally incorporated as India’s first aircraft manufacturing company, with Pawley as Managing Director and Curtiss-Wright taking a 48% stake.

Shortly afterwards, in July 1941, the factory delivered its first product: a two-seat Harlow trainer, an American-designed model that was nonetheless the first aircraft manufactured in India.

The factory hummed with activity. Indian workers learned to rivet aluminium, assemble control systems, and test engines. Engineers studied aeronautical drawings. The dream of indigenous aircraft manufacturing seemed within reach.

But then the British noticed what was happening.

World War II was in full swing, and the colonial government was desperate for any industrial capacity it could commandeer. Recognizing HAL’s technical capabilities, the British colonial government quickly jumped in. They nationalized the firm in 1942, and diverted its focus from entrepreneurial aviation to licensed military production.

The entrepreneurial dream died almost as soon as it was born. Instead of developing indigenous designs, HAL became an assembly line for British and American military aircraft.

The British calculus was simple: they needed the factory’s output, but they certainly didn’t need Indians learning to design and build their own aircraft. The last thing they needed during wartime was an airplane manufacturing company owned and controlled by Indians.

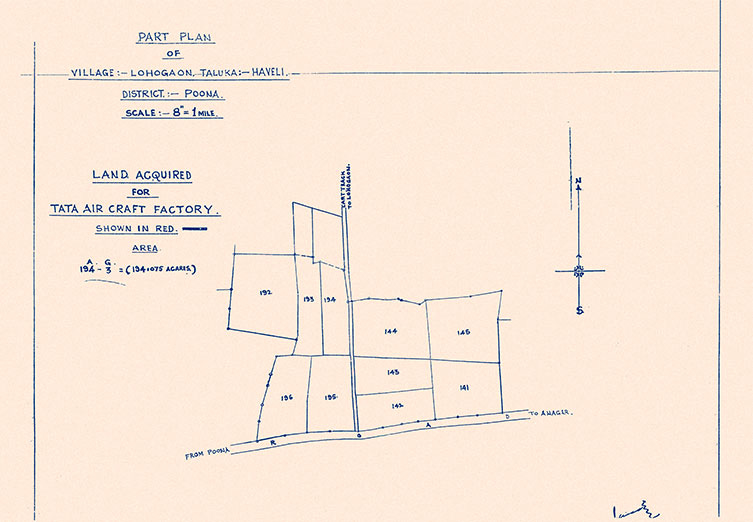

JRD Tata watched this unfold with frustration. He had been pushing for the same opportunity—to manufacture aircraft, not just operate them. In March 1942, even as HAL was being nationalized, he floated a new company called Tata Aircraft with the explicit goal of manufacturing planes in India. His plan was to build the De Havilland Mosquito, a twin-engine wooden fighter-bomber that was bombing Berlin, right here in Pune.

“My devotion to aviation was not only to the airline but to aviation and aeroplanes,” JRD later recalled. “So when the war came along, we decided to offer to build up an aircraft industry that would be useful after the war. Since metal aeroplanes needed a lot of metallurgical materials we couldn’t import easily, we decided to offer to build the Mosquito. It was made of wood and could go extremely fast.”

The British Government said yes. Land was acquired in Pune. A factory was being built. But then, in a cruel twist, the British cancelled the order and asked them to switch to Invasion Gliders instead. When that proved impractical, that too was cancelled. What remained was a contract to assemble, maintain, and repair aircraft—not to design or build them. At its peak, Tata Aircraft employed over 5,000 people and serviced hundreds of aircraft and engines for the war effort. But they never built a single plane of their own design.

This wasn’t the first time that the Tatas’ manufacturing stars refused to align. Over a decade earlier, in the 1920s, Sir Dorabji Tata had rejected a collaboration offer from Holt Thomas—a pioneer of commercial aviation in the UK—to set up an air transport company and aircraft manufacturing facility in India. The Tatas, at that time, felt too occupied with other ventures.

As it turned out, by 1952, Tata Aircraft went into voluntary liquidation. A year earlier, Defence Minister Baldev Singh had offered JRD the chairmanship of Hindustan Aircraft Limited—the same company Walchand Hirachand had founded and the British had nationalized. JRD declined, citing conflicts of interest, but joined the board and served until 1961. He watched HAL grow into one of India’s largest enterprises, building fighters and helicopters under license. But it never became what either man had dreamed: a company that designed and built Indian commercial aircraft for the world. JRD’s ambitions to manufacture aircraft—not just operate them—remained unfulfilled.

And thus, India’s earliest dreams of making planes were clipped before they could take flight—not by technical impossibility, but by colonial design.

Independence, Nationalisation, Opulence, And Decline

After Independence, the trend of stymying entrepreneurial energy in the aviation sector did not abate. If anything, it accelerated.

In 1953, under the Air Corporations Act, the newly formed Indian government nationalised Air India and Indian Airlines. The logic was straightforward: aviation was too strategically important to leave in private hands. But the execution was devastating. While JRD remained chairman of the company he had created, operational control shifted to bureaucrats with little interest in building an engineering powerhouse. Aviation became an instrument of statecraft and soft power, not a domain for industrial ambition.

JRD would later reflect bitterly on this period. As journalist Vir Sanghvi noted, Air India was never just “an enterprise” to JRD—it was “a beloved child.” Watching bureaucrats take control must have felt like losing custody.

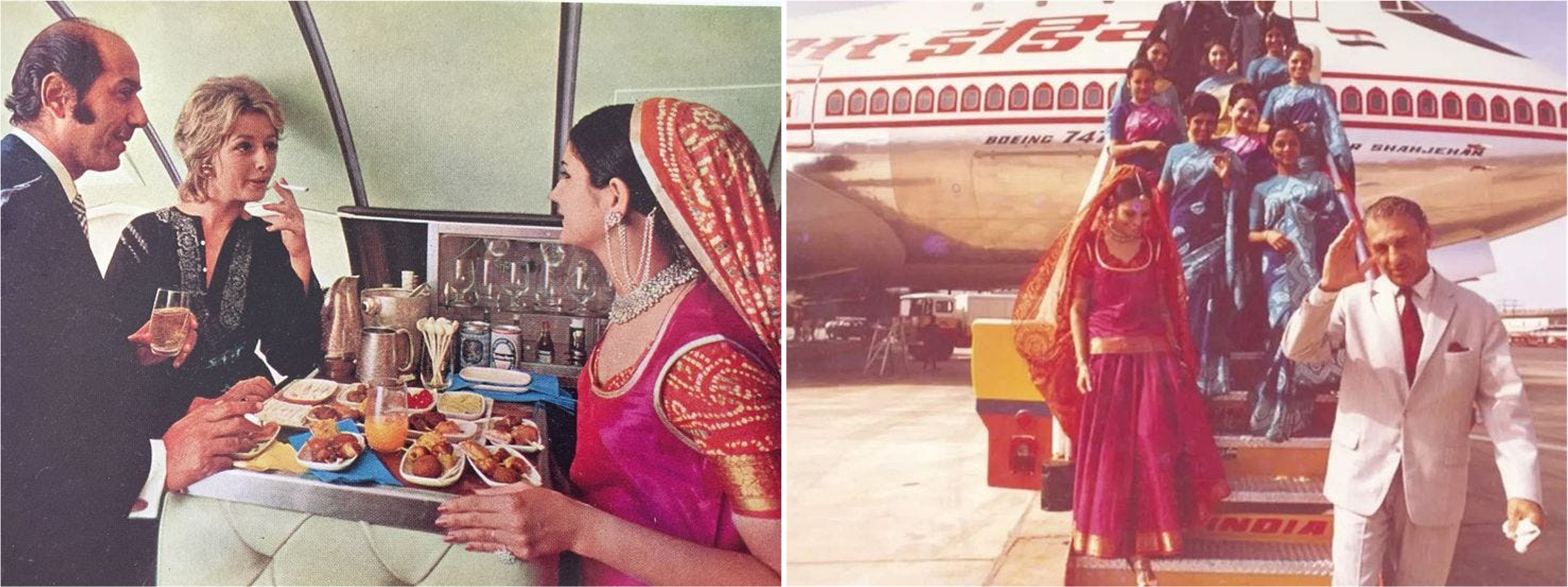

For a brief period, the cracks didn’t show. Air India achieved fame as one of the world’s most glamorous and creative airlines, reputed for their classy service and unique flight experiences. The airline became so legendary for its punctuality that people in Geneva could reportedly set their watches to the time at which the Air India flight flew over the city. The carrier flew international routes with panache, hired multilingual cabin crew trained in hospitality, and turned every flight into a cultural experience.

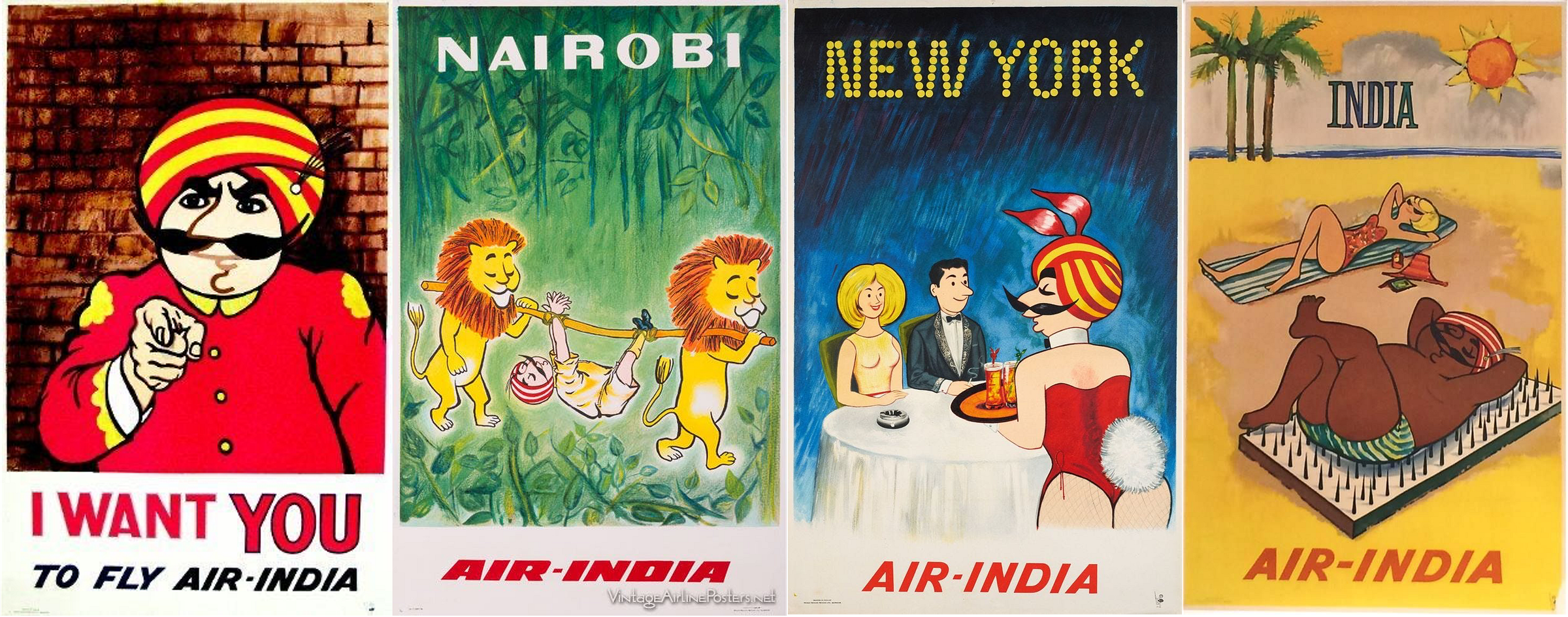

There is perhaps no greater anecdote that punctuates the flamboyance of our national airline during this period than the time when Air India commissioned none other than Salvador Dalí to design a set of ashtrays for 500 of their first-class passengers. Dalí, who was never one for convention, delivered 500 porcelain ashtrays featuring a surrealist design inspired by his painting Swans Reflecting Elephants. In return, he asked for a live baby elephant as payment, which Air India promptly sourced from Bangalore and shipped to his Spanish estate.

In addition to the fabulous service, Air India also became renowned for their cheeky and memorable artistic sensibilities. The portly, jolly Maharajah mascot —created by commercial artist Umesh Rao and designer Bobby Kooka (also Air India’s Commercial Director) — became an icon of Indian service standards and personality.

It was no wonder then that so many high-profile public figures proudly flew Air India when visiting the Subcontinent.

But glamour and good service are not the same as capability in engineering.

Salvador Dalí’s ashtrays didn’t change the fact that every Air India plane was built abroad. Although we could serve customers well, we were not advancing our technology and ability to build better planes.

Meanwhile, HAL remained stuck in its post-nationalization groove. Despite HAL’s accomplishments in the military domain - assembling Soviet MiGs, building indigenous trainers, and co-developing fighter jets - it never became a commercial Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) that built serious aircraft of its own design. Its business model was license production and military contracts, not commercial innovation.

And so it came to pass that India remained a nation that runs airlines but never builds airplanes.

As the years wore on, JRD Tata and Walchand Hirachand passed away and control of India’s aviation stalwarts became increasingly bureaucratic and bereft of entrepreneurial spirit. The founders were gone. The dreamers were replaced by administrators.

Eventually, the lustre that Air India once enjoyed began to dim. By the 1990s, the airline was burdened with debt, bloated payrolls, and aging aircraft. The state-run airline fell behind nimble global competitors who were able to modernize and adapt to the times. What had once been JRD’s “beloved child” became a cautionary tale of how bureaucracy can suffocate even the most promising enterprises.

1991: The Commercial Aviation Market Reawakens

Then, in 1991, came liberalisation.

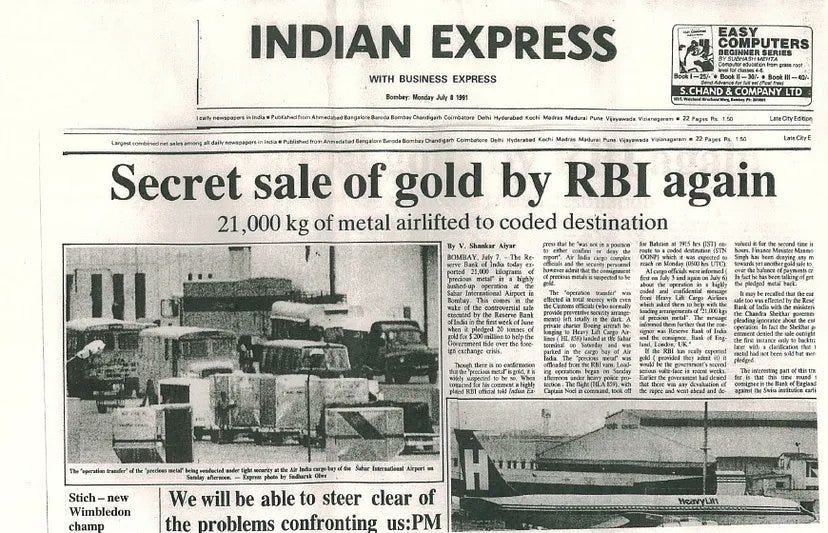

India was in crisis. The country had nearly run out of foreign exchange reserves, forcing the government to airlift 67 tonnes of gold to the Bank of England as collateral for an emergency loan. It was a humiliating moment that forced a reckoning: the socialist economic model had failed.

The socialist forces that had shackled the Indian economy for so long finally gave way, and entrepreneurs were allowed to start companies in industries of their own choosing. As Finance Minister Manmohan Singh, in his famous Budget Speech in July 1991, said, quoting Victor Hugo: “No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come.”

He meant that Independent India was ready to open the doors to a capitalist future, encouraging its entrepreneurs to take bold strides into sectors that had so far been the exclusive domain of the ponderous Indian State.

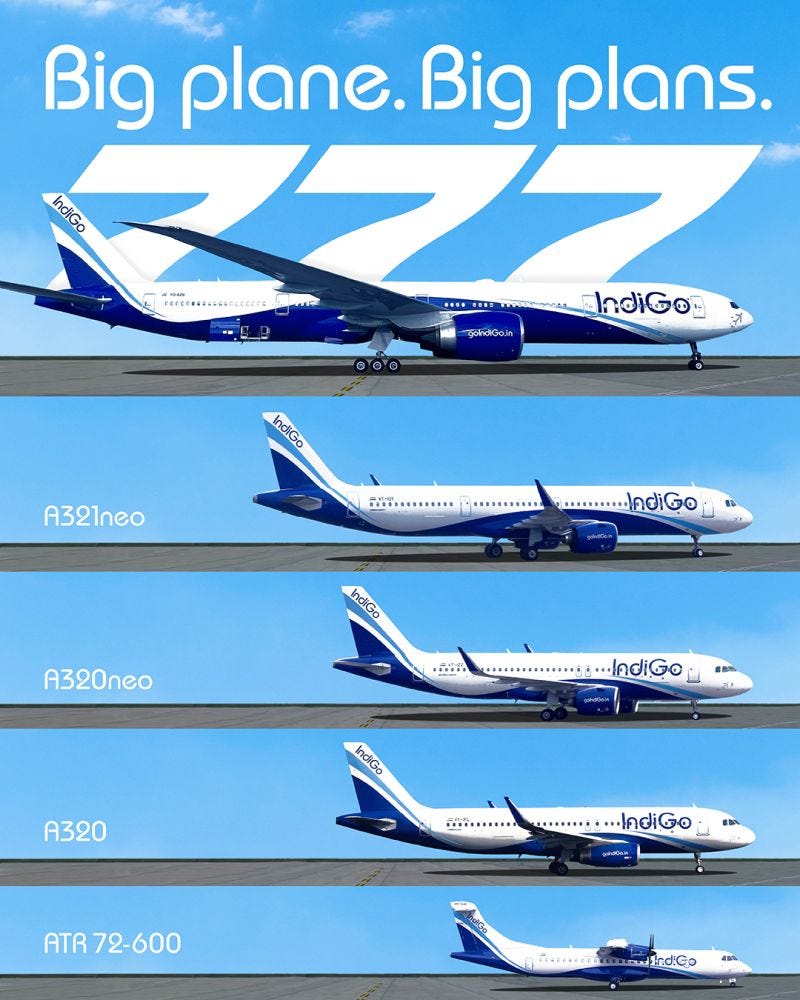

One industry whose time had clearly come was aviation. The monopoly held by state-run carriers was dismantled. Several private airlines sprung up as capitalist energy sought to compete with the aging Air India: companies like Jet Airways, Air Sahara, SpiceJet, Kingfisher, and IndiGo came out swinging and rejuvenated the aviation landscape.

Jet Airways, founded by Naresh Goyal in 1993, brought international standards to domestic flying. Kingfisher, backed by liquor baron Vijay Mallya, turned flights into five-star experiences. IndiGo pioneered the low-cost carrier model with ruthless operational efficiency.

This competition brought efficiency, reliability, and scale. Ticket prices fell. Routes multiplied. Flying, which had once been the preserve of the wealthy and the bureaucratic elite, became accessible to India’s growing middle class. Air travel in the country began to swell.

The transformation was staggering. Jumping ahead to 2025, India has now grown to become the world’s third largest aviation market, ferrying hundreds of millions of passengers every year. In 2024 alone, Indian airlines carried over 150 million domestic passengers, more than the entire population of Russia.

To service this demand, our airlines are amongst the most active buyers of aircraft in the world. In 2023, IndiGo placed an order for 500 planes from Airbus, which was the single largest order in aviation history at the time.

Not to be outdone, Air India placed its own order of 470 aircraft, taking the total number of planes ordered by Indian airlines that year to over a thousand. These were more than just purchases, they were bets on India’s economic ascent, signals to the world that Indian aviation had arrived.

Speaking of the new Air India, it would be remiss not to mention that in a moment of historical symmetry, Air India has returned to the Tata Group, completing an 89-year loop. In January 2022, the airline JRD Tata had founded in 1932 and lost to nationalization in 1953 finally came home.

“Dear guests, this is your captain speaking... welcome aboard this historic flight, which marks a special event. Today, Air India officially becomes a part of the Tata Group again, after seven decades,” Captain Varun Khandelwal announced to passengers on Air India flight AI-665 travelling from Delhi to Mumbai.

But while on the surface this feels like a triumphal return, the fundamental truth underneath has not changed.

We Fly, But We Do Not Build

Despite our massive market, engineering talent, and rich history, we still do not build commercial aircraft.

We operate them, rent them, and import them. But we do not make them.

When IndiGo takes delivery of a new A320neo at Toulouse, Indian pilots fly it home, Indian engineers maintain it, and Indian crew serve passengers on it. But the aircraft itself, from fuselage to flight deck, was designed, engineered, and assembled in Europe.

This is chastening because despite being the world’s third-largest aviation market, we contribute almost nothing to the global aerospace supply chain beyond low-value component manufacturing and assembly work.

The economics aren’t anything to sniff at. Between 2023 and 2024, Indian airlines ordered nearly 1,000 aircraft worth over $100 billion. That’s more than the GDP of countries like Sri Lanka or Kenya, flowing out to Airbus, Boeing, and their suppliers.

The high-margin design work, the advanced manufacturing, the intellectual property, the skilled aerospace jobs—all of it happens in Toulouse, Hamburg, Seattle, and Montreal. None of it happens in Bangalore, Pune, or Hyderabad.

We’ve built world-class airlines. We’ve created efficient airports. We’ve trained thousands of pilots and engineers. We’ve mastered the art of operating aircraft in one of the world’s most challenging aviation environments which features dense airspace, extreme weather, and massive scale.

But we haven’t built a single commercial aircraft that anyone outside India would buy.

For a nation of our size, ambition, and capability, accepting this status quo is simply not enough.

JRD Tata didn’t fly that first mail route in 1932 so that, a century later, India would still be buying planes from foreigners. Walchand Hirachand didn’t fight to establish Hindustan Aircraft so that we’d remain perpetual customers rather than creators.

If we want a legacy in the global aerospace industry that is worthy of JRD Tata and Walchand Hirachand, then we must build.

Not just fly, but build.

3. The Case For Building Aircraft

Why, you may ask, should this be a national priority?

Every nation need not produce every good; indeed, economic theory suggests that countries should focus their energies on those industries in which they have a competitive advantage.

If everybody in the world tried to make their own advanced computer chips, we would burn through a lot of money only to produce a lot of substandard computer chips.

But while this is all true, it misses the point. There is no one single economic reason that we should build aircraft. There are political, financial and cultural reasons, which while powerful on their own, compound on the others to form a national case that is overwhelming.

Here they are.

A. It Builds Domestic Talent, Capability, and National Confidence

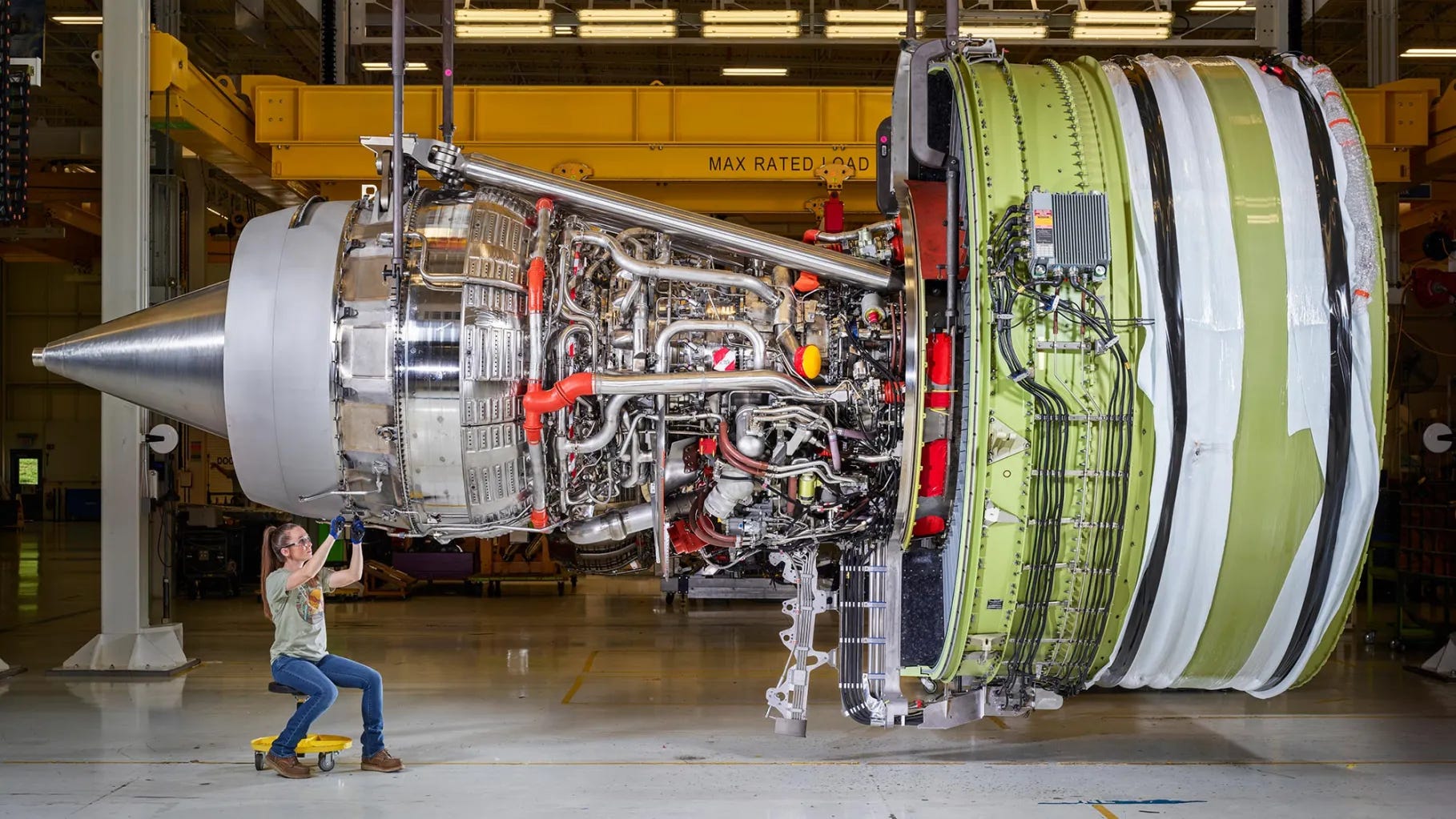

Aircraft manufacturing is the Mount Everest of engineering.

To build even a modest regional aircraft, you need deep strength across aerodynamics, composites, precision machining, avionics, propulsion, systems integration, safety certification, and industrial supply-chain management. Modern aircraft are extraordinarily complex machines requiring the coordination of vast supplier networks and the mastery of multiple engineering disciplines simultaneously.

Every country that has attempted this seriously has found that aviation instantly upgrades the skill base of the entire nation.

When Brazil launched Embraer, the country had limited aerospace capability. Over time, the program created a sophisticated aerospace workforce, established technical institutes, and built supplier networks that hadn’t existed before. The benefits extended far beyond aviation.

This capability then becomes a force multiplier in other domains.

The same engineers who learn to build wings go on to build drones, rockets, satellites, robots, high-performance materials, advanced electronics, and next-generation manufacturing ecosystems. Aerospace expertise transfers naturally to other advanced manufacturing sectors.

When you build a plane, you don’t just create a plane. You create a culture and country capable of building hard things.

B. It Confers Strategic And Defence Resilience

Right now, India is almost entirely dependent on Airbus and Boeing for commercial aviation.

If, for some reason - whether that be geopolitics, export controls, industrial bottlenecks, or simple prioritization - Airbus and Boeing decide they cannot supply India at the scale we need, we have no fallback.

Consider what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic: global aircraft deliveries ground to a halt. Airlines that had ordered planes found themselves waiting years longer than planned. Supply chains seized up. Now imagine that scenario during a geopolitical crisis, with India cut off from access to new aircraft precisely when we need them most.

We are one supply-chain choke away from national vulnerability.

A country like ours, with our 1.4 billion people, should not be captive to the production scheduling of a few foreign firms. India already learned this lesson painfully in other sectors. During the 1965 and 1971 wars, Western nations imposed arms embargoes that left Indian forces scrambling. We’ve spent decades building domestic defense capabilities precisely to avoid such dependence. Why should civil aviation be any different?

By building our own aircraft and supplier ecosystems, we can create strategic resilience that insulates us from geopolitical volatility.

Moreover, every improvement in civil aircraft manufacturing directly strengthens our defence sector.

The technologies are nearly identical. Things like aerostructures, advanced materials, simulation systems, and high-precision manufacturing all spill over into military aircraft, drones, and next-gen defence technologies. A factory that can build a commercial airliner’s fuselage can also build a military transport’s fuselage. Engineers who design efficient wings for passenger jets can design wings for fighter aircraft. The supply chains are fungible.

This is exactly what has happened in Brazil, Israel, Sweden, Europe, and the US. Embraer builds both regional jets and military trainers. Saab produces commercial aircraft alongside its Gripen fighter jets. Boeing’s commercial and defense divisions share suppliers, technologies, and talent.

It’s time we had our own seat at the table.

C. It Generates Exports, Soft Power, And Domestic Profit Pools

One of the main reasons we liberalized our economy in 1991 was because we were running low on foreign reserves. By June 1991, India’s forex reserves had dwindled to barely $1 billion, enough to cover just two weeks of imports. The nation was effectively bankrupt.

This happened because we did not have much to offer the world in terms of exports, but we still relied on the import of critical goods like petroleum and capital equipment.

Consequently, our stockpile of foreign currency used to place orders with foreign counterparties reduced until we had no bargaining power left.

Those 67 tonnes of India’s gold reserves that were airlifted to the Bank of England as collateral remain a humiliating episode that still haunts the national memory.

Thankfully, the situation is much better today. India has forex reserves of around $700 billion, and a more equitable balance of trade than in 1991. But we are still net importers, with a trade deficit of some $300-400 billion dollars every year.

One of the reasons we are in this position is because we have to buy a lot of our key equipment from foreign markets. Such as planes.

Like I said, we import the planes, engines, avionics, and even the high-end maintenance and repair work. Our aviation boom is, unwittingly, a subsidy for foreign manufacturers.

Building even a modest share of domestic manufacturing would redirect billions of dollars of these profits back into Indian factories, engineers, suppliers, exports, and jobs.

Moreover, it would boost our balance-of-trade by giving us the ability to export goods and services.

Look at what happened with Brazil. Embraer now generates over $4 billion in annual revenue, with roughly 80% coming from exports. The company doesn’t just sell planes—it provides decades of aftermarket support, training, and engineering services. That’s recurring foreign currency flowing into Brazil year after year.

This would not only shore up our national exchequer and give us financial benefits, it would also grant us tremendous soft power in the global arena.

Countries that fly your aircraft also buy your spare parts, train their pilots on your systems, invite your engineers to workshops, read your manuals, and literally trust you with the lives of their passengers. In other words, they respect you.

When an Embraer E-Jet lands at London Heathrow or JFK, it’s a rolling advertisement for Brazilian engineering. When a Japanese airline sends pilots to São Paulo for training, Brazil isn’t just providing a service, it’s building relationships, credibility, and influence.

Thus, a strong aviation export capability would be an invaluable lever of Indian statecraft and relationship building.

D. It Reduces the Cost of Air Travel, Boosting the Domestic Economy

Consider what happens when you build aircraft domestically, even at small scale.

Right now, when an IndiGo A320 needs a critical part replaced, that component often ships from Toulouse or Hamburg. The airline waits days, sometimes weeks. The plane sits idle. Revenue evaporates.

But if that same part were manufactured in Pune or Bangalore? It arrives the next morning. Lead times collapse from weeks to days, servicing becomes local and responsive, and supply chain cycles that once crawled across continents now sprint across state lines.

This isn’t just about faster repairs. When you build locally, competitive pressure erupts. Prices fall. Innovation accelerates.

And when airline operating costs fall, something beautiful happens downstream: tickets get cheaper.

The Bangalore-Guwahati route that once cost ₹8,000 drops to ₹4,500. Suddenly, it’s not just business travellers; it’s students visiting home, small traders exploring new markets, and families taking their first flight.

More routes to smaller cities also spring up. Airlines start serving Tier-2 and Tier-3 towns that were never economically viable before.

This gives cities like Coimbatore, Indore, and Visakhapatnam the chance to become regional hubs, spawning hotels, logistics networks, and entirely new service economies around their airports.

This is not theory. This is exactly what happened in Brazil after Embraer scaled up. Regional connectivity exploded. Towns that were 12-hour bus rides from São Paulo became 90-minute flights. Agriculture, tourism, and manufacturing all accelerated because people and goods could finally move.

The principle is simple: when you make it cheaper and easier to move things around, you don’t just improve existing markets. You unlock markets that simply didn’t exist before.

A farmer in Nashik can now fly her organic produce to Delhi in two hours instead of trucking it for twelve enters a market she couldn’t touch yesterday. A manufacturer in Surat can receive precision components from Bangalore overnight instead of waiting a week..

When connectivity becomes cheap, every other sector accelerates.

E. It Inspires the Next Generation of Indian Builders

Although the other reasons for building manufacturing capability are very valid, this might be the most important of them all.

Imagine what it does to a young child in school to know that the plane flying over her head was built right here in India, by men and women just like her.

It shatters a glass ceiling and expands the universe of possibilities that she is able to imagine. That girl will subconsciously dream bigger now and reach for loftier goals.

When American children in the 1960s watched the Apollo missions, they didn’t just see rockets, they saw what was possible. Enrolment in engineering programs surged. An entire generation grew up believing they could build impossible things. Many of them did.

When Chinese students today see COMAC aircraft taking off from Beijing, they see proof that their country builds world-class technology. When Brazilian children see Embraer jets at their local airport, they see a national champion that exports to the world.

What do Indian children see? Airbus and Boeing logos. Every single commercial aircraft in Indian skies carries a foreign brand. The implicit message: aviation is something other countries do.

This is an intangible asset that cannot be valued in the same way as trade deficits and operating costs.

Who knows what beautiful things will get created downstream by children who were inspired in this manner?

It is also my humble submission that aviation has a cultural effect that other forms of engineering cannot match. There is something about a fast, loud, gleaming plane soaring through the sky that is special.

It makes engineering feel magical and heroic.

It is no surprise that countries with credible aerospace ecosystems also exhibit strong student capabilities in STEM, high-end technical institutions, and advanced research and innovation. The United States, France, Germany, Brazil, and China have all invested heavily in aerospace and they all enjoy world-class engineering cultures. That correlation is not coincidental.

India needs that spark, too. We need children in Lucknow and Coimbatore to look up and think: “I could build that.” Because some of them will.

But all of this is much easier said than done.

4. Why India Hasn’t Built a Civil Aircraft Yet — The Hard Truths

Given all the strategic, economic, and cultural incentives, one might expect India to have built its own aircraft by now.

And yet, despite our early foray into aviation, our massive market, and our elite engineering talent, we have not done so.

The reasons behind this are not simple; they are structural, cumulative, and deeply revealing. Understanding why we failed is essential to understanding how we might finally succeed. And if you want to understand India’s aerospace struggles in microcosm, study the NAL Hansa.

A Small but Telling Success Story: The NAL Hansa

One bright spot in India’s civil aviation journey was the NAL Hansa, a two-seater light trainer developed in the 1990s by a government lab called NAL (National Aerospace Laboratory), in partnership with a Hosur-based private firm called Taneja Aerospace (TAAL).

It was, by every measure, a technically credible success: the country’s first all-composite civil aircraft, it achieved full certification and logged zero accidents across 2,000 flight hours. The engineering was sound. The design was elegant. The economics were compelling.

At roughly ₹3 crore per unit, it cost half the price of an imported Cessna aircraft, and was designed for flight schools, hobby aviators, and even coastal patrol. Here, finally, was proof that India could design and build a certified civil aircraft.

In 2021, an upgraded version called the Hansa-NG was released. It featured a glass cockpit, modern avionics, and a design so alluring that 75 flying clubs from around the country wrote letters of intent to procure units.

On paper, this looked like success. In reality, it exposed every systemic weakness in India’s aerospace ecosystem.

No Supply Chain, No Scale, No Sales

Although NAL and TAAL proved that they could design and certify a quality small aircraft, scaling from prototype to production proved impossible.

For starters, TAAL, the private manufacturer, had limited capacity and could not fund and market the entire operation by itself. Building aircraft is capital-intensive. You need tooling, facilities, working capital, and a sales force. TAAL had none of these at the scale required.

To compound this issue, there was a lack of Tier-1 systems integrators who wanted to step in. There was simply too much uncertainty.

Who would buy this aircraft, and would the number of sales justify the investment in the supply chain? After all, there was no national procurement plan in place. No guaranteed orders. No long-term commitment. Just hope and letters of intent—neither of which you can take to the bank.

Taking all this into account, a government committee eventually concluded the program had “no clear commercial use case.” And thus the Hansa program was quietly shelved.

This is where India’s story diverges sharply from every successful aerospace nation.

In Brazil, this is exactly where the state stepped in with the national decree that created Embraer. It was the same with COMAC in China, and Airbus in Europe.

They became national missions that had the backing of the state. Entrepreneurs and industrialists knew that they could invest in building out capacity to supply parts and components because the government had promised them orders. The state funded the aircraft, yes, but it also funded the entire ecosystem and guaranteed initial demand.

In India, nothing comparable happened.

We made a decision to run airlines, build airports, regulate flights, and import planes. But there was no equivalent to Decree-law 770 in Brazil that created Embraer or the megaproject classification of COMAC in China. Civil aircraft manufacturing was never elevated to a national priority. It remained a research project, not a strategic imperative.

For commercial aircraft manufacturing to exist, we need to engender a sense of national urgency in India’s science, technology, and industrial policy.

Meanwhile, HAL, which has the best shot at becoming a civil OEM, remains structurally embedded in defence procurement. Its operating model is optimized for license production of foreign technology, and does not risk heavy innovation. HAL is excellent at what it does—but what it does is assemble foreign designs under license, not develop indigenous commercial aircraft.

And unlike Embraer or COMAC, no civilian aviation company was ever spun out of HAL or scaled with state support to pursue commercial jet manufacturing.

The Hansa story is ultimately a story of half-measures. We proved we could engineer. We proved we could certify. But we never committed to actually building an industry.

We need to rally talent, capital, and institutional support to make this possible.

The Engine Bottleneck

But even if we do manage to get the financial and political backing, there are still some very hard technical barriers to overcome before we can begin to build cutting-edge aircraft.

The grandest of all these barriers is the jet engine.

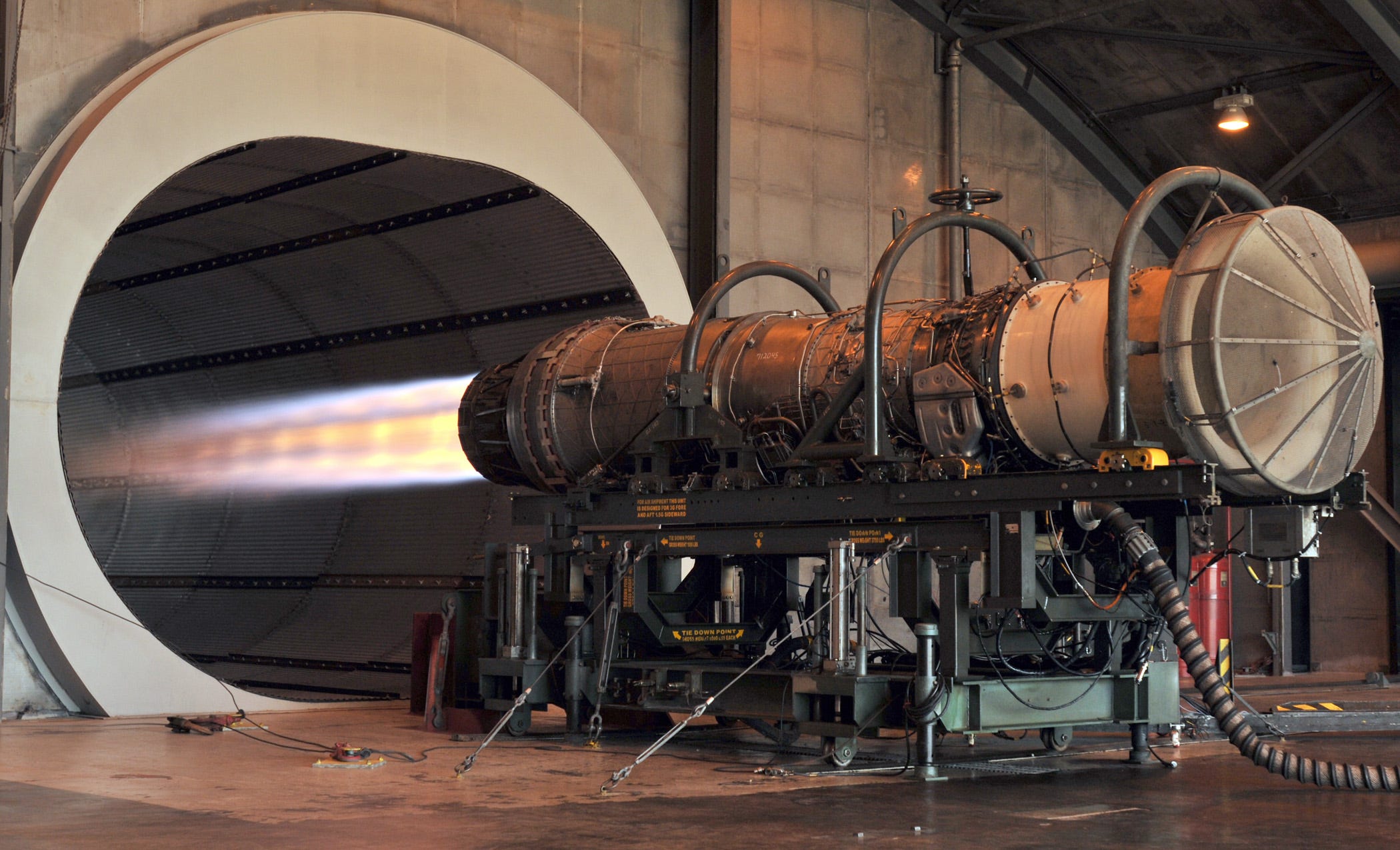

Modern civil airliners are defined by their engines: large, high-bypass turbofans that only a handful of nations on Earth can build: the US, UK, France, Russia, and now China (barely). These engines are marvels of engineering—spinning turbine blades at temperatures hotter than molten lava, tolerances measured in microns, materials that didn’t exist a generation ago.

India is yet to develop even a fighter jet engine. The Kaveri turbofan project, intended for the Tejas warplane, was launched in 1989 with the goal of producing an indigenous engine. Thirty-five years and billions of rupees later, it never achieved the required thrust-to-weight ratio and was eventually shelved.

To this day, India’s flagship fighter Tejas relies on American GE engines, while the HAL-manufactured Dornier 228 uses Garrett/Honeywell turboprops made abroad. Every advanced aircraft India operates—civilian or military—has a foreign heart.

This dependence has hamstrung projects like the Regional Transport Aircraft (RTA), a 70-90 seat turboprop airliner concept proposed in 2007. Because no Indian engine existed, NAL and HAL—the backers of the project—had to court Pratt & Whitney and GE to power the aircraft. The math was brutal: if the heart of your aircraft comes from Connecticut or Derby, you’re not building planes—you’re assembling someone else’s. But without engine control, cost and IP advantages evaporated, and the project landed dead on arrival.

This jet engine gap has been disincentivizing India from building a full civil aircraft for years. Any “100% Made in India” airliner would in reality be partially foreign, with the engine accounting for a major chunk of cost and IP. In a typical commercial aircraft, the engines represent 20-30% of the total cost and contain much of the most sophisticated technology.

Developing a world-class commercial engine would require billions of dollars, cutting-edge materials research, and long-term testing infrastructure. It would require mastering metallurgy, thermodynamics, computational fluid dynamics, and manufacturing processes that push the boundaries of what’s physically possible. This harsh reality dampened the case for an Indian airliner—why pour resources into an aircraft program if the soul of the airplane must be imported?

This is a sobering truth that we must face: without the ability to build engines, we will never lead in building aircraft. And building engines is one of the hardest problems in physics.

But “hardest” is not the same as impossible. And the gap between those two words is where countries are made.

A Deep-Rooted Financial and Cultural Risk Aversion

But even if we were to surmount the engine challenge, building a new commercial airplane would still be a risky business.

For India, the market and institutional risks loom just as large as the technical ones. Several reinforcing factors have created a culture of caution that deters big bets on civil aircraft.

For one thing, enormous upfront investments are required to develop a passenger plane from scratch. On top of that, you need decades of R&D. Airbus’s A380 program cost an estimated $25 billion before the first aircraft entered service. Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner development ran over $32 billion. These are investments that dwarf most companies’ entire market capitalizations.

There is a reason that the global civilian aircraft industry is an oligopoly: Airbus and Boeing have each had years go by when they spent tons of money and didn’t even ship a new product, but just climbed the learning curve. Boeing famously bet the entire company on the 707 in the 1950s—a decision that could have bankrupted them if it failed. It didn’t, and they became an aviation giant. But the risk was existential.

Seeing this, potential Indian entrepreneurial counterparts judged that entering a duopoly dominated by deep-pocketed giants (and increasingly challenged by state-backed entrants like COMAC) made little commercial sense. Private investors in India felt the same. Why risk billions on a 20-30 year payback when you could invest in software, pharmaceuticals, or consumer goods with faster returns and lower capital intensity?

This risk aversion wasn’t irrational—it was the logical response to India’s economic reality. For most of the post-independence era, capital was scarce, regulated, and expensive. Industrial licensing constrained what you could build. Foreign exchange controls limited imports of critical components and technology.

In such an environment, patient capital for decade-long aerospace bets simply didn’t exist. Investors wanted returns in years, not generations.

These factors created a self-fulfilling prophecy. Lacking bold investment, India never built a civil airliner—and because it never built one, investors and customers remained skeptical of the idea. The absence of success became evidence that success was impossible. The lack of examples became proof that examples couldn’t exist.

And so the dream remained just that: a dream.

5. Green Shoots, And A New Dawn

Despite this very sobering history, recent developments clearly suggest that India is trying to tilt the playing field and nurture a domestic aircraft industry in a meaningful way.

Tata Group’s recent joint venture with Airbus to manufacture military transport planes in India is one example of a major leap forward that could do wonders for the local supply chain.

As part of this deal, the Indian government placed an order for 56 Airbus C295 aircraft, with 40 of them to be built in India by Tata Advanced Systems.

With a brand-new final assembly line in Vadodara, this will be the first time that a full passenger-capable aircraft will be assembled by an Indian private company.

Over 13,400 parts of the C295 are being sourced from 125+ Indian suppliers across seven states, and Tata’s facility is slated to deliver the first Made-in-India C295 by 2026, reaching an annual capacity of 8 aircraft thereafter.

In the words of Prime Minister Modi, change is coming:

The transport aircraft made here will give power to our Army and create a new ecosystem of aircraft manufacturing...I also see the days coming when larger passenger planes for the world will also be made in India.

Mirroring the strong statements and encouraging recent moves by the public sector, private sector companies have also stepped up to the task, including several startups.

For instance, Delhi-based DG Propulsion is developing compact jet engines for drones and future aircraft. It has successfully built the DG J40 micro-turbojet (40 kgf thrust) for UAVs and defence applications and even ran it in hour-long endurance tests. Next, they are setting their sights on a larger indigenous turbofan engine that they hope to complete in 2–3 years.

Younger startups such as Parsec Aerospace and HyPrix are also taking aim at the engine problem, working on reaction engine designs including gas turbines and ramjets. If these efforts succeed, they could fundamentally reduce our reliance on foreign technologies.

The most well-funded and noteworthy startup building in the aviation space is LAT Aerospace, founded by Surobhi Das and Deepinder Goyal of Eternal. They are building India’s first hybrid-electric aircraft, based out of a 50,000 square foot R&D facility in Gurgaon.

Their vision is to begin with eight-seater aircraft that can take off and land on short runways, ideal for small airports that can be easily stood up to boost regional connectivity.

Along with these startups, several established Indian firms have also been expanding their ambitions.

Notable among them is Bengaluru-based Dynamatic Technologies, a global Tier-1 supplier of critical airframe components for firms like Boeing and Airbus. This company manufactures the flap-track beam assemblies for Airbus’s A320 family, and it recently won a contract to produce every door variant for Airbus’s A220 airliner – the largest such work package Airbus has placed in India.

Similarly, Godrej & Boyce is an iconic Indian company with deep manufacturing capability. They have partnered with the Indian government and ISRO to work on the Kaveri engine and rocket thrusters, and recently closed a deal with Pratt & Whitney to manufacture aircraft engine components in India.

In summary, there is real momentum building. But this movement needs a bigger push. We must have more conviction that commercial aircraft manufacturing is a problem worth working on full-time, not just as a side project or research thesis but as a national mission built by private risk.

And that’s where my story begins.

6. When The Past Recedes And The Future Opens

Growing up, I was obsessed with science and technology. I spent many nights poring over literature related to the Apollo mission, Concorde, and Lockheed Martin’s fabled aerospace division.

Although I wanted to be part of these stories with every fibre of my being, I never felt like it was a viable option for me. Like many other kids in India, I was under the impression that academia was the only path to ascend this particular mountain, and I didn’t fancy the prospect of spending decades studying.

The kind of engineering work that excited me seemed so far away.

Until everything changed one day in January 2022. While solving a Rubik’s cube in my seat on the flight back from Hyderabad to my hometown of Lucknow (which you could fairly characterise as one level above rawdogging a plane ride), I was interrupted by a tap on my shoulder.

I turned to see a kindly lady smiling and pointing at the book that lay on my lap - Black Holes: A Lecture series by Stephen Hawking. She recounted how her son had once bought the same book, and she began to tell me more about him.

It turned out that her son and his two friends were the cofounders of Kalam Labs, a Y Combinator and Lightspeed-backed startup that manufactures high-altitude aircraft designed to collect weather data from the edge of space.

I almost spat out my water when I heard that this ambitious aerospace work was happening in an office just a hundred meters from my school. Yes, you heard that right. Aerospace innovation. In LUCKNOW. Obviously, I had to get in on this action.

Just two days later, I found myself in the Kalam Labs office for an interview, and I continued to go there every day after school for the next 6 months. For the first time in my life, it hit me that maybe I could build my own airplanes and spacecraft someday.

As time passed, I began to internalize this message more and more: the greatest monuments of mankind are built by those who can live with delusion long enough for it to become a reality.

And so I decided to go to University of Alberta the same year to pursue Computer Science with a minor in Physics. Side note: A funny glitch on my transcript still says I minored in Polish. I’ve never taken a Polish course in my life.

The reason I chose this path was because the University of Alberta was home to the father of Reinforcement Learning, Richard Sutton. I knew that computational intelligence would be a key part of aviation going forward, so I thought it would be a good idea to learn my trade from the master, while also keeping my passion for physics alive on the side.

In Alberta, I joined the university’s autonomous drone club, working on fixed-wing and multirotor aircraft that competed across Canada and the U.S. I also had a chance to spend a summer semester at Stanford and imbibe the energy of Silicon Valley.

Near the end of my Stanford semester, I was seriously debating whether to go back to India or stay in North America. Although I loved the education I was getting, I had seen enough exciting aviation efforts in places like Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Chennai that I felt pulled to come back.

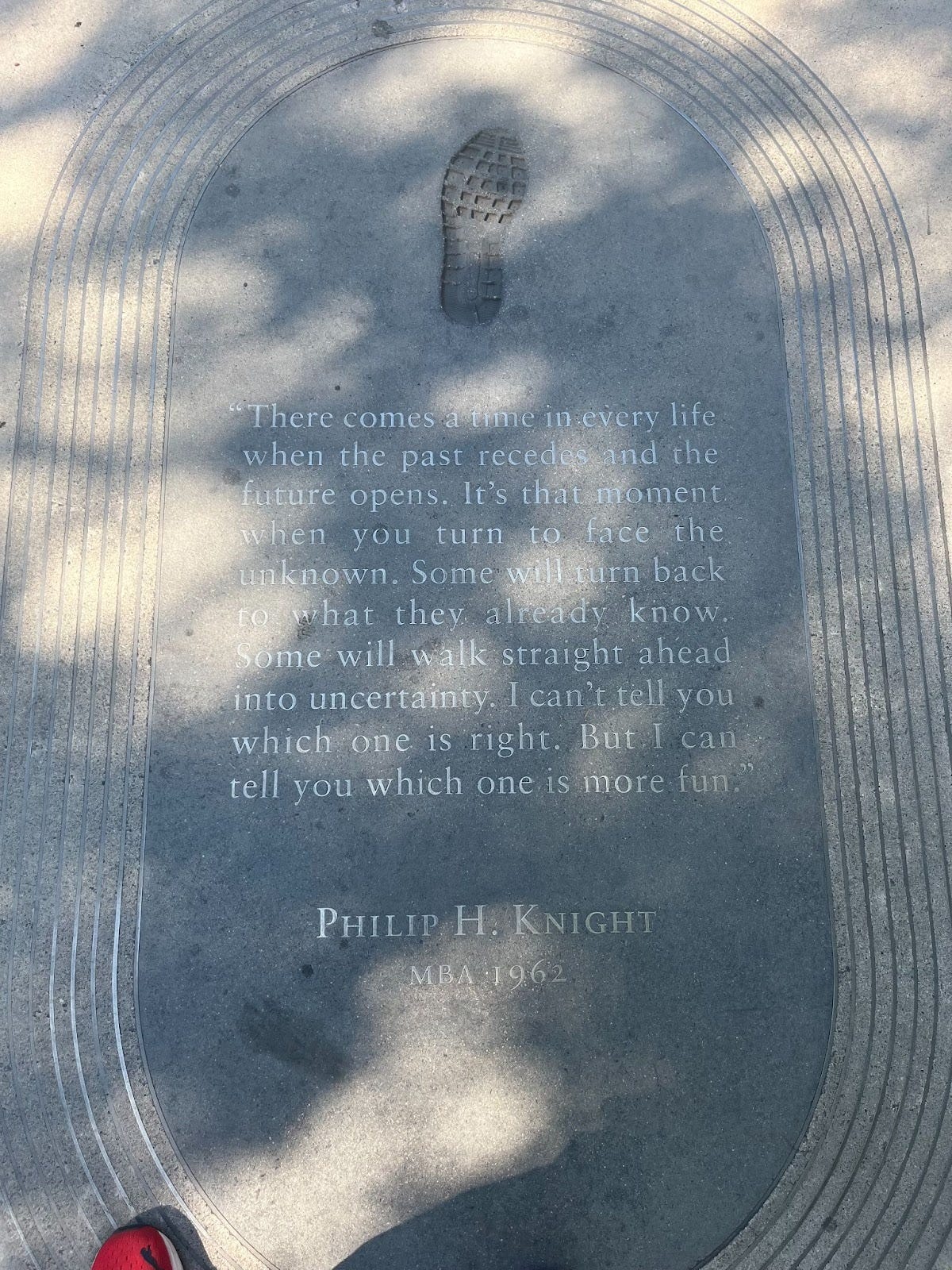

One day, while walking back to my dorm, I saw a quote etched into the concrete on one of the busiest roads on campus:

This was one of those seemingly cliché moments in which it feels like the universe is asking you to do something. So who was I to refuse?

I decided to take a gap semester and move to Bangalore for the very first time. But it would probably be more accurate to call it a break rather than a gap since I never went back.

These unpublished scratchings from my college-era blog probably give you an idea of what was occupying my mind instead:

A man was able to set foot on the moon for the first time in history in 1969.

In 1969, 96% of US telephones still had dials. The microwave oven wasn’t in half of US homes until 1986. The handheld calculator, the Sony Walkman, the VCR, and the cordless phone didn’t hit until the early 1980s. But America was on the moon. Let that sink in.

The space suits of the two Apollo 11 astronauts were assembled by hand. Their parachutes were cut and sewn by hand. Apollo’s two onboard computers had hardware programs instead of software. Their wires and tiny metal rings were woven by hand with absolute precision to create the 0s and 1s. The sheer dedication of hundreds of thousands of people to accomplish a goal so brave blows my mind.

We don’t know what the future will look like but I have a clear idea of what I want it to look like with infinite clean energy, extremely fast air travel, multi-planetary space flights for the public, connecting every corner of the world, and so much more. This is why I believe that it is very important for everyone to work on problems that are valuable for the future.

Long story short, I moved to Bangalore in May 2024 after receiving a grant from Emergent Ventures. Side note: A massive shoutout to Shruti and the EV team for taking a leap of faith in me and 100s of other kids with big dreams and small pockets. We wouldn’t be here without you :)

My objective in Bangalore was to truly understand the ecosystem that currently exists in India for aviation, space, and manufacturing.

I spent months talking to anyone who’s ever tried to build an airplane in India - Taneja aerospace, L&T Aerospace, Tata Group, and Valeth High Composites.

I learned a lot about how the supply chain for aircraft manufacturing is developing, how regulators think, and how we might finally have a shot at making big things happen.

At the same time, I got to work with Rahul Seth of industrial47 (big shoutout to Rahul!), which opened the door for me to meet companies like Pixxel Space (read the awesome Tigerfeathers profile of them here), Airbound (also covered by Tigerfeathers), Ethereal Machines, HyPrix Aviation, and many more.

The first time I visited Pixxel’s spacecraft facility in Bangalore, I was stunned.

Right in front of me, in India, was a company building and launching cutting edge satellites! As I heard from the founders Awais and Kshitij the story of how they started Pixxel while still in college, I knew that I needed to work with this team.

Later that day, I texted Awais and told him that I wanted to understand how he operated. He quickly set up an arrangement for me to shadow him at the Pixxel office. I could not have asked for a better opportunity (biggest shoutout to Awais for this!).

After a couple months of shadowing him, speaking to the amazing team at Pixxel, understanding the government’s outlook for audacious, young startups, and learning everything I could about the manufacturing bottlenecks in India, I decided to build my own dream.

Per Aspera Ad Astra

In June 2025, I founded a company called Aspera Industries with the intention of making an end-to-end OEM that could manufacture airplanes in India.

We want to make India the next aviation capital of the world, and manufacturing full-scale airplanes is a major step forward in this mission.

Just like Embraer began with the vision of dominating the small niche of regional passenger aircraft, we have set out to dominate the market for medium sized autonomous, amphibious airplanes.

Amphibious means that the aircraft will be capable of taking off and landing from both water and land. Autonomous means that there will be no pilot on board. At first, these airplanes will only be used for cargo transport purposes to prove that we can build safe, reliable aircraft.

We are starting with seaplanes because water runways can be licensed and operated with simpler infrastructure than many land aerodromes. Several countries already run formal frameworks for seaplane platforms and water aerodromes, making it easier to stand up routes fast while meeting safety requirements.

Besides the increased ease of taking off and landing on water, there is another simple reason that regulations are far more forgiving when it comes to seaplanes rather than conventional airplanes. Flying over civilian airspace and property creates huge regulatory and national security risks. In contrast, flying over empty swathes of ocean has much less potential for things to go wrong.

Therefore, we will begin with seaplanes aimed at middle-mile logistics: connecting warehouses and ports that are separated by ocean.

Our initial geographies of interest are the Indian subcontinent, South East Asia, and the Middle East. Countries like the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Singapore, and Indonesia already operate sizable seaplane ecosystems or boat-based transfers, showing clear regulatory and operational precedent that we can build on for cargo missions.

The game plan is simple: start on water, own the middle mile, prove reliability and unit economics, then expand to land with the same autonomy stack and a growing range of airframes. At end stage, we plan to make passenger aircraft that can carry out any mission. It will take a while to get to that stage, but luckily…

All things said, Aspera has set out to build the greatest aircraft company from India for the world. To do that, we must marshal capital and attract great talent that wants to do their best work. But first we must believe.

You might find this delusional. Almost comically naive. You’re not wrong. But the entire aerospace industry started with the delusion of making gigantic aluminium tubes carrying 300 people flying at 800 km/hr.

The Wright brothers were literally bicycle mechanics who thought they could fly. The legendary Soviet rocket engineer Sergei Korolev was at one point just a babbling gulag prisoner who talked of reaching the stars.

So why shouldn’t we? If we don’t believe, nothing will change.

But if we all believe it, if 1.4 billion Indians come together to share our delusion, then India can certainly become the aerospace capital of the world.

And that is the future that we must open. So come join us.

To Khushi: thank you for stepping up to the podium this week and sharing your enthusiasm and insights with us. To our readers - please feel free to share your appreciation for Khushi’s work either in the comments below or via her Twitter/LinkedIn.

The Tigerfeathers Spotlight Series continues over the next couple of weeks. If you’re keen to throw your name in the hat or you have suggestions for future contributors, hit us up. Until then, keep your Tiger eyes sharp and your Tiger feathers sharp-er (or whatever).

And, as always, if you made it all the way here and you thought this was a good use of your time, it would mean a lot to us if you took a couple of seconds to share this post.

Someone said:

Be delusional enough to believe you can & be disciplined enough to prove it. That's how you win.

Bon voyage, Khushi! 🎉